READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORTIn this article, we aim to expand your thinking about the cost of materials to account for the costs borne by individuals and fenceline communities who are exposed to toxic chemicals every day. The bottom line is that some products can be sold cheaply because someone else is carrying the burden of the true cost.

Where We Are

When you shop for a flooring product, what do you consider? Perhaps you think about the look and feel of the product and its durability. You likely also consider the price. The cost of using a material is influenced by the cost to purchase the product itself, the installation cost, maintenance costs, as well as how long the product will last (when you will have to pay to replace it). These are all internalized costs, paid by the building owner.

These costs alone, however, do not consider the full impacts of materials along their life cycles. More and more building industry professionals are paying attention to the content of building products and working to avoid hazardous chemicals in an effort to help protect building occupants and installers from health impacts following chemical exposures. To understand the true, full cost of a product, we must look beyond just the monetary cost of purchasing and maintaining a product.

Hidden Costs

Many of the costs associated with products are more or less hidden when choosing a building material. Just a few of these hidden costs are outlined below.

- Toxic Chemical Impacts on Human Health: This includes direct medical expenses due to diseases caused or exacerbated by chemical exposures, as well as indirect health-related costs like loss of productivity in work or school and decreased economic productivity in terms of loss of years of life and loss of IQ points. It also includes the immeasurable costs to quality of life and loss of loved ones.

- Environmental Contamination Costs: Contamination of the environment with toxic chemicals contributes to the human health impacts noted above. In addition, the costs of environmental contamination can include reduced property values in and around contaminated areas, loss of income and food production from the contamination of farms, and the cost of clean up activities (e.g. utilities clean up of water contamination). Less quantifiable costs include damage to wildlife and ecosystems.

- Climate Change Impacts: Production of chemicals and products is often energy-intensive and based on fossil fuels. Most products contribute to climate change to some extent. Some contribute more than others because of energy use or the release of chemicals with high global warming potential. These greenhouse gas emissions exacerbate climate change, leading to increasingly powerful storms and fires, with increasingly high and recurring costs for recovery. Climate change also magnifies the impacts of toxic chemicals, increasing the human and environmental health costs.

- Environmental Injustice: Disproportionately, the health impacts and associated costs throughout the life cycle of products (e.g. during manufacturing and at end of life) fall on communities of color and low-income communities. The numerical cost of these impacts may not be quantifiable, but the costs to our society are no less clear as a result.

Some Numbers

Quantifying the estimated costs of these impacts is challenging. In most cases, there is just not enough data to estimate the full costs of hazardous chemical impacts. Below are examples of estimated direct and indirect costs of some toxic chemicals to society.

Toxic Chemical Impacts on Human Health

The US Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA) estimates that American workers alone suffer more than 190,000 illnesses and 50,000 deaths per year that are related to chemical exposures. These chemical exposures are tied to cancers, as well as other lung, kidney, heart, stomach, brain, and reproductive diseases.1

While some workers may see greater exposures to hazardous chemicals, all of us are impacted. Many of you are likely familiar with PFAS, aka per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. PFAS have been used in a wide range of applications, including stain-repellent treatments for carpet and countertop sealers. The widespread use of PFAS has led to extensive contamination of the planet and people. Increasing research and attention to this group of chemicals has led to some quantitative understanding of the costs to society of their use. A recent publication in Environmental Science and Technology outlined some of the true costs of PFAS chemicals. The authors highlight that, “A recent analysis of impacts from PFAS exposure in Europe identified annual direct healthcare expenditures at €52–84 billion. Equivalent health-related costs for the United States, accounting for population size and exchange rate differences, would be $37–59 billion annually.” Importantly, they further call out the fact that, “These costs are not paid by the polluter; they are borne by ordinary people, health care providers, and taxpayers.”2

And this is just the cost of one group of chemicals. Another recent study estimated the cost of US exposures to phthalates, a group of chemicals used to make plastics more flexible, to be approximately $40 billion or more due to loss of economic activity from premature deaths.3 While more research is needed, the scale of these estimated costs is staggering.

Environmental Contamination Costs

The release of PFAS chemicals has contaminated water supplies globally. About two-thirds of the US population receives municipal drinking water that is contaminated with PFAS. Reducing the levels of PFAS in drinking water can be expensive, and none of the methods fully remove PFAS. In the Environmental Science and Technology study mentioned above, the authors note that “following extensive contamination by a PFAS manufacturer in the Cape Fear River watershed, Brunswick County, North Carolina is spending $167.3 million on a reverse osmosis plant and the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority spent $46 million on granular activated carbon filters, with recurring annual costs of $2.9 million. Orange County, California estimates that the infrastructure needed to lower the levels of PFAS in its drinking water to the state’s recommended levels will cost at least $1 billion.” Again, these costs are typically not paid by the polluter but shifted to the public.4

Climate Change Impacts

Chemicals used in the production of some PFAS are ozone depleters and potent greenhouse gases. New research released in September by Toxic-Free Future, Safer Chemicals Healthy Families, and Mind the Store ties the release of one such chemical, HCFC-22, to the production of PFAS used in food packaging. The reported releases of this one chemical from a single facility is equivalent to “emissions from driving 125,000 passenger cars for a year.”5

