Keep reading about similar topics.

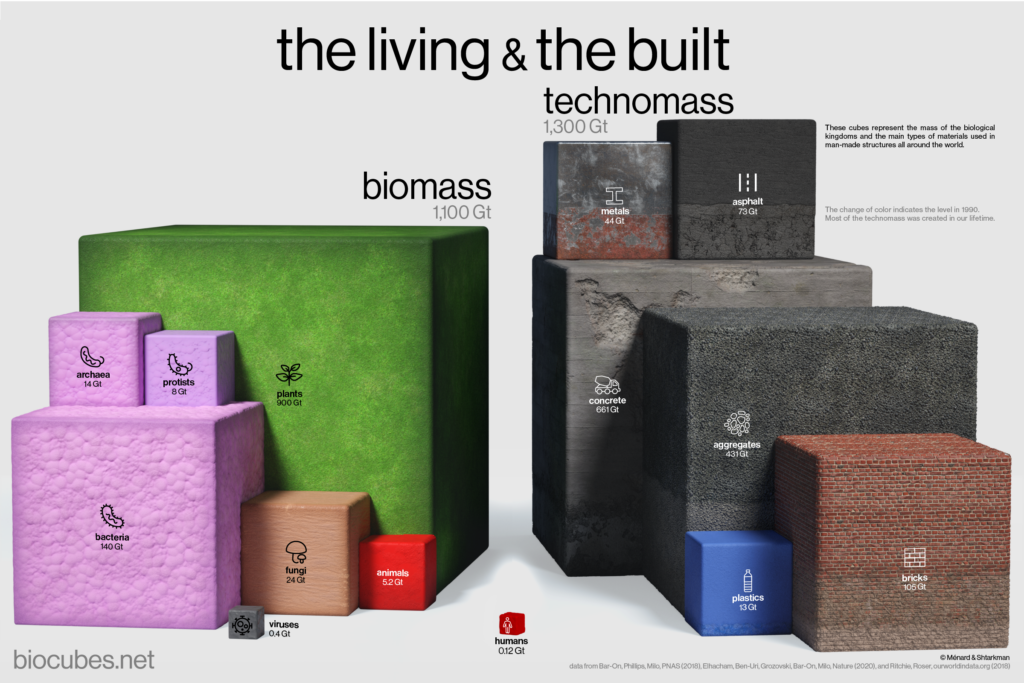

Our global ecological footprint has reached unprecedented levels.2 Humanity’s total material demand–our buildings, roads, machines, and products–now outweighs all living things on Earth.3 These aren’t just statistics, they are a wake-up call for everyone working in sustainability and materials management.

I’ve spent the last two decades working on climate impact and waste assessment for companies and governments across the United States, and have watched as local sustainability efforts have flourished while the global environmental picture becomes more and more grim. One of the biggest challenges I’ve seen is that the traditional metrics of sustainability–carbon footprints, waste reduction targets, efficiency gains–are designed to drive localized, regional progress. These measures of ‘success’ overlook a crucial reality: when we cut costs and resource use in one place, consumption often increases somewhere else in the world. As sustainability professionals leading the charge for a more just and regenerative future, our biggest challenge today is not merely advancing existing measures of ‘success.’ Instead, we must fundamentally reimagine our relationship with an economic system that prioritizes growth above all else and shift toward one that values health through balance and harmony with nature. When the planet is healthy, we are healthy.

This reality is pushing sustainability leaders to ask harder questions: How can we create genuine prosperity while respecting Earth’s ecological limits? What would it look like to build a materials economy that serves both people and planet? The answers require us to examine not just how we manage materials, but how we think about growth itself.

There is already a great body of knowledge on “the ability to thrive as a society, while respecting biophysical limits.”4 This wisdom, however, stems from ways of living and being that do not center economic size as a marker of societal well-being. In contrast, the goal of most economies around the world today is to simply grow.

The Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy recently showed that the world’s seven largest economies have enshrined “economic growth” as a goal in and of itself, detached from any kind of social or well-being metrics.5 But economic growth doesn’t happen in a vacuum: our environment, people, and communities are all impacted by macroeconomic decisions. Considering this, three key issues emerge that challenge our perception of growth’s ‘success’:

We must acknowledge and work within Earth’s limits to economic growth. Our collective ecological demands have been outpacing the regenerative capacity of our planet since the 1970s.10 Globally, we’ll need to shrink the total size of that demand in order to bring our footprint back in balance with nature.

Humans’ fossil-fueled economy has pushed the global climate past its natural limits: recent highly visible weather events related to our changing climate are symptomatic of pushing past ecological constraints. This isn’t unique to climate–all natural systems have boundaries and it is now time for us to work within the boundaries of a healthy, thriving planet.

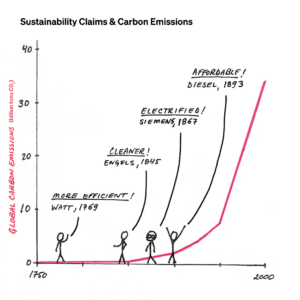

Efficiency gains must be coupled with limits on total ecological demand. To date, the most common approach for reducing ecological demand has been introducing more efficient technologies: new power plants, more fuel-efficient engines, and ever-smaller computing devices deliver their services with less material input per unit of output. But when we reduce resource use through efficiency, a growth-focused economy uses those saved resources to consume more elsewhere. It’s like squeezing a balloon – the air just moves to a different spot.

