READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORTYou may know the phrase, “you are what you eat.” There is a parallel concept when it comes to hazardous chemicals—you are what surrounds you!

Every day we come in contact with a large number of chemical products. Think of the last time you walked through a space being remodeled, or sat in a new car and thought “what’s that smell?” Your body notices that smell because a chemical or substance is interacting with the smell receptors in your nose. The same characteristics that allow it to interact with your nose could make those chemicals affect the body in other ways too—sometimes causing harm. The more invisible moments occur when sleeping on your mattress filled with flame retardants or using your personal care products while getting ready for work. Perhaps you work in a factory, as a contractor installing products, or some other job requiring direct contact with a variety of chemicals. The list (both visible and invisible) goes on and on. While a one-time exposure might not lead to health effects, a life-time of exposure and buildup to these chemicals can. More and more scientific evidence links these chemical exposures to diseases like cancer and diabetes, as well as developmental delays, reproductive health issues, and Autism Spectrum Disorder1.

There are three main exposure pathways: 1) inhalation – breathing in contaminated air, 2) ingestion – the inadvertent passing of dust or other chemical residues from hands to mouth, and 3) because our skin is like a sponge – absorption through dermal contact. According to the Environmental Working Group (EWG), babies still in the womb are exposed to more than 200 chemicals that pass from their mother through the umbilical cord2. This should make you wonder—what are the chemicals I may not realize are entering my body? There is a term used to describe the load of chemicals in the human body—body burden.

There’s what in my body?!

We sat down with Teresa McGrath, Healthy Building Network’s (HBN) Chief Research Officer earlier this year to talk about urine, specifically hers. Earlier this year, Teresa participated in a study on chemical body burden led by Silent Spring Institute. Teresa is an avid runner who’s completed marathons and loves snacking on fresh vegetables from her local farmers market. She is one of the healthiest and most health conscious individuals on our team and we were very interested in learning her results.

The study, titled Detox Me Now, included approximately 350 participants. Teresa submitted her urinary sample for testing 15 chemicals, including3:

- Chlorinated phenols

- Bisphenols

- Alkylphenol ethoxylates (found in paints)

- UV filters

- Parabens (commonly used in makeup products as a preservative)

- Antimicrobials

Teresa’s Results

Her study results detected seven of the 15 chemicals tested in her urine sample. There are a couple of basic rules to follow when it comes to interpreting biomonitoring results. The first is that a higher number is not always a reason for concern4. And the second is that from a hazard perspective, not all chemicals are the same5. Each chemical possesses its own set of health effects at different dosages and routes of exposure6.

Regrettable Substitutions

During our conversation, Teresa McGrath offered a particularly interesting study finding—her differing bisphenol results particularly when compared to the study median and the US median.

This study tested for two bisphenols, bisphenol-A (BPA) and bisphenol-S (BPS). If BPA sounds familiar, that is probably because this is the much-talked about ingredient commonly used in polycarbonate plastic bottles, lining for food and beverage cans and thermal paper receipts. It can cause endocrine disruption.7,8 BPS is a common replacement for BPA in many thermal applications including paper receipts and plastics and has similar health concerns as BPA9. Teresa’s results for BPA were lower than the median for the Silent Spring Detox Me Now study participants AND lower than the US median10. However, her BPS levels were greater than her BPA levels, greater than the median for the Silent Spring Detox Me Now study participants AND greater than the US median11. This is illustrated in the following graphic from her study report.

The report offers two possible explanations:

- Teresa successfully avoids BPA by choosing products that are BPA-free and unwittingly preferring products that use BPS, the common BPA alternative.

- The timing of the studies coincided with an industry-wide shift from BPA to other bisphenols, including BPS. The US median data (NHANES) was collected between 2013 and 2014, while the Detox Me Action Kit test samples are dated 2016 to 2018.

By simply purchasing BPA-free products, one can reduce exposure to BPA. However, industries continue to choose “regrettable substitutions” or replacing one chemical with another similar chemical and/or a chemical with unknown health effects. Much of our work focuses on helping industries avoid regrettable substitutions.

Here’s how you can decrease your exposure to toxic chemicals.

Wrapping up our conversation with Teresa, we briefly discussed the overall study implications and additional survey results. Compared to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted by the Centers for Disease Control, participants of this study possessed lower chemical burdens than most people in the United States. One explanation for this may be attributed to 43 percent of participants self-reporting that they avoid products with parabens, BPA, triclosan, and fragrance, and an additional 40 percent reported avoiding two or three of those chemicals.

So, how can you reduce your exposure? Silent Spring offers some ideas, including:

- Asking your favorite brands and stores to choose safer chemicals

- Avoiding personal care products and cosmetics that list parabens as ingredients

- Learning which personal care and cosmetics companies avoid harmful chemicals

You can also download their Detox Me Now App for more tips.

Biomonitoring studies similar to Silent Spring’s are springing up in recent years, as have articles about their results, such as this story in the Guardian. For only a few hundred dollars, consumers can know the exact chemical composition of their bodies. For those who find sample submission undesirable, HBN has added a new feature in our Pharos platform that provides links to biomonitoring databases with information on chemicals identified in the bodies of individuals from different regional communities. The results continually shed light on the need for greater industrial transparency and a transition to safer products.