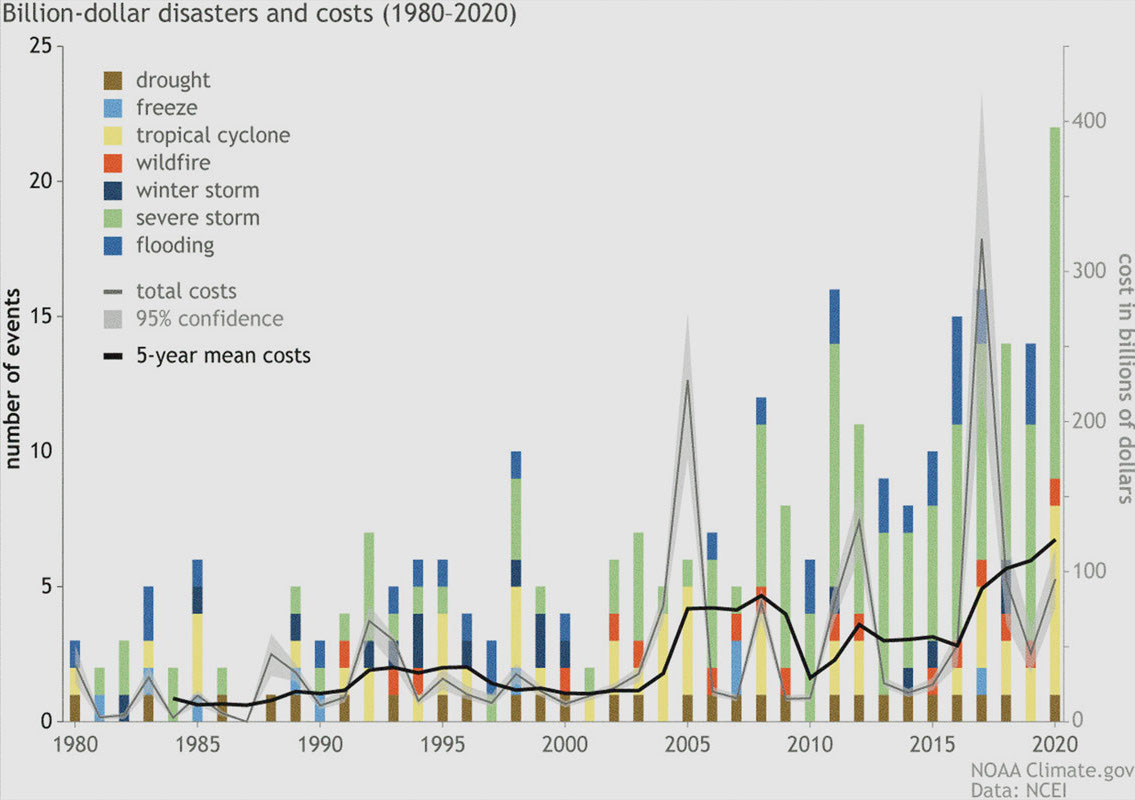

The costs of climate change impacts are immense. For example, the number of billion-dollar disasters and the total cost of damages due to natural disasters have been skyrocketing. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration describes how climate change contributes to increasing frequency of some extreme weather events with billion-dollar impacts. They outline the broader context of these extreme weather events saying that, “the total cost of U.S. billion-dollar disasters over the last 5 years (2016-2020) exceeds $600 billion, with a 5-year annual cost average of $121.3 billion, both of which are new records. The U.S. billion-dollar disaster damage costs over the last 10-years (2011-2020) were also historically large: at least $890 billion from 135 separate billion-dollar events. Moreover, the losses over the most recent 15 years (2006-2020) are $1.036 trillion in damages from 173 separate billion-dollar disaster events.”6

Figure 1. Billion-dollar Disasters and Costs (1980-2020)7

Environmental Injustice

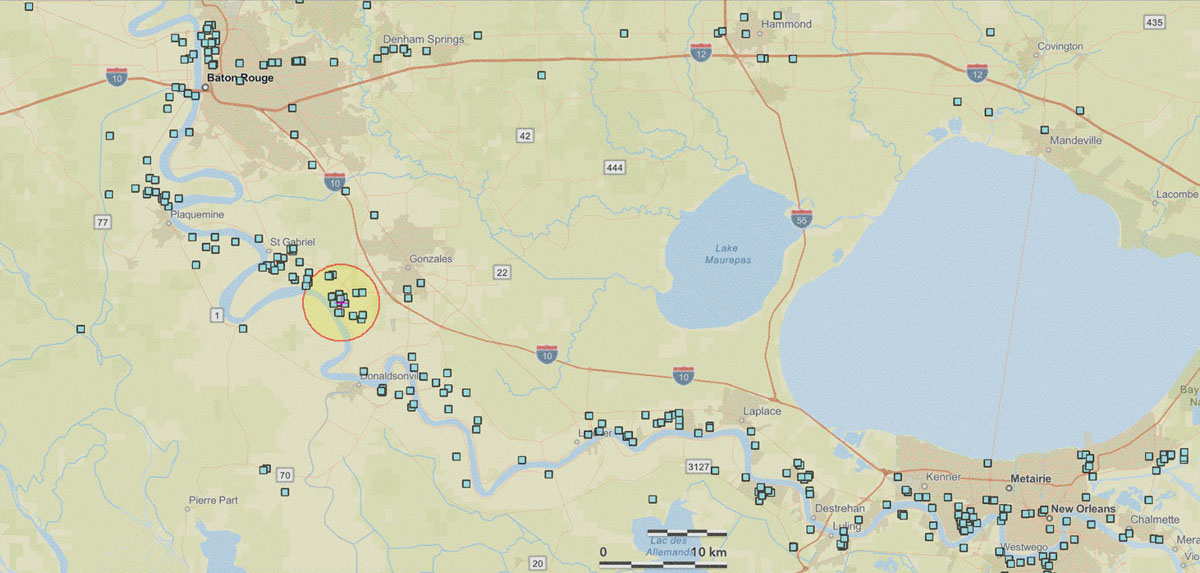

In the US, communities of color and low-income communities are disproportionately impacted by environmental pollutants.8 These communities often face hazardous releases from multiple sources due to high concentrations of manufacturing facilities near their homes. The area along the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge is known as “Cancer Alley” because of the concentration of industrial activity and the associated elevated cancer risks.9 Figure 2 maps facilities that report to EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) in this area. These are facilities that release or manage hazardous chemicals that require reporting to EPA.

