Policy Brief + Recommendations

Policy Brief + RecommendationsIf we are to have any chance of addressing the global plastics crisis, Polyvinyl Chloride plastic (PVC) also known as vinyl, has got to go.

It cannot be produced sustainably or equitably. It cannot be “optimized.” It cannot be recycled. It will never find a place in a circular economy, and it makes it harder to achieve circularity with other materials, including other plastics.

There are three reasons for this: technical, economic, and behavioral. The inherent qualities of PVC and its cousin, CPVC, make it among the most technologically challenging plastics to recycle. Like most plastics, PVC is made with fossil fuel feedstocks. Unlike other plastics, PVC/vinyl also contains substantial amounts of chlorine, upwards of 40%. This is the C in PVC, and this chlorine content adds an additional layer of negative impacts to the earth and its people, social inequity, and an impediment to recycling that cannot be overcome. Recyclers consider it a contaminant to other plastic feedstock streams.1 It mucks up the machines and the already perilous economics of plastics recycling.

There is an emerging global consensus on this point, albeit euphemistically stated. The Ellen MacArthur New Plastics Economy Project consists of representatives from the world’s largest plastic makers and users, along with governments, academics, and NGOs. In 2017 it reached the conclusion that PVC was an “uncommon” plastic that was unlikely to be recycled and should be avoided in favor of other more recyclable packaging materials.2 “Uncommon” in the diplomatic parlance of international multistakeholder initiatives means unrecyclable. The project also took note of the many toxic emissions associated with PVC production.

That’s not surprising since after 30 years of hollow promises and pilot projects doomed to fail, virtually no post-consumer PVC is recycled.3 Conversely, leading brands with forward-looking materials policies such such as Nike, Apple, and Google have prioritized PVC phase outs.4

