READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORTCurrent climate action plans are bold, they are necessary, they feel impossible, and they are coming into the consciousness of all concerned (and unconcerned), decades after the early reports should have been taken seriously.

At this point, there is an urgency because people are now experiencing the effects of a warming planet:storms, fires, rising tides, health impacts from warmer temperatures, and more.

To date, climate plans have focused on strategies related to renewable and clean energy, greater efficiency, emissions reduction, etc., especially as it relates to building operations and transportation. However, that is only one side of the (enormous) coin, and it misses key opportunities on the opposite side. It is akin to making the decision to improve your health by incorporating an exercise plan, but continuing a diet of nutritionally deficient and unhealthy foods. You will only get so far, and your dedication to exercise will be undercut by your fast food burgers and supersized fries.

The other side of the coin? If building and transportation energy and emissions reduction is “heads,” what could be so immense that it fills the flipside? The “tails” of that coin is the vast quantities of products being produced, its emissions and pollution, and the need for toxic chemical mitigation. The missing piece in effective climate mitigation and improved global health is a toxic-free, recyclable product cycle (low-waste and closed-loop).

The Link Between Emissions, Circular Economy, and Chemicals

Climate plans must include Circular Economy strategies, and a circular economy is possible only if safe chemistries are used as inputs to products.1 The Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s (EMF) September 2019 report: Completing the Picture: How the Circular Economy Tackles Climate Change makes the case that we must address the product cycle as a core part of climate action plans.2 According to the report, “to date, efforts to tackle the [climate] crisis have focused on a transition to renewable energy, complemented by energy efficiency. Though crucial and wholly consistent with a circular economy, these measures can only address 55% of emissions. The remaining 45% comes from producing the cars, clothes, food, and other products we use every day.”

There is more than just emissions that makes the product cycle a critical component of an effective climate strategy. At Habitable, our research shows that there is a related and similar urgency in addressing severe health crises, impacting marginalized communities the hardest, but also now affecting a larger population of people. Our plans—starting with transparency (requesting manufacturers provide the public with a complete list of product ingredients); full testing of all chemicals for human and environmental health impacts; and innovation to new, “green” (safer) chemicals—are bold, necessary and they also feel impossible.

The EMF Completing the Picture report makes the case that we must fundamentally change how our products are made. A key recommendation in reducing emissions is to “design out waste and pollution.” To be even more precise, designing the toxics out of our products is key to eliminating waste and creating the safe and circular economy that is the cornerstone of any climate solution, an inextricable element in human and environmental health.

A companion report by Google, in partnership with EMF, The Role of Safe Chemistry and Healthy Materials in Unlocking the Circular Economy, emphasizes that toxic chemical mitigation is a precursor to a circular economy. It suggests that “the short- and long-term impacts of these new chemical substances has lagged behind the drive to create new molecules and materials. We can see the consequences around us, including ‘sick building syndrome,’ flame retardants accumulating in human breast milk and being passed along to newborns, or entire city populations toxified from local environmental exposures and contaminated drinking water.” The authors of the report put out a challenge to the world’s chemists and material scientists to not only develop molecules and materials that achieve a performance or aesthetic outcome, but also to ensure that these substances are safe for people and the environment, can be cycled and used to create future products, and retain economic value throughout its lifecycle. Safer chemistry is the key to unlock a circular economy.

The health impacts related to our petrochemical and hazardous chemical-dependent product economy are real, but are often unseen or unrecognized. Globally declining sperm counts and reproductive disorders are linked to chemicals in our plastics,3 and a growing library of peer-reviewed studies link today’s epidemic health issues—cancer, diabetes, obesity, asthma and autism—to endocrine-disrupting and neurotoxic chemicals.4 These data often take a back seat to the climate crisis in our headlines, but they too are growing worse and in need of bold action.

“Better Living Through Chemistry” vs Better Chemistry for Healthier Living

DuPont (and other chemical companies) did not get it right with the blanket phrase, “Better Living Through Chemistry.”