The city of Geismar, LA is home to 18 TRI facilities. These facilities reported a total of over 15 million pounds of on-site releases of hazardous chemicals to air, water, and land in 2019.10 Several of these facilities produce chemicals used in the building product supply chain. Two facilities produce chlorine for internal or external production of PVC, which can be used to make pipes, siding, windows, flooring, and other building products.11 Two other facilities manufacture a key ingredient of spray foam insulation, MDI. Some of these facilities have a history of noncompliance with EPA regulations, one having significant violations for eight of the last twelve quarters and another having significant violations for all twelve of the last twelve quarters.12 Surrounding communities are impacted by regular toxic releases from these facilities and are vulnerable to accidents involving toxic chemicals. For example, an explosion and fire at the vinyl plant in 2012 released thousands of pounds of toxic chemicals, led to a community shelter in place order, and shut down roads and a section of the Mississippi River.13

More than 5,000 people live within three miles of one or more of these four facilities. This community is disproportionately Black — 35% of the population compared to 12% in the US overall. Thirty percent of the population is children, with about 1500 kids under the age of 18. This community has a higher estimated risk of cancer from toxics in the air than most places in the US — almost four times the national average.14

Where we go from here?

The message we hope you take away from this article is that we must move beyond discussions based purely on the material costs or up-front costs of products. We must all work together to acknowledge and shed light on the true costs that toxic chemicals have within our society and on specific communities. The impacts of hazardous chemicals are, of course, not just monetary –people’s lives are significantly impacted in multiple ways. The current system subsidizes cheap products by robbing individuals of the opportunity for healthy lives and for children to play, and grow up, and enjoy a full and normal life.

Unfortunately, there is not currently enough information available to make detailed cost accounting broadly possible, and no framework exists for accounting for and comparing the full extent of product costs. Transparency about what is in a product, how the product is made, and hazardous emissions – beyond those required to be reported by law – is critical. Programs that place extended responsibility on manufacturers to manage materials at their end of life (as part of extended producer responsibility or EPR)15 can be a starting point for conversations about the full life cycle impacts of products and can help hold manufacturers accountable for a broader array of costs, once they are better understood.

In the meantime, Habitable works to incorporate a life cycle chemical perspective into our safer material recommendations like our Informed™ product guidance and Pharos database. These tools are a work in progress initially focused on avoiding hazardous chemicals in a product’s content. As a starting point, this helps protect not only building occupants and installers, but also others impacted by those hazardous chemicals throughout the supply chain. When hazardous chemicals are used, it is likely that someone throughout the supply chain is impacted. Informed™ can help you choose safer building products based on the information that we have today as we work to expand our incorporation of life cycle chemical impacts into our research and to provide guidance on a broader range of materials.

Habitable looks forward to continuing to identify and provide the critical data needed to assist in decision making with a more comprehensive view of the true costs of materials, and to developing resources to help communicate the collective return on investment seen by a society where all people and the planet thrive.

SOURCES

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. “Transitioning to Safer Chemicals: A Toolkit for Employers and Workers.” Accessed October 21, 2021. https://www.osha.gov/safer-chemicals.

- Cordner, Alissa, Gretta Goldenman, Linda S. Birnbaum, Phil Brown, Mark F. Miller, Rosie Mueller, Sharyle Patton, Derrick H. Salvatore, and Leonardo Trasande. “The True Cost of PFAS and the Benefits of Acting Now.” Environmental Science & Technology 55, no. 14 (July 20, 2021): 9630–33. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c03565.The original study’s authors note that because data is only available for a few health endpoints and that these costs are likely a minimum health-related cost. See: Goldenman, Gretta, Meena Fernandes, Michael Holland, Tugce Tugran, Amanda Nordin, Cindy Schoumacher, and Alicia McNeill. “The Cost of Inaction : A Socioeconomic Analysis of Environmental and Health Impacts Linked to Exposure to PFAS.” Nordisk Ministerråd, 2019. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:norden:org:diva-5514.

- Trasande, Leonardo, Buyun Liu, and Wei Bao. “Phthalates and Attributable Mortality: A Population-Based Longitudinal Cohort Study and Cost Analysis.” Environmental Pollution, October 12, 2021, 118021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118021.; Guzman, Joseph. “Shocking Study Says Chemicals Found in Shampoo, Makeup May Kill 100k Americans Prematurely Each Year.” The Hill, October 12, 2021. https://thehill.com/changing-america/well-being/576436-shocking-study-says-chemicals-found-in-shampoo-and-makeup-may.

- Cordner, Alissa, Gretta Goldenman, Linda S. Birnbaum, Phil Brown, Mark F. Miller, Rosie Mueller, Sharyle Patton, Derrick H. Salvatore, and Leonardo Trasande. “Correction to The True Cost of PFAS and the Benefits of Acting Now.” Environmental Science & Technology 55, no. 18 (September 21, 2021): 12739–12739. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c04938.

- Schreder, Erika, and Beth Kemler. “Path of Toxic Pollution.” Toxic-Free Future, Safer Chemicals Healthy Families, and Mind the Store, September 2021. https://toxicfreefuture.org/daikin-path-of-toxic-pollution.

- Smith, Adam B. “2020 U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters in Historical Context.” NOAA Climate.gov, January 8, 2021. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2020-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters-historical.

- Smith, Adam B. “2020 U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters in Historical Context.” NOAA Climate.gov, January 8, 2021. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2020-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters-historical.

- Bell Michelle L. and Ebisu Keita, “Environmental Inequality in Exposures to Airborne Particulate Matter Components in the United States,” Environmental Health Perspectives 120, no. 12 (December 1, 2012): 1699–1704, https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1205201; Michael Gochfeld and Joanna Burger, “Disproportionate Exposures in Environmental Justice and Other Populations: The Importance of Outliers,” American Journal of Public Health 101, no. Suppl 1 (December 2011): S53–63, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300121; “Volume 1: Workgroup Report to Administrator,” Environmental Equality: Reducing Risk for All Communities (United States Environmental Protection Agency, June 1992), https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-02/documents/reducing_risk_com_vol1.pdf.