This is one more example of why HBN passionately paves the way to safer products, offering recommended alternatives from expert chemical analysis and by fostering collaborative industry partnerships.

SOURCES

- Kim et al., “Exposure to pesticides and the associated human health effects.” Science of the Total Environment 575, (2017). 525-535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.009

- Environmental Working Group, “ Body Burden: The Pollution in Newborns.” Environmental Working Group, last modified July 14, 2005, https://www.ewg.org/research/body-burden-pollution-newborns.

- Fransway et al.. “Parabens.” Dermatitis 30, 1 (2019). 3-31. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000429

- Casarett, Louis J., John Doull, and Curtis D. Klaassen. 2001. Casarett and Doull’s toxicology: the basic science of poisons. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Pub. Division.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- National Toxicology Program, “Bisphenol A (BPA),” National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, last modified May 23, 2019, https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/sya-bpa/index.cfm.

- Silent Spring Institute, “Our Science”, Silent Spring Institute, accessed September 17, 2019, https://libanswers.snhu.edu/faq/48009.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. The “US median” results in this article refer to the NHANES study. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a program established in the 1960s run by the Centers for Disease Control that tracks the health of adults and children in the United States. NHANES tested surveyed individuals for many of the Detox Me Now Action Kit chemicals. The most recent NHANES data, from 2013-2014, were used as a nationally representative estimate of exposure in the United States.

- Ibid.

Current climate action plans are bold, they are necessary, they feel impossible, and they are coming into the consciousness of all concerned (and unconcerned), decades after the early reports should have been taken seriously.

At this point, there is an urgency because people are now experiencing the effects of a warming planet:storms, fires, rising tides, health impacts from warmer temperatures, and more.

To date, climate plans have focused on strategies related to renewable and clean energy, greater efficiency, emissions reduction, etc., especially as it relates to building operations and transportation. However, that is only one side of the (enormous) coin, and it misses key opportunities on the opposite side. It is akin to making the decision to improve your health by incorporating an exercise plan, but continuing a diet of nutritionally deficient and unhealthy foods. You will only get so far, and your dedication to exercise will be undercut by your fast food burgers and supersized fries.

The other side of the coin? If building and transportation energy and emissions reduction is “heads,” what could be so immense that it fills the flipside? The “tails” of that coin is the vast quantities of products being produced, its emissions and pollution, and the need for toxic chemical mitigation. The missing piece in effective climate mitigation and improved global health is a toxic-free, recyclable product cycle (low-waste and closed-loop).

The Link Between Emissions, Circular Economy, and Chemicals

Climate plans must include Circular Economy strategies, and a circular economy is possible only if safe chemistries are used as inputs to products.1 The Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s (EMF) September 2019 report: Completing the Picture: How the Circular Economy Tackles Climate Change makes the case that we must address the product cycle as a core part of climate action plans.2 According to the report, “to date, efforts to tackle the [climate] crisis have focused on a transition to renewable energy, complemented by energy efficiency. Though crucial and wholly consistent with a circular economy, these measures can only address 55% of emissions. The remaining 45% comes from producing the cars, clothes, food, and other products we use every day.”

There is more than just emissions that makes the product cycle a critical component of an effective climate strategy. At Habitable, our research shows that there is a related and similar urgency in addressing severe health crises, impacting marginalized communities the hardest, but also now affecting a larger population of people. Our plans—starting with transparency (requesting manufacturers provide the public with a complete list of product ingredients); full testing of all chemicals for human and environmental health impacts; and innovation to new, “green” (safer) chemicals—are bold, necessary and they also feel impossible.

The EMF Completing the Picture report makes the case that we must fundamentally change how our products are made. A key recommendation in reducing emissions is to “design out waste and pollution.” To be even more precise, designing the toxics out of our products is key to eliminating waste and creating the safe and circular economy that is the cornerstone of any climate solution, an inextricable element in human and environmental health.

A companion report by Google, in partnership with EMF, The Role of Safe Chemistry and Healthy Materials in Unlocking the Circular Economy, emphasizes that toxic chemical mitigation is a precursor to a circular economy. It suggests that “the short- and long-term impacts of these new chemical substances has lagged behind the drive to create new molecules and materials. We can see the consequences around us, including ‘sick building syndrome,’ flame retardants accumulating in human breast milk and being passed along to newborns, or entire city populations toxified from local environmental exposures and contaminated drinking water.” The authors of the report put out a challenge to the world’s chemists and material scientists to not only develop molecules and materials that achieve a performance or aesthetic outcome, but also to ensure that these substances are safe for people and the environment, can be cycled and used to create future products, and retain economic value throughout its lifecycle. Safer chemistry is the key to unlock a circular economy.

The health impacts related to our petrochemical and hazardous chemical-dependent product economy are real, but are often unseen or unrecognized. Globally declining sperm counts and reproductive disorders are linked to chemicals in our plastics,3 and a growing library of peer-reviewed studies link today’s epidemic health issues—cancer, diabetes, obesity, asthma and autism—to endocrine-disrupting and neurotoxic chemicals.4 These data often take a back seat to the climate crisis in our headlines, but they too are growing worse and in need of bold action.

“Better Living Through Chemistry” vs Better Chemistry for Healthier Living

DuPont (and other chemical companies) did not get it right with the blanket phrase, “Better Living Through Chemistry.”