Has there been some great progress and benefits from innovative products that use new chemistries and materials?—yes, of course. That said, a significant lack of understanding of the toxicological effects on humans and the environment have come at great cost. We are finding that the tradeoffs are severe—though today, like the early science on climate change, most people are unaware of this silent epidemic, and tend to accept the rise in cancer, autism, fertility problems, and developmental issues in children, as only an unfortunate part of life—they or their loved ones just pulled a short straw, bad luck.

In 1970, the U.S. produced 50 million tons of synthetic chemicals.5 In 1995, the number tripled to 150 million tons, and today, that number continues to increase.6 Very few of the tens of thousands of chemicals in the marketplace are fully tested for health hazards, and details on human exposure to these chemicals is limited.7 We are exposed to these chemicals every day, in varying quantities and combinations. Over a lifetime, the small exposures add up. Science-based predictions of health outcomes from long-term exposure continue to emerge,8 but add on the component of a warming climate and a new layer of concern is revealing itself.9

Both/And Solution

The best climate plans are holistic. They recognize and include strategies from both the clean and renewable energy effort and safe and circular product cycle. The threats and impacts of climate change and toxic chemicals are synergistic, as are the solutions. They must be tethered in order to be effective. In fact, ignoring the chemical/material side of the coin will undermine progress on climate and energy solutions.

We know better, and we can do better.

As energy efficiency and renewable energy gains reduce the carbon footprint of the transportation and building operations sectors, addressing product production assumes an even greater importance. Successfully addressing climate change requires a revolutionary change in how we design and manufacture materials, towards a circular, closed-loop economy. But materials cannot flow effectively in a closed-loop if they are contaminated with toxic chemicals. Safe first, and then circular is possible.

The urgency to mitigate toxics must be on par with the urgency for clean and renewable energy – they are two sides of the same coin. Failing to recognize this, and create holistic, compatible solutions, will undermine our goals to manage climate change and improve global health.

SOURCES

- “What Is a Circular Economy? | Ellen MacArthur Foundation,” accessed November 25, 2019, https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/concept.

- “Circular Economy Reports & Publications From The Ellen MacArthur Foundation,” accessed November 25, 2019, https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications.

- Teresa Carr, “Sperm Counts Are on the Decline – Could Plastics Be to Blame?,” The Guardian, May 24, 2019, sec. US news, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/may/24/toxic-america-sperm-counts-plastics-research.

- Naoko OHTANI et al., “Adverse Effects of Maternal Exposure to Bisphenol F on the Anxiety- and Depression-like Behavior of Offspring,” The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 79, no. 2 (February 2017): 432–39, https://doi.org/10.1292/jvms.16-0502.

- Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Practice, and Medicine.

- Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Practice, and Medicine.

When celebrated Victorian painter Edward Burne-Jones learned that a favorite pigment—it was called Mummy Brown—was in fact manufactured from the desecrated Egyptian dead, he banished it from his palette and bore his remaining tubes to a solemn burial in his English garden.[1] Once you know better, you have to do better.

Transparency in the supply chain can reveal inconvenient truths about favored products. A fascinating new article about the plywood supply chain brings into view new incentives to stop using fly ash in building products.

In What You Don’t See, Brent Sturlaugson, a practicing architect and associate professor at the University of Kentucky attempts a full accounting of the environmental, social, financial, and political impacts he attributes to the supply chain for Georgia Pacific (GP) plywood. He opens his ledger at the world’s largest open pit coal mine, Peabody Energy’s North Antelope Rochelle Mine, located in the heart of Wyoming’s Thunder Basin National Grasslands. From there the environmental and health costs add up, many of them allocated to the utility that powers GP’s Madison, Georgia plant. The Robert W. Scherer Plant in Monroe County, Georgia, has been calculated to be the largest, dirtiest coal fired power plant in the United States.[2]