- Tristan Baurick, Lylla Younes, and Joan Meiners, “Welcome to ‘Cancer Alley,’ Where Toxic Air Is About to Get Worse,” ProPublica, October 30, 2019, https://www.propublica.org/article/welcome-to-cancer-alley-where-toxic-air-is-about-to-get-worse; James Pasley, “Inside Louisiana’s Horrifying ‘Cancer Alley,’ an 85-Mile Stretch of Pollution and Environmental Racism That’s Now Dealing with Some of the Highest Coronavirus Death Rates in the Country,” Business Insider, April 9, 2020, https://www.businessinsider.com/louisiana-cancer-alley-photos-oil-refineries-chemicals-pollution-2019-11.

- Data collected from US EPA’s TRI database by searching by city: https://www.epa.gov/toxics-release-inventory-tri-program.

- Vallette, Jim. “Chlorine and Building Materials: A Global Inventory of Production Technologies, Markets, and Pollution – Phase 1: Africa, The Americas, and Europe.” Healthy Building Network, July 2018. https://habitablefuture.org/resources/chlorine-building-materials-project-phase-1-africa-the-americas-and-europe/.

- ECHO. “Detailed Facility Report: BASF Corp.” Data & Tools. Accessed October 21, 2021. https://echo.epa.gov/detailed-facility-report?fid=110000597364.; ECHO. “Detailed Facility Report: Occidental Chemical Corporation.” Data & Tools. Accessed October 21, 2021. https://echo.epa.gov/detailed-facility-report?fid=110000449774.; ECHO. “Detailed Facility Report: Rubicon LLC.” Data & Tools. Accessed October 21, 2021. https://echo.epa.gov/detailed-facility-report?fid=110000597373.; ECHO. “Detailed Facility Report: Westlake Vinyls Co.” Data & Tools. Accessed October 21, 2021. https://echo.epa.gov/detailed-facility-report?fid=110000746328.

- Schade, Mike. “(Yet) Another PVC Plant Explosion and Fire.” Center for Health, Environment & Justice (CHEJ), 2012. http://chej.org/2012/04/16/yet-another-pvc-plant-explosion-and-fire.

- Data is from US EPA’s EJScreen: https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper. Population and demographic information is based on a 3-mile radius around the four facilities combined – Rubicon, Occidental Chemical, BASF, and Westlake Vinyls (location based on latitude and longitude per the Toxic Release Inventory). NATA Air Toxics Cancer Risk is in the 95-100th percentile for the United States.

- OECD defines Extended Producer Responsibility as “a concept where manufacturers and importers of products should bear a significant degree of responsibility for the environmental impacts of their products throughout the product life-cycle, including upstream impacts inherent in the selection of materials for the products, impacts from manufacturers’ production process itself, and downstream impacts from the use and disposal of the products.” See: OECD. “Fact Sheet: Extended Producer Responsibility.” Accessed October 21, 2021. https://www.oecd.org/env/waste/factsheetextendedproducerresponsibility.htm.

My daughter is nine, and she is going through the first stages of puberty.

This is four years before I reached that stage and two years before any of my three sisters or sister-in-law hit this developmental milestone. While nine is still considered in the normal developmental range for girls in the United States, it is certainly early compared to the women in my generation.

As HBN’s Chief Research Officer, it is my job to understand the impacts that different chemicals can have on human health and work every day to help people make informed decisions about the products they use. As a mother, it is also my job to keep my kids safe. While my research will not help me answer the question about why my daughter may be going through puberty earlier than I did, I can share what I have learned about chemicals found in building materials and their potential impacts on children’s health in the hope that you can join me in making the best decisions we can for our future generations.

While this article will focus on one environmental factor (exposure to pollutants related to the use of building products), I recognize this is one of many factors that impact children’s health. These include biological factors (e.g. sex, genetics, age), social factors (e.g. income, culture), and environmental factors (e.g. diet, exposure to pollutants).1 With this in mind, this article does not tie specific products or chemicals to specific health outcomes in children. Instead, this article discusses two groups (or classes) of chemicals used in building products that are known to have reproductive toxicity or endocrine disrupting concerns and are found both in household dust and children’s bodies.

Children are not little adults. For example, my five year old likes to sleep in a small cardboard box at night these days with his neck at an angle that would take me weeks to uncrick. They also eat more, inhale more, and drink more than adults per kilogram body weight.2 They also spend more time on the floor (see box story above) and are therefore more likely to ingest or inhale household dust. Their immune and metabolic systems are not fully developed, so their bodies process and eliminate chemicals differently than adults. Lastly, children’s bodies are in a constant state of growth and development, and as such they can be more sensitive to chemicals than adults.3

Let’s explore two groups of chemicals found in building products and in children’s bodies that can impact the endocrine systems.

Bisphenols

Bisphenols are a group of chemicals including bisphenol A (BPA) and bisphenol S (BPS). BPA is on the EU Substances of Very High Concern (SVHC) list due to endocrine disrupting properties. Specifically, many bisphenols mimic the hormone estrogen. BPA is considered “Toxic to Reproduction” by the European Chemicals Agency. Bisphenols are found in many different types of products including plastic items, paper receipts, and metal food and beverage can liners. In building products, BPA-related compounds are found in “epoxy” resin products, for example, epoxy flooring adhesive and epoxy fluid-applied flooring.