Has there been some great progress and benefits from innovative products that use new chemistries and materials?—yes, of course. That said, a significant lack of understanding of the toxicological effects on humans and the environment have come at great cost. We are finding that the tradeoffs are severe—though today, like the early science on climate change, most people are unaware of this silent epidemic, and tend to accept the rise in cancer, autism, fertility problems, and developmental issues in children, as only an unfortunate part of life—they or their loved ones just pulled a short straw, bad luck.

In 1970, the U.S. produced 50 million tons of synthetic chemicals.5 In 1995, the number tripled to 150 million tons, and today, that number continues to increase.6 Very few of the tens of thousands of chemicals in the marketplace are fully tested for health hazards, and details on human exposure to these chemicals is limited.7 We are exposed to these chemicals every day, in varying quantities and combinations. Over a lifetime, the small exposures add up. Science-based predictions of health outcomes from long-term exposure continue to emerge,8 but add on the component of a warming climate and a new layer of concern is revealing itself.9

Both/And Solution

The best climate plans are holistic. They recognize and include strategies from both the clean and renewable energy effort and safe and circular product cycle. The threats and impacts of climate change and toxic chemicals are synergistic, as are the solutions. They must be tethered in order to be effective. In fact, ignoring the chemical/material side of the coin will undermine progress on climate and energy solutions.

We know better, and we can do better.

As energy efficiency and renewable energy gains reduce the carbon footprint of the transportation and building operations sectors, addressing product production assumes an even greater importance. Successfully addressing climate change requires a revolutionary change in how we design and manufacture materials, towards a circular, closed-loop economy. But materials cannot flow effectively in a closed-loop if they are contaminated with toxic chemicals. Safe first, and then circular is possible.

The urgency to mitigate toxics must be on par with the urgency for clean and renewable energy – they are two sides of the same coin. Failing to recognize this, and create holistic, compatible solutions, will undermine our goals to manage climate change and improve global health.

SOURCES

- “What Is a Circular Economy? | Ellen MacArthur Foundation,” accessed November 25, 2019, https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/concept.

- “Circular Economy Reports & Publications From The Ellen MacArthur Foundation,” accessed November 25, 2019, https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications.

- Teresa Carr, “Sperm Counts Are on the Decline – Could Plastics Be to Blame?,” The Guardian, May 24, 2019, sec. US news, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/may/24/toxic-america-sperm-counts-plastics-research.

- Naoko OHTANI et al., “Adverse Effects of Maternal Exposure to Bisphenol F on the Anxiety- and Depression-like Behavior of Offspring,” The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 79, no. 2 (February 2017): 432–39, https://doi.org/10.1292/jvms.16-0502.

- Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Practice, and Medicine.

- Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Practice, and Medicine.

More than 15% of North Americans report an unusual hypersensitivity to common chemical products such as those used in new-home construction. Another 40% may have mild symptoms of which they’re unaware.

This book explores the journey of designing and building a prototype healthy house, aiming to provide a sanctuary for healing and addressing environmental hypersensitivity, serving as a comprehensive guide for those interested in healthier approaches to design, construction, or remodeling.

Circular design encourages us to rethink business models and how we make products, and to consider the systems surrounding them. But we also need to think about the materials we use – and the chemistry behind them.

To create a truly sustainable circular economy, we must know what’s in the materials and products we choose, and those choices should focus on optimized chemistry for human and environmental health. Only then will we have the building blocks for a circular economy.

Chemistry is an important part of the value stream.

A circular economy is fueled by the creation and retention of value. By keeping material streams as pure as possible from the beginning and through the entire use cycle, the full value of a material is retained. Value retention is key to activating the systems that make the circular economy function, including the incentive for manufacturers to take back products because they have value and the motivation for entrepreneurs to create robust secondary markets.

Not all materials are fit for a circular economy, however. When they contain chemicals that are hazardous for humans or the environment, they provide little to no value in supporting circularity. Fortunately there are ways to choose materials that are safe AND circular so you can build a better offering for your users and introduce valuable inputs for a sustainable economy.

New Safe and Circular learning modules provide an excellent place to start.

To help designers, entrepreneurs, and innovators make positive materials choices and integrate better chemistry into the design process from the very start, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and the Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Institute (C2C PII) have released a new series of advanced learning modules as part of the foundation’s Circular Design Guide, which was co-created with IDEO.

You’ll find them in the Methods section of the guide (scroll to the “Advanced” section), which aims to fuel design thinking for the circular economy by challenging traditional design methods, delivering new approaches, and introducing users to circular economy concepts as well as techniques updated for this new economic framework.

The new modules include:

- Materials Journey Mapping: Explore how materials choices can influence a design to fit a circular economy.

- Product Redesign Workshop: Explore the implications of safe and circular material strategies on the design process through a redesign workshop.

- Material Selection: Choose the right materials for your new circular design.

- Moving Forward with Materials: Explore the next steps for making safe and circular material choices a driver for innovation in your design process.

Check out Safe & Circular by Design: Making Positive Material Choices, a podcast hosted by Emma Fromberg from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and featuring Stacy Glass, director of ChemFORWARD, alongside other leaders in the safe and circular movement.