This caught the attention of the Healthy Building Network (HBN) Research Team, who previously identified this power plant as a huge mercury polluter. It is also the leading supplier of fly ash to U.S. carpet companies that use the ash as filler—replacing limestone in carpet tiles—in order to qualify for recycled content credits in LEED, the Living Building Challenge, and various government procurement standards. What we had not realized was that the Scherer plant relied upon a single source of coal, the North Antelope Rochelle Mine. HBN and others[3] have long recommended against the use of fly ash in various building products because of the heavy metal content of the ash and the cost incentives fly ash “recycling” provide to continue burning coal – absent reuse, the fly ash must be expensively managed as a hazardous waste. What You Don’t See compels us to consider the ash as processed coal, the original raw material ingredient. In this case, coal mined from the seam of a single, particularly gnarly open pit mine.

Located near Gillette, WY, the mine occupies territory whose history is steeped in the genocide of Indigenous Peoples who negotiated treaty rights to the region in the mid-1800’s. By the end of the century they lost their livelihood to the extermination of the American Bison, and then their land to well-documented, systemic treaty violations. Environmentalists and ranchers alike view the mine as a disaster for the local and global environment. It is a financial disaster for the American taxpayer, according to the U.S. General Accounting Office which cites the mine as an example of corrupt Bureau of Land Management practices that include no bid contracts, financial terms that deprive the U.S. of fair market value, and a brazen lack of transparency. All in violation of federal laws and regulations.

Squandered water and subsidized carbon emissions are only the beginning of the staggering sustainability losses from this coal, according to Sturlaugson’s detailed accounting, which also includes: “dark money” political contributions from the Koch brothers, the use of bankruptcy laws to renege on union pension obligations, and significant releases of toxic chemicals that can cause cancer, respiratory disease, and reproductive and neurological impacts.

Like the rich umber of Mummy Brown pigment, recycled coal ash in building products has a superficial appeal, until you learn the truth. What You Don’t See opens our eyes even wider to the reasons why the use of coal ash—processed coal—is unacceptable in green buildings and building products. Burying these products in our gardens or landfills won’t do. But we can and must root them out of our green rating system and recycling incentives.

SOURCES

- From the article Blue As Can Be, by Simon Schama, a fascinating history of prized (frequently toxic) artistic pigments. Schama, Simon. “Blue as Can Be.” The New Yorker, September 3, 2018.

- Schneider, Jordan, Travis Madsen, and Julian Boggs. “America’s Dirtiest Power Plants: Their Oversized Contribution to Global Warming and What We Can Do About It.” Environment America Research & Policy Center, September 2013. https://environmentamericacenter.org/sites/environment/files/reports/Dirty%20Power%20Plants.pdf.

- BuildingGreen and Perkins+Will are among those that have recommended against the use of coal fly ash in certain building products. Wilson, Alex. “OP-ED: EBN’s Position on Fly Ash.” Environmental Building News, August 30, 2010. https://www.buildinggreen.com/op-ed/ebns-position-fly-ash.; Glazer, Breeze, Craig Graber, Carolyn Roose, Peter Syrett, and Chris Youssef. “Fly Ash in Concrete.” Perkins+Will, November 2011. http://assets.ctfassets.net/t0qcl9kymnlu/1Tx57nRsWYYMEC824CkOaI/38239c5e0fb2044af10bc2b1fac38cf8/FlyAsh_WhitePaper.pdf.

- Vallette, Jim, Rebecca Stamm, and Tom Lent. “Eliminating Toxics in Carpet: Lessons for the Future of Recycling.” Healthy Building Network, October 2017. https://habitablefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/81-eliminating-toxics-in-carpet-lessons-for-the-future-of-recycling.pdf. (see p. 21)

- Walsh, Bill. “Home Depot Raises The Bar On Hazard Avoidance – New Chemical Strategy Is An Important Step Towards Healthier Product Options.” Healthy Building Network Blog, October 25, 2017. https://habitablefuture.org/resources/home-depot-raises-the-bar-on-hazard-avoidance/.