In last year’s article, “There’s What In My Body?” I shared how I found BPA and BPS in my body through a biomonitoring study by Silent Spring. Compared to other participants in the study, I had lower levels of BPA but higher levels of BPS, a common replacement for BPA. I was surprised and disturbed by the results, and I cannot help but wonder what my daughter’s levels would be today if we tested for bisphenols or any of the other endocrine disrupting compounds found in household products. Levels of BPA in children are typically higher than for adults. Most importantly, even tiny amounts of endocrine disrupting chemicals, including BPA, can lead to health and behavioral problems in developing children.4 For example, increasing urinary BPA levels in children are linked to an increase in behavioral regulation problems, anxiety, and hyperactivity.

The good news is that bisphenols are rapidly metabolized. If you can identify and remove sources of bisphenols from your home and diet, you can reduce your exposure.

Orthophthalates

Orthophthalates are a group of chemicals used as plasticizers – additives that make plastics more flexible. Orthophthalates can be developmental toxicants per the U.S. National Toxicology Program.5 Some common orthophthalates interfere with the production of testosterone, which can have irreversible effects on the male reproductive system. Higher exposure to certain orthophthalates has been associated with higher incidences of preterm birth; in particular, mothers who had consistently higher exposures to orthophthalates were five times more likely to experience spontaneous preterm birth (Ferguson et al 2014, JAMA Pediatrics). Preterm birth is associated with a variety of adverse health outcomes including increase in disability as young adults.6

Orthophthalates are sometimes called “everywhere chemicals” because they are so common in household products. With respect to building products, up until recently orthophthalates were prevalent in vinyl flooring. While the vinyl flooring industry has largely phased them out of new products, many homes with vinyl flooring installed before 2015 will still likely contain orthophthalate plasticizers. Orthophthalates can also be found in sealants used throughout the home. While the sealant industry is beginning to phase out these chemicals, they are still commonly used.

Similar to bisphenols, phthalates are metabolized quickly, so identifying potential sources and removing those from the home is the easiest way to reduce exposure. Possible sources include older plastic toys, cleaning products, personal care products, sealants, older vinyl flooring (pre-2018), and fragrances.

My daughter is not an outlier. Over the last 40 years, the average age of initial onset of puberty has decreased by 12 months. There are likely multiple reasons for this trend. However, an increase in exposure to a cocktail of endocrine disruptors is a possible explanation. Collectively, we can use our voices and buying power to shift the market towards safer products.

What can you do to help?

- You can step up out of red and choose products that are ranked ideally yellow or green through Informed™

- Ask your retailer to keep products containing hazardous chemicals off of the shelves. The Mind the Store campaign by Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families encourages retailers to move away from phthalates, bisphenols, and other hazardous chemicals. Hot off of the presses is the latest Retailer Report Card. See how your favorite retailer stacks up.

- Support legislation that uses the class-based approach to ban problematic chemicals. The Green Science Policy Institute develops research and supports policies that prevent the use of “Six Classes of Harmful Chemicals”. By reducing the use of entire classes of chemicals, we reduce the chance for regrettable substitution and the inefficiencies and dangers associated with a one-at-a-time or “toxic whack-a-mole” approach to chemical restrictions. In addition to bisphenols and phthalates, GSPI’s Six Classes include per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS), antimicrobials, flame retardants, some solvents, and certain metals. Numerous state legislatures have passed laws restricting the use of bisphenols and phthalates in a variety of products.

SOURCES

- Commission and for Environmental Cooperation. “Toxic Chemicals and Children’s Health in North America: A Call for Efforts to Determine the Sources, Levels of Exposure, and Risks That Industrial Chemicals Pose to Children’s Health,” 2006. http://www3.cec.org/islandora/en/item/2280-toxic-chemicals-and-childrens-health-in-north-america-en.pdf.

- Miller, Mark D., Melanie A. Marty, Amy Arcus, Joseph Brown, David Morry, and Martha Sandy. “Differences between Children and Adults: Implications for Risk Assessment at California EPA.” International Journal of Toxicology 21, no. 5 (October 2002): 403–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10915810290096630.

- Commission and for Environmental Cooperation. “Toxic Chemicals and Children’s Health in North America: A Call for Efforts to Determine the Sources, Levels of Exposure, and Risks That Industrial Chemicals Pose to Children’s Health,” 2006. http://www3.cec.org/islandora/en/item/2280-toxic-chemicals-and-childrens-health-in-north-america-en.pdf.

- Braun, Joe M., and Russ Hauser. “Bisphenol A and Children’s Health.” Current Opinion in Pediatrics 23, no. 2 (April 2011): 233–39. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283445675.

Braun, Joe M., Amy E. Kalkbrenner, Antonia M. Calafat, Kimberly Yolton, Xiaoyun Ye, Kim N. Dietrich, and Bruce P. Lanphear. “Impact of Early-Life Bisphenol A Exposure on Behavior and Executive Function in Children.” Pediatrics 128, no. 5 (November 2011): 873–82. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1335. - “NTP-CERHR Monograph on the Potential Human Reproductive and Developmental Effects of Di-Isodecyl Phthalate (DIDP).” National Toxicology Program, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Center for the Evaluation of Risks to Human Reproduction, NIH Publication No. 03-4485. April 2003.

- Lindström, Karolina, Birger Winbladh, Bengt Haglund, and Anders Hjern. “Preterm Infants as Young Adults: A Swedish National Cohort Study.” Pediatrics 120, no. 1 (July 2007): 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-3260.

Dr. Ami Zota, Associate Professor at the Department of Environmental & Occupational Health at the George Washington University (GWU) Milken Institute School of Public Health, created a platform to amplify underrepresented voices in science and environmental health. She launched her vision, Agents of Change, in 2019 with its first cohort of changemakers.

The high-achieving crew included Dr. MyDzung Chu, a first-generation Vietnamese-American, environmental epidemiologist, new mother, and postdoctoral scientist at the GWU Milken Institute School of Public Health. MyDzung is invested in understanding social determinants of health and environmental exposures within the home, workplace, and neighborhood contexts. Her current research investigates the impact of federal housing assistance on residential environmental exposures for low-income communities.