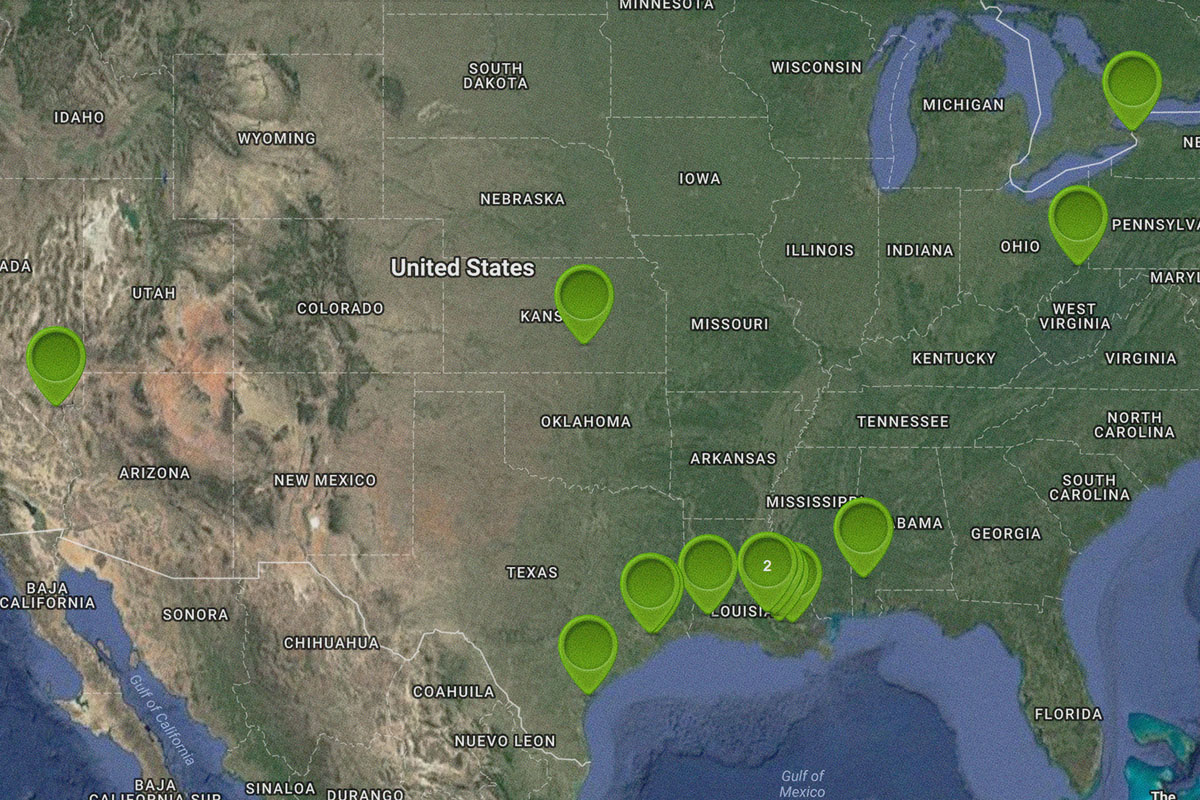

While attending a 2018 meeting of U.S. EPA’s National Environmental Justice Advisory Council (NEJAC) in Boston, I heard the testimony of Delma and Christine Bennet. They live in Mossville, LA, amidst what is likely the nation’s largest concentration of PVC (polyvinyl chloride) manufacturing facilities. I was there to present the findings of HBN’s inventory of pollution associated with the chlorine/PVC supply chain.

Our study found, among other things, that the Gulf Coast region (which includes Mossville) is home to nine facilities that use outmoded asbestos technology, and home also to some of the industry’s worst polluters: Five of the six largest emitters of dioxins––a long lasting, extremely toxic family of hazardous waste that causes cancer and many other health impacts, are located there. The Bennets reminded the EPA that according to studies by a division of the Centers for Disease Control, Mossville residents have three times higher levels of dioxin in their blood than average Americans, and the dioxin levels found in their yards and attic dust exceed regulatory standards typically used for toxic waste remediations of industrial sites. Even the vegetables in their gardens tested positive for dioxin.

When I think about why we fight so hard to exclude PVC from any palette of green, healthy, or sustainable building materials, I think first of people like Delma and Christine. I then think about the many non-profits, government agencies, and private enterprises dedicated to recycling. Way back in the 1990’s, the industry Association of Plastic Recyclers declared PVC a contaminant to the recycling stream. A generation later, a 2016 study by the Circular Economy evangelist Ellen MacArthur Foundation called out PVC packaging for global phase-out, citing low recycling rates and chemical hazard concerns. Much of the concern about PVC packaging is driven by worries about ocean pollution. HBN’s study found that at least one U.S. PVC manufacturer is routinely dumping tons of PVC pellets into local waterways and refusing to stop even after being ordered to do so by the state of Texas.

The list goes on. Our report documents the types of industrial pollution in addition to dioxin that could be reduced or avoided by a switch to more recyclable plastics that are not made with the chlorine that is an essential ingredient of PVC, including ozone depleting and potent global warming gasses. HBN’s earlier studies have documented the hazards posed by legacy pollutants that are returning to our consumer products in recycled PVC content––heavy metals such as lead, and endocrine-disrupting plasticizers known as phthalates.

There is a better way.

There is virtually no use of PVC in building products that could not be replaced with another plastic or other material. Indeed, from siding, to wallpaper, to window frames, PVC has displaced materials that are more recyclable, such as aluminum and paper. Because the industry is not held accountable for the environmental health damages wrought in places like Mossville, PVC has artificially low costs that present barriers to entry, or inhibit market expansion of less hazardous, more sustainable alternatives.