Discover how bisphenols and phthalates, commonly used in plastics for added strength or flexibility, can disrupt hormone function, and learn ways to reduce their use for improved health in this informative video.

Phase 1 of this report is the first of its kind plant-by-plant accounting of the production, use, and releases of chlorine and related pollution around the world. It is intended to inform the efforts of building product manufacturers to reduce pollution in their supply chains.

Chlorine is a key feedstock for a wide range of chemicals and consumer products, and the major ingredient of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic. The report includes details about the largest 86 chlor-alkali facilities and reveals their connections to 56 PVC resin plants in the Americas, Africa and Europe. (The second phase of this project will inventory the industry in Asia.) A substantial number of these facilities, which are identified in the report, continue to use outmoded and highly polluting mercury or asbestos.

Demand from manufacturers of building and construction products now drives the production of chlorine, the key ingredient of PVC used in pipes, siding, roofing membranes, wall covering, flooring, and carpeting. It is also an essential feedstock for epoxies used in adhesives and flooring topcoats, and for polyurethane used in insulation and flooring.

Key findings include:

- In the United States, the chlor-alkali industry is the only industry that still uses asbestos, importing 480 tons per year on average for 11 chlor-alkali plants in the country (including 7 of the 12 largest plants).

- The only suppliers of asbestos to the chlor-alkali industry are Brazil (which banned its production, although exports continue for the moment) and Russia, whose Uralasbest mine is poised to become the sole source of asbestos once Brazil’s ban is in place.

- The US Gulf Coast is the world’s lowest-cost region for production of chlorine and its derivatives. It is home to 9 facilities that use asbestos technology, and some of the industry’s worst polluters including 5 of the 6 largest emitters of dioxin.

- One Gulf Coast facility has been found responsible for chronic releases of PVC plastic pellets into the Gulf of Mexico watershed.

- The US, Russia and Germany are the only countries in this report that allow the indefinite use of both mercury and asbestos in chlorine production.

- The world’s two largest chemical corporations – BASF and DowDuPont – have not announced any plans to phase out the use of mercury and asbestos, respectively, at their plants in Germany.

- Chlor-alkali facilities are major sources of rising levels of carbon tetrachloride, a potent global warming and ozone depleting gas, in the earth’s atmosphere.

- Far more chlorinated pollution, such as dioxins and vinyl chloride monomer, is released from chlor-alkali plants that produce feedstocks for the PVC industry than from plants that produce chlorine for other uses.

Supplemental Documents:

The Future of Petrochemicals report explores the role of the petrochemical sector in the global energy system and its increasing significance for energy security and the environment, highlighting the need for attention from policymakers.

More than 15% of North Americans report an unusual hypersensitivity to common chemical products such as those used in new-home construction. Another 40% may have mild symptoms of which they’re unaware.

This book explores the journey of designing and building a prototype healthy house, aiming to provide a sanctuary for healing and addressing environmental hypersensitivity, serving as a comprehensive guide for those interested in healthier approaches to design, construction, or remodeling.

Circular design encourages us to rethink business models and how we make products, and to consider the systems surrounding them. But we also need to think about the materials we use – and the chemistry behind them.

To create a truly sustainable circular economy, we must know what’s in the materials and products we choose, and those choices should focus on optimized chemistry for human and environmental health. Only then will we have the building blocks for a circular economy.

Chemistry is an important part of the value stream.

A circular economy is fueled by the creation and retention of value. By keeping material streams as pure as possible from the beginning and through the entire use cycle, the full value of a material is retained. Value retention is key to activating the systems that make the circular economy function, including the incentive for manufacturers to take back products because they have value and the motivation for entrepreneurs to create robust secondary markets.

Not all materials are fit for a circular economy, however. When they contain chemicals that are hazardous for humans or the environment, they provide little to no value in supporting circularity. Fortunately there are ways to choose materials that are safe AND circular so you can build a better offering for your users and introduce valuable inputs for a sustainable economy.

New Safe and Circular learning modules provide an excellent place to start.