In her Agents of Change blog, Why Housing Security is Key to Environmental Justice, MyDzung examines the intersection of housing, racism, and environmental justice, and its effects on population health. She challenges us: “It is time for the environmental health community to step up and be at the forefront of addressing housing insecurity.”

MyDzung is practicing what she preaches – and blazing a trail while doing it. In her local community, MyDzung organizes with residents and non-profit organizations for affordable housing, equitable development, and anti-displacement policies. Her dissertation research examined socio-contextual drivers of disparities in indoor and ambient air pollution and poor housing quality for low-income, immigrant, and Black and Brown households. In a study published in Environmental Research, MyDzung and colleagues found that renters in multifamily housing were exposed to higher levels of fine particulate matter indoors that homeowner households, due to a combination of building factors and source activities that may be modifiable, such as building density, air exchange, cooking, and smoking.

MyDzung has a PhD in Population Health Sciences from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, a MSPH in Environmental-Occupational Health and Epidemiology from Emory University, and a BA in Neuroscience from Smith College.

To keep up to date with MyDzung’s research and impacts, you can follow her on Twitter or LinkedIn. And, click this link to learn more about her colleagues at Agents of Change. Thanks, MyDzung, for your leadership and courage to advance real change.

Plastic is a ubiquitous part of our everyday lives, and its global production is expected to more than triple between now and 2050. According to industry projections, we will create more plastics in the next 25 years than have been produced in the history of the world so far.

The building and construction industry is the second largest use sector for plastics after packaging.1 From water infrastructure to roofing membranes, carpet tiles to resilient flooring, and insulation to interior paints, plastics are ubiquitous in the built environment.

These plastic materials are made from oil and gas. And, due to energy efficiency improvements, for example–in building operations and transportation–the production and use of plastics is predicted to soon be the largest driver of world oil demand.2

Plastic building products are often marketed in ways that give the illusion of progress toward an ill-defined future state of plastics sustainability. For the past 20 years, much of that marketing has focused on recycling. But for a variety of reasons, these programs have failed.

A recent study from the University of Michigan makes it clear that the scale of post-consumer plastics recycling in the US is dismal.3 Only about 8% of plastic is recycled, and virtually all of that is beverage containers. Further, most of the recyclate is downcycled into products of lower quality and value that themselves are not recyclable. For plastic building materials, the numbers are more dismal still. For example, carpet, which claims to have one of the more advanced recycling programs, is recycled at only a 5% rate, and only 0.45% of discarded carpet is recycled into new carpet. The rest is downcycled into other materials, which means their next go-around these materials are destined to be landfilled or burned.4 After 20 years of recycling hype, post-consumer recycling of plastic building materials into products of greater or equal value is essentially non-existent, and therefore incompatible with a circular economy.

Why isn’t plastic from building materials recycled?

Additives (which may be toxic), fillers, adhesives used in installation, and products made with multiple layers of different types of materials all make recycling of plastic building materials technically difficult. Lack of infrastructure to collect, sort, and recycle these materials contributes to the challenge of recycling building materials into high-value, safe new materials.

Manufacturers have continued to invest in products that are technically challenging to reuse or recycle – initially cheaper due to existing infrastructure – instead of innovating in new, circular-focused solutions. Additionally, their investment in plastics recycling has been paltry. In 2019 BASF, Dow, ExxonMobill, Shell and numerous other manufacturers formed the Alliance to End Plastic Waste (AEPW) and pledged to invest $1.5 billion over the next five years into research and development of plastic waste management technologies. Compare that to the over $180 billion invested by these same firms in new plastic manufacturing facilities since 2010.5

Globally, regulations that discourage or ban landfilling of plastics have, unfortunately, not led to more recycling overall. Instead, burning takes the place of landfilling as the eventual end of life for most plastics.

Confusing rhetoric around plastic end of life options can make this story seem more complicated than it is.6

- “incineration” or “waste to energy” burns plastic for energy.

- “Plastic-to-fuel” or “gasification” or “pyrolysis” generates fuel. This output is rarely used for anything but burning due to the additional processing required to use for any other purpose.

- “Chemical recycling” could, in theory, lead to new plastic products. This technology is unproven and currently not a scalable solution. The outputs are often burned due to low quality.

Plastic waste burning, regardless of the euphemism employed, is a well established environmental health and justice concern.

Burning plastics creates global pollution and has environmental justice impacts.

In its exhaustive 2019 report, the independent, nonprofit Center for International Environmental Law (CEIL) documents how burning plastic wastes increases unhealthy toxic exposures at every stage of the process. Increased truck traffic elevates air pollution, as do the emissions from the burner itself. Burned plastic produces toxic ash and residue at approximately one fifth the volume of the original waste, creating new disposal challenges and new vectors of exposure to additional communities that receive these wastes.7

In the US, eight out of every 10 solid waste incinerators are located in low-income neighborhoods and/or communities of color.8 This means, in some cases, the same communities that are disproportionately burdened with the pollution and toxic chemical releases related to the manufacture of virgin plastics are again burdened with its carbon and chemical releases when it is inevitably burned at the end of its life.

The issue is global in scale. A recent report by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) found that “plastic waste incineration has resulted in disproportionately dangerous impacts in Global South countries and communities.” The Global Alliance for Incineration Alternatives (GAIA), a worldwide alliance of more than 800 groups in over 90 countries, has been working for more than 20 years to defeat efforts to massively expand incineration, especially in the Global South. GAIA members have identified incineration not only as an immediate and significant health threat in their communities, but also a major obstacle to resource conservation, sustainable economic development, and environmental justice.

Where do we go from here?