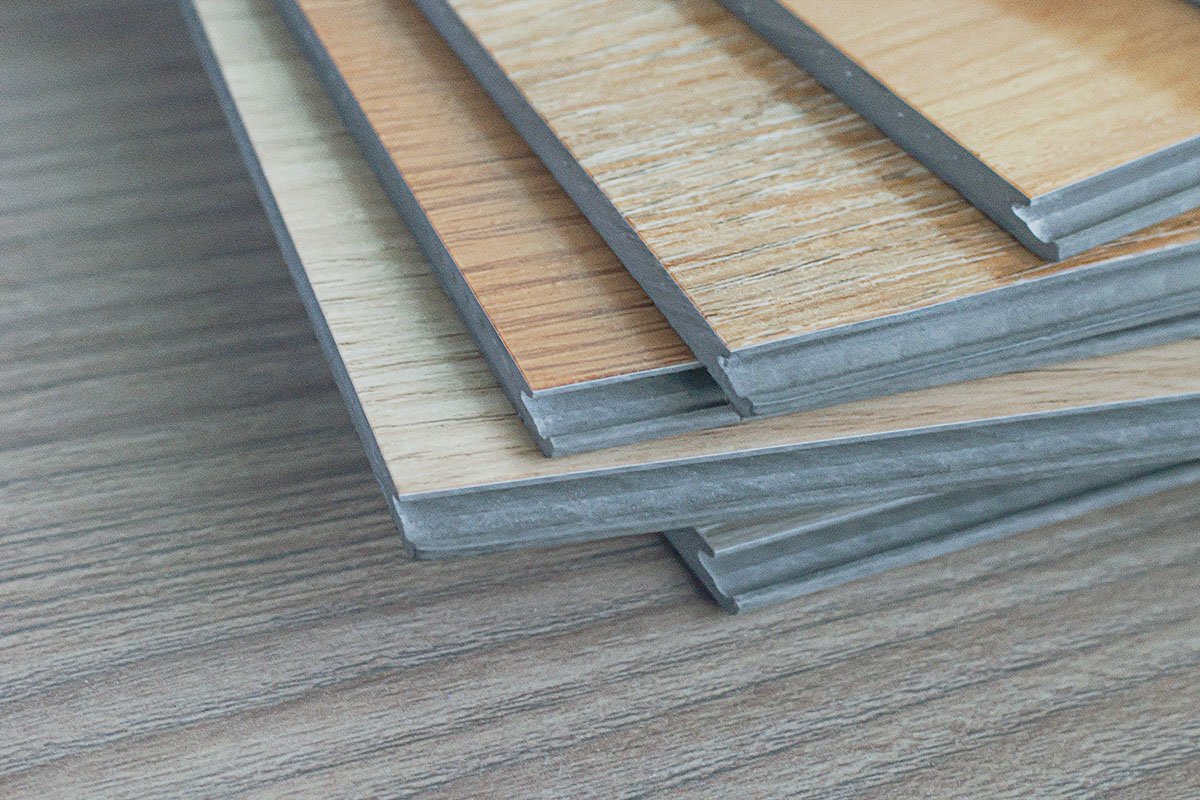

But in the building industry, PVC rages on. Virgin vinyl LVT flooring is the fastest growing product in the flooring sector. So much so that in 2017 sustainability leader Interface introduced a new product line of virgin vinyl LVT, despite forecasting just one year before that by 2020 the company would “source 95 percent of its materials from recycled or biobased resources.”5

The current flooring market demands the impossible – aesthetic qualities and durability at a price unmatchable by non-vinyl floor coverings. A price that is unmatchable because at every stage of vinyl production, the societal costs of its poisonous environmental health consequences are externalized, subsidized, paid for by the people who live in communities that have become virtual poster children for environmental injustice and oppression. Places like Mossville, LA; Freeport, TX; and the Xinjiang Province in China, home to the oppressed Uighur population. As we detail in our exhaustive Chlorine and Building Materials report, the unique chlorine component of PVC plastic contributes to a range of toxic pollution problems starting with the fact that chlorine production relies upon either mercury-, asbestos-, or PFAS-based processes. This is in addition to the onerous environmental health burdens of petrochemical processing that burden all plastics.

It is true that all plastics contribute to environmental injustices. Virtually all plastics are made from fossil fuel feedstocks, and all plastics share abysmally low recovery and cycling rates. Still, independent experts agree that some plastics are worse than others, and PVC is among the worst.6 Additionally, most uses of PVC have readily available alternatives or solutions that are within reach. Certainly there are non-PVC alternatives for flooring. What can’t be beat is the cost – that is, the low purchase price at the point of sale, subsidized by the sacrifices we ignore in the communities where the plastics are manufactured and the waste is dealt with. And BIPOC communities bear the disproportionate burden of it all. Acknowledging and addressing this tradeoff is at the root of the behavioral change that stands between us and a just and healthy circular economy.

In his influential book How To Be An Antiracist, Dr. Ibram X. Kendi argues that if we recognize we live in a society with many racial inequities – and acknowledge that since no racial group is inferior or superior to another, the cause of these inequities are policies and practices – then to be anti-racist is to challenge those policies and practices where we can and create new ones that create equity and justice for all.

Imagine if as part of our commitment to equity in our sustainability efforts, we recognized, acknowledged, and did what we could to address the racial inequities associated with PVC production, and committed right now to stop using PVC unless it was absolutely essential. The plastics industry would howl and point out inconsistencies, question priorities, highlight unintended consequences. We would all feel a tinge of whataboutism – what about carbon, or this other injustice, or that shortcoming of the alternatives. But it is clear that widespread incrementalism is failing us on so many fronts, none more than the environmental injustices that are hardwired into our supply chains.

In fact, there are many examples of companies and building projects that have prioritized PVC-free alternatives based upon principles of equity and justice. We need more leaders in the field to join those who are abandoning vinyl in product types that have superior options. Our CEO Gina Ciganik used a non-PVC flooring in 2015 at The Rose, her last development project prior to joining HBN.

First Community Housing, another affordable housing leader, has been using linoleum for many years for similar reasons. In their Leigh Avenue Apartments project. Forbo’s Marmoleum Click tiles were the flooring of choice.

Vinyl is not an essential material for any of the largest surface areas of our building projects – flooring, wall coverings, or roofing. It may often be the conventional choice in conventional buildings, but it should not be the conventional choice in buildings that promise to be green, healthy, and equitable. LVT may be the fastest growing flooring product in the world, but it is a throwback to the inequitable, unsustainable world we say is unacceptable, not the world we are trying to create.