To help designers, entrepreneurs, and innovators make positive materials choices and integrate better chemistry into the design process from the very start, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and the Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Institute (C2C PII) have released a new series of advanced learning modules as part of the foundation’s Circular Design Guide, which was co-created with IDEO.

You’ll find them in the Methods section of the guide (scroll to the “Advanced” section), which aims to fuel design thinking for the circular economy by challenging traditional design methods, delivering new approaches, and introducing users to circular economy concepts as well as techniques updated for this new economic framework.

The new modules include:

- Materials Journey Mapping: Explore how materials choices can influence a design to fit a circular economy.

- Product Redesign Workshop: Explore the implications of safe and circular material strategies on the design process through a redesign workshop.

- Material Selection: Choose the right materials for your new circular design.

- Moving Forward with Materials: Explore the next steps for making safe and circular material choices a driver for innovation in your design process.

Check out Safe & Circular by Design: Making Positive Material Choices, a podcast hosted by Emma Fromberg from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and featuring Stacy Glass, director of ChemFORWARD, alongside other leaders in the safe and circular movement.

While attending a 2018 meeting of U.S. EPA’s National Environmental Justice Advisory Council (NEJAC) in Boston, I heard the testimony of Delma and Christine Bennet. They live in Mossville, LA, amidst what is likely the nation’s largest concentration of PVC (polyvinyl chloride) manufacturing facilities. I was there to present the findings of HBN’s inventory of pollution associated with the chlorine/PVC supply chain.

Our study found, among other things, that the Gulf Coast region (which includes Mossville) is home to nine facilities that use outmoded asbestos technology, and home also to some of the industry’s worst polluters: Five of the six largest emitters of dioxins––a long lasting, extremely toxic family of hazardous waste that causes cancer and many other health impacts, are located there. The Bennets reminded the EPA that according to studies by a division of the Centers for Disease Control, Mossville residents have three times higher levels of dioxin in their blood than average Americans, and the dioxin levels found in their yards and attic dust exceed regulatory standards typically used for toxic waste remediations of industrial sites. Even the vegetables in their gardens tested positive for dioxin.

When I think about why we fight so hard to exclude PVC from any palette of green, healthy, or sustainable building materials, I think first of people like Delma and Christine. I then think about the many non-profits, government agencies, and private enterprises dedicated to recycling. Way back in the 1990’s, the industry Association of Plastic Recyclers declared PVC a contaminant to the recycling stream. A generation later, a 2016 study by the Circular Economy evangelist Ellen MacArthur Foundation called out PVC packaging for global phase-out, citing low recycling rates and chemical hazard concerns. Much of the concern about PVC packaging is driven by worries about ocean pollution. HBN’s study found that at least one U.S. PVC manufacturer is routinely dumping tons of PVC pellets into local waterways and refusing to stop even after being ordered to do so by the state of Texas.

The list goes on. Our report documents the types of industrial pollution in addition to dioxin that could be reduced or avoided by a switch to more recyclable plastics that are not made with the chlorine that is an essential ingredient of PVC, including ozone depleting and potent global warming gasses. HBN’s earlier studies have documented the hazards posed by legacy pollutants that are returning to our consumer products in recycled PVC content––heavy metals such as lead, and endocrine-disrupting plasticizers known as phthalates.

There is a better way.

There is virtually no use of PVC in building products that could not be replaced with another plastic or other material. Indeed, from siding, to wallpaper, to window frames, PVC has displaced materials that are more recyclable, such as aluminum and paper. Because the industry is not held accountable for the environmental health damages wrought in places like Mossville, PVC has artificially low costs that present barriers to entry, or inhibit market expansion of less hazardous, more sustainable alternatives.

That is why PVC should not be part of any building, or any building rating system, that claims to advance environmental and health objectives. It’s not green. It’s not healthy. It’s not sustainable. It’s just cheap––for us. Because folks like Delma and Christine Bennet pay the true cost.