That is why PVC should not be part of any building, or any building rating system, that claims to advance environmental and health objectives. It’s not green. It’s not healthy. It’s not sustainable. It’s just cheap––for us. Because folks like Delma and Christine Bennet pay the true cost.

Know Better

Learn more about the implications of chlorine as a feedstock in plastics in HBN’s Chlorine and Building Materials report.

As noted in Healthy Building Network’s(HBN) Chlorine and Building Materials report, chlorine production is a major source of releases of carbon tetrachloride, a potent global warming and ozone depleting gas as well as a carcinogen.

As the report reminds us, it’s important to consider not only the use-phase impacts of building products, but the entire life cycle, including primary chemical production that’s several steps back from final product manufacture.

Blowing agents are used in plastic foam insulation to create the foam structure and also contribute to the insulative properties. Over the years, manufacturers have cycled through a range of fluorocarbons as each prior class is phased out due to environmental concerns – from ozone depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) to less ozone depleting hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) to the non-ozone depleting but high global warming potential hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) currently common in many types of foam insulation. Manufacturers have now begun the latest shift to next generation, low global warming potential hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs). For extruded polystyrene (XPS), this translates to a shift from commonly used HFC-134a with a global warming potential (GWP) of 1,430 to HFO-1234ze with a GWP of six.2

The summary of these chemical transitions only tells part of the story. While HFOs do not directly deplete the ozone layer or significantly contribute to global warming, many HFOs use carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) as a chemical feedstock. This includes HFO-1234ze, the replacement for HFC-134a (which does not use CCl4) in many applications.3

How is it that this ozone depleting substance is still in use? Many uses of carbon tetrachloride were phased out in 1995, under the terms of the Montreal Protocol to protect the ozone layer. But the Montreal Protocol phase-outs exempted the use of CCl4 as a chemical feedstock, under the assumption that emissions would be minor.4 However, carbon tetrachloride “is not decreasing in the atmosphere as rapidly as expected” based on its known lifetime and emissions, according to a 2016 report on the Mystery of Carbon Tetrachloride. The authors of this report concluded that emissions of carbon tetrachloride during its production, and fugitive emissions from its use as a chemical feedstock, have been significantly unreported and underestimated.5

Production of carbon tetrachloride is likely to increase as industry replaces HFC blowing agents (and refrigerants), most of which aren’t produced with carbon tetrachloride, with HFOs that do use CCl4 as a feedstock.[6] With increased production and use of carbon tetrachloride, increased emissions are expected – and that’s bad news for the earth’s recovering ozone layer.

We recommend against the use of plastic foam insulation whenever possible, but if you do use it, some products are available that use other, less impactful, blowing agents, including hydrocarbons and water. For more recommendations about preferable insulation from a health hazard perspective, review our product guidance at informed.habitablefuture.org.

SOURCES

- According to US Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) data from 2012 to 2015, half of the 10 leading sources of carbon tetrachloride releases were chemical complexes with chlor-alkali plants. Reporting from other countries is non-existent or incomplete. The European Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (E-PRTR) contains no reported emissions of carbon tetrachloride from chlorine plants in the European Union between 2012 and 2016. Manufacturers are required to report carbon tetrachloride releases in excess of 100 kg per year, however, European scientists tracking carbon tetrachloride emissions say the industry is likely not reporting emissions. A 2016 report estimated that the chlor-alkali industry worldwide was responsible for about 10,000 metric tons of unreported carbon tetrachloride releases, or about 40% of all unreported carbon tetrachloride releases.

- “Comments to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on the Scope of Its Risk Evaluation for the TSCA Work Plan Chemical: CARBON TETRACHLORIDE (CTC) CAS Reg. No. 56-23-5.” Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families; Environmental Health Strategy Center; Healthy Building Network, March 15, 2017.; “Common Product: XPS Insulation (Extruded Polystyrene).” Pharos Project. Accessed February 1, 2017. https://pharos.habitablefuture.org/common-products/2078867.; “Substitutes in Polystyrene: Extruded Boardstock and Billet.” United States Environmental Protection Agency: Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP). Accessed July 26, 2018. https://www.epa.gov/snap/substitutes-polystyrene-extruded-boardstock-and-billet.Global Warming Potential (GWP) defined — Certain gasses, commonly referred to as “greenhouse gasses”, have the ability to warm the earth by absorbing heat from the sun and trapping it in the atmosphere. Global warming potential is a relative measure of how much heat a given greenhouse gas will absorb in a given time period. GWP numbers are relative to carbon dioxide, which has a GWP of 1. The larger the GWP number, the more a gas warms the earth. Learn more about interpreting GWP numbers at www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/ understanding-global-warming-potentials.

- Liang, Q., P.A. Newman, and S. Reimann. “SPARC Report on the Mystery of Carbon Tetrachloride.” Stratosphere-troposphere Processes and their Role in Climate, July 2016. https://www.wcrp-climate.org/WCRP-publications/2016/SPARC_ Report7_2016.pdf.

- Vallette, Jim. “Chlorine and Building Materials: A Global Inventory of Production Technologies, Markets, and Pollution – Phase 1: Africa, The Americas, and Europe.” Healthy Building Network, July 2018. https://habitablefuture.org/resources/chlorine-building-materials-project-phase-1-africa-the-americas-and-europe/.