- Minimize production of virgin plastic. This should be the main focus of any plastic waste reduction plan and part of any comprehensive climate change initiative. Policies banning single use plastics or banning the construction of new plastic production facilities or facility expansions are two example solutions cited by GAIA.9 Less plastic means less waste and less material to incinerate.

- Invest in true circular economy initiatives. These may include, for example: extended producer responsibility programs, materials passports, materials disclosure, elimination of toxic chemical additives, product as a service models, and recycling facilities that support upcycling. By shifting industry investments toward circular economy infrastructure – instead of the nearly $200 billion investments in increased manufacturing and burning capacity – the plastic industry could start to be part of the solution of reducing plastic waste.

- When evaluating the “expense” of recycling and circularity vs business-as-usual, a fair calculation for the latter needs to include all costs associated with the production, use, and end of life impacts of plastics. That “cheap” vinyl floor is no longer so inexpensive when the full costs of global pollution and the health burdens of people of color and low income communities are included in the math. Externalities must be a part of the equation.

What is unquestionable is this: Today our only choices for plastic waste are to burn or landfill most of it. Expanding plastics production and incineration is a conscious decision to perpetuate well documented, fully understood inequity and injustice in our building products supply chain.

The folks at The Story of Stuff cover this in The Story of Plastics, four minute animated short suitable for the whole family. Comedian John Oliver tells the “R-rated” version of the story with impeccable research and insightful humor in his HBO show Last Week Tonight. It’s worth a look to learn exactly how the plastics industry uses the illusion of recycling to sell ever increasing volumes of plastic. Without manufacturer responsibility and investment, efforts to truly incorporate plastic into a circular economy have little chance of success.

SOURCES

- https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution

- https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/bee4ef3a-8876-4566-98cf-7a130c013805/The_Future_of_Petrochemicals.pdf See page 18, 30.

https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/us-energy-facts/ - https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab9e1e/pdf

- https://carpetrecovery.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CARE-2019-Annual-Report-6-7-20-FINAL-002.pdf

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jan/21/founders-of-plastic-waste-alliance-investing-billions-in-new-plants

- https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/False-solutions_Nov-9-2020.pdf

- https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Plastic-and-Climate-FINAL-2019.pdf

- https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d14dab43967cc000179f3d2/t/5d5c4bea0d59ad00012d220e/1566329840732/CR_GaiaReportFinal_05.21.pdf

- https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/False-solutions_Nov-9-2020.pdf

Coming Clean and EJHA teamed up with NRDC, Rashida Jones, and Molly Crabapple to tell the stories of vulnerable fenceline communities living near over 12,000 high-risk chemical facilities in America, urging action to protect their health and safety.

Watch ChemSec’s skit about the SIN List, to learn why hazardous chemicals should be removed from products due to the health and environmental risks they present.

In Louisiana, the factories that make the chemicals and plastics for our building products are built literally upon the bones of African Americans. Plantation fields have been transformed into industrial fortresses.

A Shell Refinery1 sprawls across the former Bruslie and Monroe plantations. Belle Pointe is now the DuPont Pontchartrain Works, among the most toxic air polluters in the state.2 Soon, the Taiwan-based Formosa Plastics Group intends to build a 2400-acre complex of 14 facilities that will transform fracked gas into plastics. It will occupy land that was formerly the Acadia and Buena Vista plantations, and not incidentally, the ancestral burial grounds of local African American residents, some of whom trace their lineage back to people enslaved there.3

Formosa has earned a reputation of being a poor steward of sacred places. Local residents have petitioned the Governor to deny permits for the facility, citing a long list of environmental health violations in its existing Louisiana facilities, including violations of the Clean Air Act every quarter since 2009.4 The scofflaw company was found to have dumped plastic pellets known as “nurdles” into the fragile ecosystem of Lavaca Bay on the Gulf of Mexico for years – leading to a record $50 million settlement with activists in that community in 2019.5

In the Antebellum South, formerly enslaved people often homesteaded on lands that were part of or near the plantations they once worked. They established communities of priceless historical and cultural worth, towns such as Morrisonville, Diamond, Convent, Donaldsonville, and St. James. Donaldsonville, Louisiana, is the town that elected Pierre Caliste Landry, America’s first African American mayor in 1868, just three years after the end of the Civil War. This part of Louisiana holds many layers of complex and deep African American history.

But in the last 75 years, since World War II, these communities have been overrun by petrochemical industry expansion enabled by governments wielding the clout of Jim Crow laws to snuff out any opposition or objection. Towns like Morrisonville and Diamond have been bought up to accommodate plant expansion. Residents have been forced to move out, their history and heritage literally paved over. It wasn’t until 1994 that the River Road African American Museum was established to preserve and present the history of the Black population as distinct from plantation representations of slavery. According to Michael Taylor, Curator of Books, Louisiana State University Libraries: “Only in the last few decades have historians themselves begun to appreciate the complexity of free black communities and their significance to our understanding not just of the past, but also the present.”6

Charting a New Way Forward—Together

Virtually every building product we use today contains a petrochemical component that originates from heavily polluted communities, frequently home to people of color. As the green building movement searches for ways to enhance diversity, inclusion and equity, how might it address the legacies of injustice that are tied to the products and materials we use every day?

Architect, Zena Howard, FAIA, offered insight in her 2019 J. Max Bond Lecture, Planning to Stay, keynoting the National Organization of Minority Architects national conference. Howard, known for her work on the design team for the breathtaking Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, most often works with people in communities whose culture and heritage were “erased” by urban renewal in the 1960’s. In Greenville, North Carolina, she looked to people from the historically African American Downtown Greenville community and Sycamore Hill Missionary Baptist Church Congregation to guide the planning and design process for a new town common and gateway plaza. The goal was not to “replicate” the lost community, but to bring its history and present day aspirations to life in the new design. In Vancouver, British Columbia, the development plan for a neighborhood founded by African Canadian railroad porters included an unprecedented chapter on “reconciliation and cultural redress.” The key to such efforts, according to Howard is co-creation and meaningful collaboration, whose Greek roots, she notes, mean “to labor together.”