Know Better

Learn more about the implications of chlorine as a feedstock in plastics in HBN’s Chlorine and Building Materials report.

As noted in Healthy Building Network’s(HBN) Chlorine and Building Materials report, chlorine production is a major source of releases of carbon tetrachloride, a potent global warming and ozone depleting gas as well as a carcinogen.

As the report reminds us, it’s important to consider not only the use-phase impacts of building products, but the entire life cycle, including primary chemical production that’s several steps back from final product manufacture.

Blowing agents are used in plastic foam insulation to create the foam structure and also contribute to the insulative properties. Over the years, manufacturers have cycled through a range of fluorocarbons as each prior class is phased out due to environmental concerns – from ozone depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) to less ozone depleting hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) to the non-ozone depleting but high global warming potential hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) currently common in many types of foam insulation. Manufacturers have now begun the latest shift to next generation, low global warming potential hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs). For extruded polystyrene (XPS), this translates to a shift from commonly used HFC-134a with a global warming potential (GWP) of 1,430 to HFO-1234ze with a GWP of six.2

The summary of these chemical transitions only tells part of the story. While HFOs do not directly deplete the ozone layer or significantly contribute to global warming, many HFOs use carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) as a chemical feedstock. This includes HFO-1234ze, the replacement for HFC-134a (which does not use CCl4) in many applications.3

How is it that this ozone depleting substance is still in use? Many uses of carbon tetrachloride were phased out in 1995, under the terms of the Montreal Protocol to protect the ozone layer. But the Montreal Protocol phase-outs exempted the use of CCl4 as a chemical feedstock, under the assumption that emissions would be minor.4 However, carbon tetrachloride “is not decreasing in the atmosphere as rapidly as expected” based on its known lifetime and emissions, according to a 2016 report on the Mystery of Carbon Tetrachloride. The authors of this report concluded that emissions of carbon tetrachloride during its production, and fugitive emissions from its use as a chemical feedstock, have been significantly unreported and underestimated.5

Production of carbon tetrachloride is likely to increase as industry replaces HFC blowing agents (and refrigerants), most of which aren’t produced with carbon tetrachloride, with HFOs that do use CCl4 as a feedstock.[6] With increased production and use of carbon tetrachloride, increased emissions are expected – and that’s bad news for the earth’s recovering ozone layer.

We recommend against the use of plastic foam insulation whenever possible, but if you do use it, some products are available that use other, less impactful, blowing agents, including hydrocarbons and water. For more recommendations about preferable insulation from a health hazard perspective, review our product guidance at informed.habitablefuture.org.

SOURCES

- According to US Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) data from 2012 to 2015, half of the 10 leading sources of carbon tetrachloride releases were chemical complexes with chlor-alkali plants. Reporting from other countries is non-existent or incomplete. The European Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (E-PRTR) contains no reported emissions of carbon tetrachloride from chlorine plants in the European Union between 2012 and 2016. Manufacturers are required to report carbon tetrachloride releases in excess of 100 kg per year, however, European scientists tracking carbon tetrachloride emissions say the industry is likely not reporting emissions. A 2016 report estimated that the chlor-alkali industry worldwide was responsible for about 10,000 metric tons of unreported carbon tetrachloride releases, or about 40% of all unreported carbon tetrachloride releases.

- “Comments to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on the Scope of Its Risk Evaluation for the TSCA Work Plan Chemical: CARBON TETRACHLORIDE (CTC) CAS Reg. No. 56-23-5.” Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families; Environmental Health Strategy Center; Healthy Building Network, March 15, 2017.; “Common Product: XPS Insulation (Extruded Polystyrene).” Pharos Project. Accessed February 1, 2017. https://pharos.habitablefuture.org/common-products/2078867.; “Substitutes in Polystyrene: Extruded Boardstock and Billet.” United States Environmental Protection Agency: Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP). Accessed July 26, 2018. https://www.epa.gov/snap/substitutes-polystyrene-extruded-boardstock-and-billet.Global Warming Potential (GWP) defined — Certain gasses, commonly referred to as “greenhouse gasses”, have the ability to warm the earth by absorbing heat from the sun and trapping it in the atmosphere. Global warming potential is a relative measure of how much heat a given greenhouse gas will absorb in a given time period. GWP numbers are relative to carbon dioxide, which has a GWP of 1. The larger the GWP number, the more a gas warms the earth. Learn more about interpreting GWP numbers at www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/ understanding-global-warming-potentials.