- Liang, Q., P.A. Newman, and S. Reimann. “SPARC Report on the Mystery of Carbon Tetrachloride.” Stratosphere-troposphere Processes and their Role in Climate, July 2016. https://www.wcrp-climate.org/WCRP-publications/2016/SPARC_ Report7_2016.pdf.

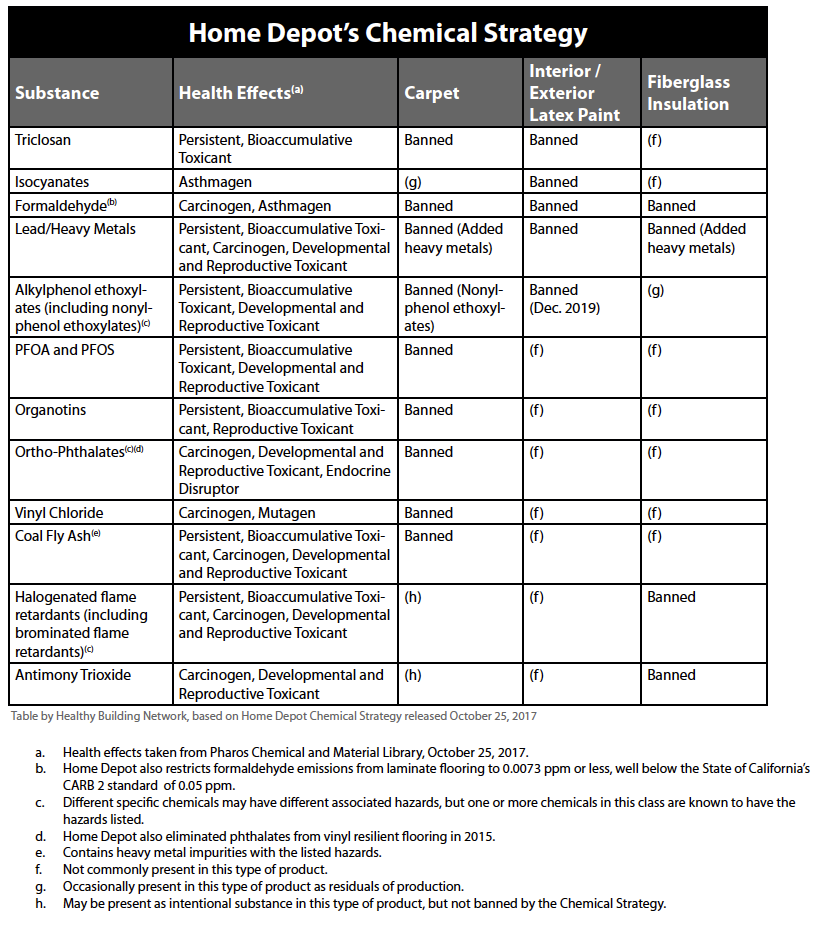

Home Depot today announced a chemical hazard avoidance policy that will prohibit numerous toxic chemicals in paints, carpeting, flooring and fiberglass insulation products.

The Home Depot Chemical Strategy, included in its 2017 Responsibility Report, targets a range of chemicals known or suspected to cause cancer, mimic and disrupt hormone systems, and impair brain function. The retailer’s policies, for certain product categories, far exceed the chemical restrictions of LEED and most product certifications in these categories. The world’s largest retailer of building products credited HBN’s “guidance on priority chemicals and innovation” as it adopted many of the recommendations made by HBN and other environmental health groups in a dialogue begun in 2014.

By applying its chemical strategy to all products in target categories, Home Depot makes important strides toward equity in the green building movement. It tracks many of the recommendations HBN provides to the affordable housing community in our HomeFree initiative. Because it impacts products at all price points, not just premium products and not just those that qualify for the retailer’s Eco-Options program, the policy ensures that all contractors and do-it-yourself customers get healthier products regardless of the brand purchased, and regardless of whether or not the product has been certified “green.” One of the qualifying products, a flat sheen paint, is the first “zero VOC” paint priced under $20 per gallon.[1] “We’re not just sourcing new healthier products, we are striving to improve our current assortment of the products we already sell,” Ron Jarvis, Home Depot Vice President of Merchandising and Sustainability, told HBN.

Home Depot’s most significant advances are in reducing toxic hazards in carpets and paints. The new carpet policy implements two major recommendations of HBN’s newest report, Eliminating Toxics In Carpet: Lessons For The Future of Recycling. published last week. As we reported, Shaw Industries – the country’s largest carpet manufacturer – recently stopped using fly ash from coal-fired power plants as filler. Today, Home Depot announced that fly ash, which contains toxic heavy metals, is “excluded from indoor wall-to-wall carpet in our U.S. and Canada stores.” Home Depot also announced its carpet does not contain several other chemicals that HBN has prioritized for elimination, including ortho-phthalates and organotins used in carpet backings.