Habitable can help you start by using our Informed™ product guidance, which helps identify worst and best in class products that are healthier for people and the planet. So why not start here and now, with a principled stand of refusing to profit from unjust, frequently racist, externalized costs?

SOURCES

- https://plasticsrecycling.org/pvc-design-guidance

- See pp. 27-29: www.newplasticseconomy.org/assets/doc/New-Plastics-Economy_Catalysing-Action_13-1-17.pdf

- See e.g. Figure 1: https://css.umich.edu/publication/plastics-us-toward-material-flow-characterization-production-markets-and-end-life

- See e.g.: www.apple.com/environment/answers (Apple); www.greenpeace.org/usa/reports/greener-electronics-2017 (Google); www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-aug-26-fi-16540-story.html (Nike)

- www.greenbiz.com/article/inside-interfaces-bold-new-mission-achieve-climate-take-back: “Going Beyond Zero” The march towards Mission Zero continued unabated, however, with consistent year-over-year improvement in most metrics. Today, the company forecasts that by 2020 it will halve its energy use, power 87 percent of its operations with renewable energy, cut water intake by 90 percent, reduce greenhouse gas emissions 95 percent (and its overall carbon footprint by 80 percent), send nothing to landfills, and source 95 percent of its materials from recycled or biobased resources.

- www.cleanproduction.org/resources/entry/plastics-scorecard-press-release

While attending a 2018 meeting of U.S. EPA’s National Environmental Justice Advisory Council (NEJAC) in Boston, I heard the testimony of Delma and Christine Bennet. They live in Mossville, LA, amidst what is likely the nation’s largest concentration of PVC (polyvinyl chloride) manufacturing facilities. I was there to present the findings of HBN’s inventory of pollution associated with the chlorine/PVC supply chain.

Our study found, among other things, that the Gulf Coast region (which includes Mossville) is home to nine facilities that use outmoded asbestos technology, and home also to some of the industry’s worst polluters: Five of the six largest emitters of dioxins––a long lasting, extremely toxic family of hazardous waste that causes cancer and many other health impacts, are located there. The Bennets reminded the EPA that according to studies by a division of the Centers for Disease Control, Mossville residents have three times higher levels of dioxin in their blood than average Americans, and the dioxin levels found in their yards and attic dust exceed regulatory standards typically used for toxic waste remediations of industrial sites. Even the vegetables in their gardens tested positive for dioxin.

When I think about why we fight so hard to exclude PVC from any palette of green, healthy, or sustainable building materials, I think first of people like Delma and Christine. I then think about the many non-profits, government agencies, and private enterprises dedicated to recycling. Way back in the 1990’s, the industry Association of Plastic Recyclers declared PVC a contaminant to the recycling stream. A generation later, a 2016 study by the Circular Economy evangelist Ellen MacArthur Foundation called out PVC packaging for global phase-out, citing low recycling rates and chemical hazard concerns. Much of the concern about PVC packaging is driven by worries about ocean pollution. HBN’s study found that at least one U.S. PVC manufacturer is routinely dumping tons of PVC pellets into local waterways and refusing to stop even after being ordered to do so by the state of Texas.

The list goes on. Our report documents the types of industrial pollution in addition to dioxin that could be reduced or avoided by a switch to more recyclable plastics that are not made with the chlorine that is an essential ingredient of PVC, including ozone depleting and potent global warming gasses. HBN’s earlier studies have documented the hazards posed by legacy pollutants that are returning to our consumer products in recycled PVC content––heavy metals such as lead, and endocrine-disrupting plasticizers known as phthalates.

There is a better way.

There is virtually no use of PVC in building products that could not be replaced with another plastic or other material. Indeed, from siding, to wallpaper, to window frames, PVC has displaced materials that are more recyclable, such as aluminum and paper. Because the industry is not held accountable for the environmental health damages wrought in places like Mossville, PVC has artificially low costs that present barriers to entry, or inhibit market expansion of less hazardous, more sustainable alternatives.

That is why PVC should not be part of any building, or any building rating system, that claims to advance environmental and health objectives. It’s not green. It’s not healthy. It’s not sustainable. It’s just cheap––for us. Because folks like Delma and Christine Bennet pay the true cost.

Know Better

Learn more about the implications of chlorine as a feedstock in plastics in HBN’s Chlorine and Building Materials report.

Pollution

Pollution