How might we labor together to address environmental injustice when evaluating the overall healthfulness and equity of our building materials? The precedent of “insetting” suggests an approach.

Insetting has been pioneered by companies whose supply chains rely upon agricultural communities across the globe. According to Ceres, insetting is “a type of carbon emissions offset, but it’s about much more than sequestering carbon: It’s also about companies building resiliency in their supply chains and restoring the ecosystems on which their growers depend.”

In previous columns, I’ve addressed concerns about the social in industrial communities, e.g., proposals that perpetuate disproportionate pollution impacts when buying offsets rather than addressing emissions from a specific facility. Applying the “insetting” approach we might ask our materials manufacturers—and the communities that are home to the building materials industries—what steps can we take to encourage manufacturers to “labor with” communities seeking environmental justice, such as those along the Mississippi River? Can we, together, resurrect and restore their history, reconcile and redress historical wrongs, and build a healthier future for all?

Black History

Month Readings

To learn more about the history and present day conditions of Cancer Alley, see these excellent articles from The Guardian and Pro Publica: https://www.ehn.org/search/?q=cancer+alley

You can watch to Zena Howard’s J. Max Bond lecture, Planning to Stay, here: https://vimeo.com/378622662

You can learn more about the River Road African American History Museum here: https://africanamericanmuseum.org/

SOURCES

- Terry L. Jones, “Graves of 1,000 Enslaved People Found near Ascension Refinery; Shell, Preservationists to Honor Them | Ascension | Theadvocate.Com,” accessed February 18, 2020, https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/communities/ascension/article_18c62526-2611-11e8-9aec-d71a6bbc9b0c.html.

- Oliver Laughland and Jamiles Lartey, “First Slavery, Then a Chemical Plant and Cancer Deaths: One Town’s Brutal History,” The Guardian, May 6, 2019, sec. US news, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/may/06/cancertown-louisiana-reserve-history-slavery.

- Sharon Lerner, “New Chemical Complex Would Displace Suspected Slave Burial Ground in Louisiana’s ‘Cancer Alley,’” The Intercept (blog), December 18, 2019, https://theintercept.com/2019/12/18/formosa-plastics-louisiana-slave-burial-ground/.

- Louisiana Bucket Brigade, “Sign the Petition,” Change.org, accessed February 25, 2020, https://www.change.org/p/governor-edwards-stop-the-formosa-chemical-plant.

- Stacy Fernández, “Plastic Company Set to Pay $50 Million Settlement in Water Pollution Suit Brought on by Texas Residents,” The Texas Tribune, October 15, 2019, https://www.texastribune.org/2019/10/15/formosa-plastics-pay-50-million-texas-clean-water-act-lawsuit/.

- LSU Libraries, “Free People of Color in Louisiana,” LSU Libraries, accessed February 18, 2020, https://lib.lsu.edu/sites/all/files/sc/fpoc/history.html.

Pharos makes it easier than ever to prioritize chemicals management and identify safer alternatives to chemicals of concern. We’re excited to share several resources to help shape the next generation of green chemistry leaders:

- Two case studies detailing how Klean Kanteen and University of Victoria use Pharos to improve their work

- A webinar featuring safer chemistry research from the students of Dr. Meg Schwarzman, an environmental health scientist at University of California, Berkeley. Jeremy Faludi, Ph.D., Delft University of Technology also presents his research in 3D printing. Both share success stories using Pharos to support research and chemical alternatives assessment courses.

- Example assignments and curriculum from Assistant Professor Heather Buckley, Ph.D. of the University of Victoria.

Power Your Work

with Pharos

Educators are doing important work and making our homes, workplaces and communities safer to inhabit. Pharos can help you meet your goals and streamline your work. In addition to our standard online access, now there are more ways to access chemical hazard data!

- Connect to the Pharos API to reduce manual entry and ensure you have the most current information available.

- Not able to take our API yet, but still manually managing lists of lists for your EHS, regulatory, or sustainability programs? We offer low-cost standard and custom data downloads from Pharos to power your internal chemicals management programs.

If you are interested in further details, or subscribing to Pharos, more information is available here.

ChemSec’s Marketplace connects products like this car seat with safer alternatives to hazardous chemicals, offering a platform for them to find better matches and reduce their environmental impact.

Phase 2 of this report is the first of its kind plant-by-plant accounting of the production, use, and releases of chlorine and related pollution around the world. It is intended to inform the efforts of building product manufacturers to reduce pollution in their supply chains.

Chlorine is a key feedstock for a wide range of chemicals and consumer products, and the major ingredient of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic. The report includes details aboutthe production technologies used and markets served by 146 chlor-alkali plants (60 in Asia) and which of these plants supply chlorine to 113 PVC plants (52 in Asia). The report answers fundamental questions like:

- Who is producing chlorine?

- Who is producing PVC?

- Where? How much? And with what technologies?

- What products use the chlorine made in each plant?

Key findings include:

- Over half of the world’s chlorine is consumed in the production of PVC. In China, we estimate that 74 percent of chlorine is used to make PVC.

- 94 percent of plants in Asia covered in this report use PFAS-coated membrane technology to generate chlorine.

- In Asia the PVC industry has traded one form of mercury use for another. While use of mercury cell in chlorine production is declining, the use of mercury catalysts in PVC production via the acetylene route is on the rise. 63 percent of PVC plants in Asia use the acetylene route.

- 100 percent of the PVC supply chain depends upon at least one form of toxic technology. These include mercury cells, diaphragms coated with asbestos, or membranes coated with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), used in chlorine production. In PVC production, especially in China, toxic technologies include the use of mercury catalysts.

Supplemental Documents:

Equity

Equity Health

Health Pollution

Pollution