Home Depot will also eliminate a class of toxic chemicals from paints called alkylphenol ethoxylates (APEOs). These chemicals, which are present even in low VOC paints, are surfactants, which help different types of material mix together well, and are coming under increased scrutiny as hormone disrupting chemicals with health effects ranging from breast cancer, reproductive disorders and obesity. They are mostly phased-out in Europe and Japan, but still common in the U.S., even though the EPA has identified over 200 “safer surfactants” to replace them.[2]

Today’s announcement is the next step on a long road that started with Home Depot’s 2015 move to eliminate phthalates from vinyl flooring. Much work lies ahead. For example, the company noted that it was not removing methylene chloride paint strippers from its shelves, a major objective of the national consumer campaign Mind The Store. The retailer’s hazard avoidance policy does not address some important problems even within the building product categories in its scope, and does not apply to many other high-impact building product categories. Regrettably, full public disclosure of all product ingredients is not required.

However, the hazard avoidance approach of the Home Depot Chemical Strategy signals fundamental, permanent and systemic improvement in the building products industry, and is a strong step towards health equity in building products. It leans toward a future when “healthy products” are not sold for a premium or as specialty items, and any product on the shelf meets the reasonable consumer expectations that it is healthy for people and our planet.

The Home Depot 2017 Responsibility Report can be found here:

https://corporate.homedepot.com/newsroom/infographic-2017-responsibility-report

SOURCES

- Glidden Premium flat sheen white begins at $17.97: https://www.homedepot.com/b/Paint-Paint-Colors/Glidden-Premium/Interior-Paint/N-5yc1vZcaw8Z55aZ1z0q3xf.

- While there are some paints available in the US that are free of these chemicals, including product lines from Benjamin Moore and Sherwin Williams. Home Depot is the first major paint seller to prohibit them in all formulations offered for sale, affecting most of the formulas sold today and all sales by December 2019.

Research from Healthy Building Network (HBN) documents how vinyl building products, also known as PVC or polyvinylchloride plastic, are the number one driver of asbestos use in the US.

The vinyl/asbestos connection stems from the fact that PVC production is the largest single use for industrial chlorine, and chlorine production is the largest single consumer of asbestos in the US. [1] More than 70% of PVC is used in building and construction applications – pipes, flooring, window frames, siding, wall coverings and membrane roofing. [2] This makes the building and construction industry the single largest product sector consuming chlorine, bearing sizeable responsibility for the ongoing demand for asbestos. [3]

Despite the existence of asbestos (and mercury) free chlorine production methods, the PVC industry has positioned itself at the vanguard of industry efforts to frustrate stronger asbestos regulation. According to Mike Belliveau, the Executive Director of the Environmental Health Strategy Center and a senior advisor to Safer Chemicals Healthy Families coalition, “The PVC market has spurred chemical industry lobbyists to urge the Trump Administration to exempt their use of deadly asbestos from future restrictions.” The last time the vinyl industry positioned themselves so publicly on the other side of common sense, they were defending the use of lead in children’s vinyl lunch boxes.

Among HBN’s Findings:

- The U.S. chlor-alkali industry (Olin/Dow, Occidental, and Westlake/Axiall [4]) consumed 88% of asbestos imports in 2014, and all asbestos imports in 2016.

- Three U.S. chemical companies are importing 1.2 million pounds of asbestos per year for use in 15 chlor-alkali plants. PVC used in building products requires an estimated 250,000 pounds of imported asbestos per year.

- Asbestos miners in Minaçu, Brazil, are literally dying to prop up the U.S. chemical and PVC building product industries’ reliance on asbestos. Dozens of asbestos baggers are dying or have died of asbestos related diseases, according to local reports. [5] Overall, Brazil exports over 13,000 bags of asbestos each year to the U.S. chlorine industry.

- Occidental Chemical imported 900,000 pounds of asbestos from Oct. 2013 through 2015, but apparently failed to report those imports to the EPA in possible violation of the Chemical Data Reporting rule as required under TSCA.

- Asbestos imports by Occidental Chemical and Olin Corporation more than doubled from 2015 to 2016, perhaps indicating a stockpiling of asbestos in anticipation of further restrictions on mining in Brazil or use in the U.S.

- Russia shipped asbestos to Dow in 2014 and to Olin in 2016 (when Olin took over Dow’s U.S. chlor-alkali plants). If the mine in Brazil closes, the U.S. chlor-alkali industry’s backup plan is the massive mine in Asbest, Russia.

The health hazards of asbestos exposure, painful and deadly lung diseases including cancer, are clear. Green building professionals do not have to wait. Do your part to prevent asbestos-related diseases here and abroad. Don’t specify vinyl building products.

SOURCES

1. In the US more than half of chlorine is produced using asbestos, despite the availability of an alternative production method that does not require either asbestos or mercury.

2. http://www.vinylinfo.org/vinyl/uses

3. According to IHS Markit, “A majority of chlor-alkali capacity is built to supply feedstock for ethylene dichloride (EDC) production. EDC is then used to make vinyl chloride (VCM) and subsequently used to manufacture polyvinyl chloride (PVC). This chain, EDC to VCM to PVC, is normally called the vinyl chain. PVC demand correlates closely with construction spending, therefore, it can be concluded that chlorine consumption and production are driven by the construction industry. Hence, chlorine consumption growth depends on the growth of the global economy, since a country will spend more on construction if it has a healthy gross domestic product.” (IHS Markit. “Chemical Economics Handbook: Chlorine/Sodium Hydroxide (Chlor-Alkali),” December 2014. https://www.ihs.com/products/chlorine-sodium-chemical-economics-handbook.html)