- Liang, Q., P.A. Newman, and S. Reimann. “SPARC Report on the Mystery of Carbon Tetrachloride.” Stratosphere-troposphere Processes and their Role in Climate, July 2016. https://www.wcrp-climate.org/WCRP-publications/2016/SPARC_ Report7_2016.pdf.

- Vallette, Jim. “Chlorine and Building Materials: A Global Inventory of Production Technologies, Markets, and Pollution – Phase 1: Africa, The Americas, and Europe.” Healthy Building Network, July 2018. https://habitablefuture.org/resources/chlorine-building-materials-project-phase-1-africa-the-americas-and-europe/.

- Liang, Q., P.A. Newman, and S. Reimann. “SPARC Report on the Mystery of Carbon Tetrachloride.” Stratosphere-troposphere Processes and their Role in Climate, July 2016. https://www.wcrp-climate.org/WCRP-publications/2016/SPARC_ Report7_2016.pdf.

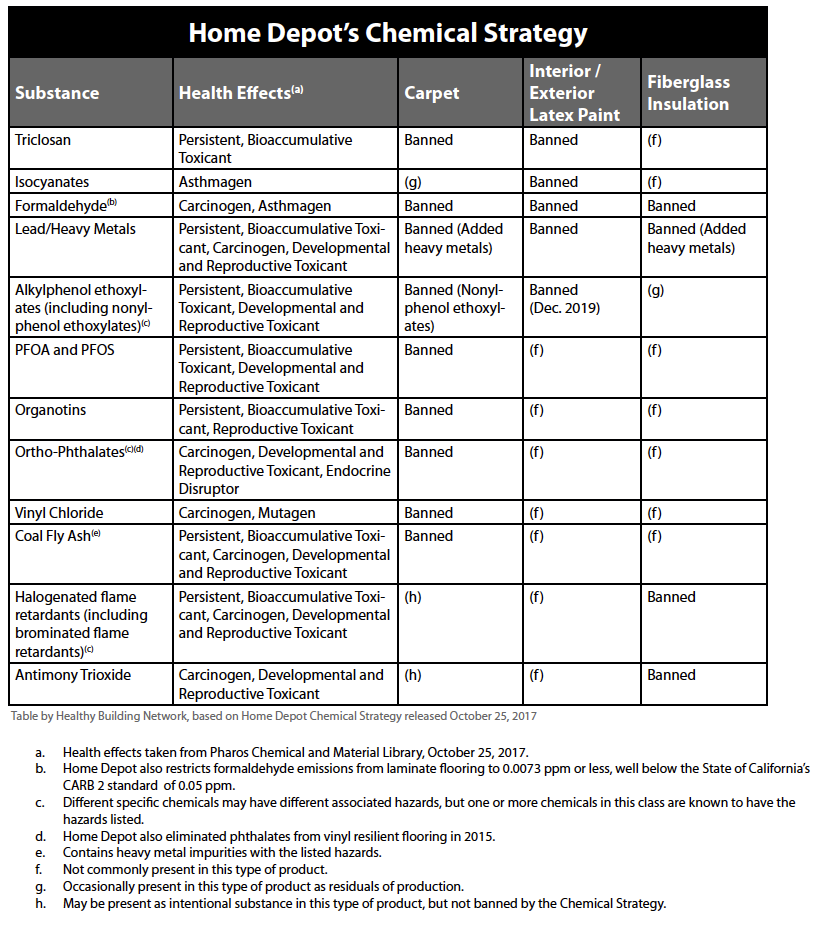

Home Depot today announced a chemical hazard avoidance policy that will prohibit numerous toxic chemicals in paints, carpeting, flooring and fiberglass insulation products.