4. Fifteen chlor-alkali plants last reported to be using asbestos diaphragms include, in order of estimated chlorine capacity:

-

- Olin (formerly Dow), Freeport, Tex. (3,158,000 tons per year)

- Westlake (formerly Axiall), Lake Charles, La. (1,100,000 tpy)

- Olin, Plaquemine, La. (1,068,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Ingleside/Corpus Christi, Tex. (668,000 tpy)

- Occidental, La Porte, Tex. (580,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Hahnville/Taft, La. (567,000 tpy)

- Olin, McIntosh, Ala. (468,000 tpy)

- Westlake, Plaquemine, La. (410,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Convent, La. (389,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Niagara Falls, N.Y. (336,000 tpy)

- Westlake, Natrium/New Martinsville, W.Va. (297,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Geismar, La. (273,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Wichita, Kans. (182,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Deer Park, Tex. (162,500 tpy)

- Olin, Henderson, Nev. (153,000 tpy)

5. Carpentier, Steve. “Minaçu, a cidade que respira o amianto.” CartaCapital, May 21, 2013. http://www.cartacapital.com.br/sustentabilidade/minacu-a-cidade-que-respira-o-amianto-8717.html

When one waste disposal option closes, another inevitably opens.

A half-century ago, the federal government started regulating solid wastes and preventing rampant dumping in the woods, ocean, and unlined dumps. Then the so-called Not-In-My-Backyard (NIMBY) movement of the 1970s and 1980s prevented scores of landfills and incinerators from being permitted across the country, just as existing disposal sites were reaching capacity. There were also spectacular failures at waste sites that made headlines. Coal ash ponds failed, releasing contaminated waste into rivers and drinking water. Giant piles of tires caught on fire, and came to symbolize the crisis of growing piles of waste.

In response, environmental agencies partnered with waste generators like the coal power and tire industries to find ways to reduce the amount of their wastes going to landfills. The US Environmental Protection Agency developed an option called “beneficial use,” in which these wastes could be diverted to build roads, fill old mines, and turn wastelands into golf courses. Some of these “beneficial uses” hit literally close to home; coal waste has been diverted into wallboard and carpet backing, tires into flooring, and contaminated soils into our own backyards, without any regulation.

In two articles, we describe the impacts of this waste management strategy.

“On Tire Wastes in Playgrounds” reveals how chopped up tire mulch is becoming as common as dirt in playgrounds, and why government health agencies are beginning to take action to protect children from exposure to toxic substances in the rubber waste, like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and lead.

“Filled with Uncertainty: Toxic Dirt in Building & Construction” examines the unregulated dirt trade. Our research found that soil and coal ash contaminated with neurotoxic substances have become commonplace construction materials, from structural fill to flower bed topsoil. Contaminated material is often sold as “clean fill” by untrustworthy companies. With no tracking in place, building owners have no idea, and probably don’t think to ask, where their fill is coming from.

Waste has a way of finding the path of least resistance. A void of oversight coupled with numerous government and private sector incentives promoting the use of unregulated recycled content leaves it to responsible architects, designers, contractors and building owners to increase scrutiny of this vast diversion of wastes into our homes, schools, playgrounds and places of business. In the absence of political will, building owners and residents are left to protect themselves. We hope these articles will lead developers, especially of residential areas and playgrounds, to start asking more questions of dirt and fill contractors, beginning with: where did your materials come from, and have they been tested for toxic contaminants?

Many years after Kermit told us of the difficulty of being green, a friend put it another way. “Penny, it’s hard to be you.” She wasn’t slamming me but rather commenting on the burden of being knowledgeable – an appreciation of sorts.

Here’s what happened. While shopping in a grocery store my friend reached for a can of soup. I advised her instead to buy soup packaged in glass containers or boxes because of the bisphenol-A, or BPA, that is widely used in the linings of metal cans.

BPA, an endocrine disruptor, has been linked to an increased risk of cancer, birth defects, diabetes and other health threats. After a decade of research that convinced many retailers to remove BPA containing baby bottles and other plastic food containers from their shelves, a new study from researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health reported large increases in BPA levels in humans after eating just modest amounts of canned soup.

The results of this study surprised the researchers and will undoubtedly lead to further investigation. (Side note: Campbell Soup, the world’s largest soup maker announced it will soon stop using BPA in the linings of its cans.) And it’s not just soup cans. BPA and other endocrine disruptors are found in many products – thermal paper receipts, dental sealants, plastic water bottles and yes, building materials.

Typically they are found in epoxy-based products such as coatings, sealers, adhesives and fillers. As designers and specifiers it is our responsibility to find safer alternatives for BPA-containing products. Low-VOC water-based paints, for example, are BPA-free. But how do you know, and how do you know you’re supposed to know?

My point is this: it’s hard being me and it’s hard being you. I have plenty of cans in my pantry, some of them surely containing BPA in the liners. But just as I can choose to limit the number of canned foods I buy or search for those that are safer, so can we purposely and stridently refuse to specify materials with BPA and other known toxins into our projects.

There is a Chinese proverb that says, if we do not change our direction, we are likely to end up where we are headed. When ignorance ends, negligence begins and its antidote is responsibility. Making the choice to educate ourselves and then act on our newfound knowledge is the ethical obligation of every one of us.

Health

Health Climate Change

Climate Change Pollution

Pollution