The Home Depot Chemical Strategy, included in its 2017 Responsibility Report, targets a range of chemicals known or suspected to cause cancer, mimic and disrupt hormone systems, and impair brain function. The retailer’s policies, for certain product categories, far exceed the chemical restrictions of LEED and most product certifications in these categories. The world’s largest retailer of building products credited HBN’s “guidance on priority chemicals and innovation” as it adopted many of the recommendations made by HBN and other environmental health groups in a dialogue begun in 2014.

By applying its chemical strategy to all products in target categories, Home Depot makes important strides toward equity in the green building movement. It tracks many of the recommendations HBN provides to the affordable housing community in our HomeFree initiative. Because it impacts products at all price points, not just premium products and not just those that qualify for the retailer’s Eco-Options program, the policy ensures that all contractors and do-it-yourself customers get healthier products regardless of the brand purchased, and regardless of whether or not the product has been certified “green.” One of the qualifying products, a flat sheen paint, is the first “zero VOC” paint priced under $20 per gallon.[1] “We’re not just sourcing new healthier products, we are striving to improve our current assortment of the products we already sell,” Ron Jarvis, Home Depot Vice President of Merchandising and Sustainability, told HBN.

Home Depot’s most significant advances are in reducing toxic hazards in carpets and paints. The new carpet policy implements two major recommendations of HBN’s newest report, Eliminating Toxics In Carpet: Lessons For The Future of Recycling. published last week. As we reported, Shaw Industries – the country’s largest carpet manufacturer – recently stopped using fly ash from coal-fired power plants as filler. Today, Home Depot announced that fly ash, which contains toxic heavy metals, is “excluded from indoor wall-to-wall carpet in our U.S. and Canada stores.” Home Depot also announced its carpet does not contain several other chemicals that HBN has prioritized for elimination, including ortho-phthalates and organotins used in carpet backings.

Home Depot will also eliminate a class of toxic chemicals from paints called alkylphenol ethoxylates (APEOs). These chemicals, which are present even in low VOC paints, are surfactants, which help different types of material mix together well, and are coming under increased scrutiny as hormone disrupting chemicals with health effects ranging from breast cancer, reproductive disorders and obesity. They are mostly phased-out in Europe and Japan, but still common in the U.S., even though the EPA has identified over 200 “safer surfactants” to replace them.[2]

Today’s announcement is the next step on a long road that started with Home Depot’s 2015 move to eliminate phthalates from vinyl flooring. Much work lies ahead. For example, the company noted that it was not removing methylene chloride paint strippers from its shelves, a major objective of the national consumer campaign Mind The Store. The retailer’s hazard avoidance policy does not address some important problems even within the building product categories in its scope, and does not apply to many other high-impact building product categories. Regrettably, full public disclosure of all product ingredients is not required.

However, the hazard avoidance approach of the Home Depot Chemical Strategy signals fundamental, permanent and systemic improvement in the building products industry, and is a strong step towards health equity in building products. It leans toward a future when “healthy products” are not sold for a premium or as specialty items, and any product on the shelf meets the reasonable consumer expectations that it is healthy for people and our planet.

The Home Depot 2017 Responsibility Report can be found here:

https://corporate.homedepot.com/newsroom/infographic-2017-responsibility-report

SOURCES

- Glidden Premium flat sheen white begins at $17.97: https://www.homedepot.com/b/Paint-Paint-Colors/Glidden-Premium/Interior-Paint/N-5yc1vZcaw8Z55aZ1z0q3xf.

- While there are some paints available in the US that are free of these chemicals, including product lines from Benjamin Moore and Sherwin Williams. Home Depot is the first major paint seller to prohibit them in all formulations offered for sale, affecting most of the formulas sold today and all sales by December 2019.

Climate Change

Climate Change Health

Health Pollution

Pollution