The factors that drive ecological change on planet earth are connected to commodity flows that operate across political boundaries, meaning reduced demand in one part of the economy is easily offset by increased consumption in another. For example, the U.S. has reduced its fossil fuel demand over the past two decades, but the global economy has easily reallocated those savings in the planetary push for economic growth. In practice, efficiency gains are often redirected into making more products, feeding a cycle of continuous growth that ultimately leads to more extraction, more waste, and more strain on our planet’s systems.

Illustration by John Mulrow, PhD

Sustainability strategies must prioritize equity alongside environmental goals. Our traditional, Western understanding of economic growth prioritizes gain for a small subset of the global population. Even if economic growth were intended to benefit all humanity, it has failed in practice.

In his book Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World, Jason Hickel presents data showing that while global GDP per capita increased fivefold between 1980-2016, this growth was highly unequal, with only the wealthiest 10% of people seeing their incomes grow at or above this rate. The richest 1% gained disproportionately more, while the vast majority of people experienced minimal economic benefits despite overall growth.11 This pattern repeats even within high-income countries, as Matt Orsagh, a post-growth finance advocate, has pointed out. In the US, it is also the wealthiest 10% of people that have accumulated the majority of economic growth for themselves in recent decades.12 Clearly, there is a need to rebalance and redefine economic flows so that when and where growth happens it benefits those truly in need.

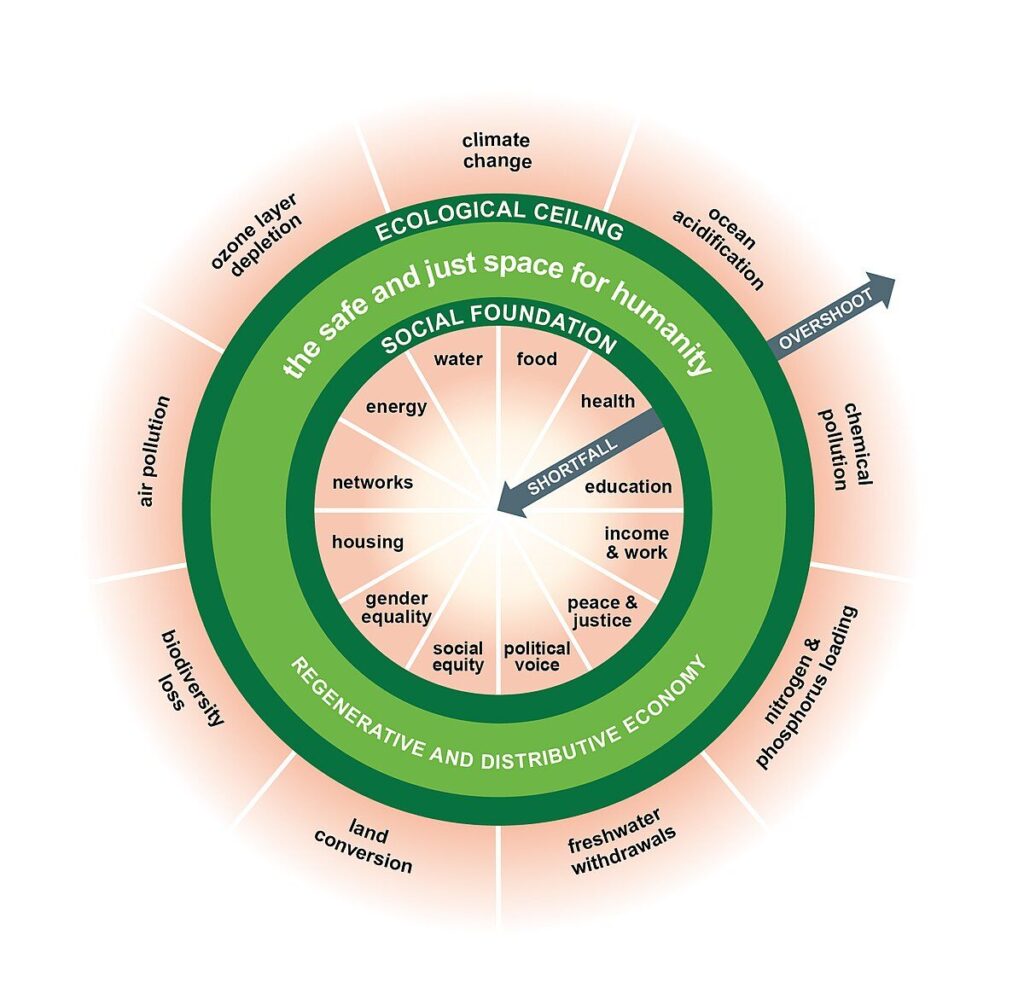

Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics concept has provided a framework for seeking social and environmental sustainability without prioritizing growth for growth’s sake. The doughnut diagram represents a safe and just operating space for humanity, with the inner boundary representing minimum requirements for human well-being (the social foundation), and the outer boundary representing planetary systems impacted by economic activity (ecological ceiling).

The reality is that social foundation metrics are not being met for many across the world and yet we are exceeding planetary boundaries, atmospheric CO2 levels being just one of several ecological emergencies. Raworth’s work has been effective at helping sustainability professionals break from efficiency as a marker of environmental impact reduction, instead pairing planetary-scale impact metrics with socioeconomic ones like equity and access.

New ways of thinking about growth bring fresh focus to the fundamental question of what truly constitutes ‘wealth’ versus ‘well-being.’ While social and ecological metrics provide important global context, numbers alone won’t be enough to persuade a critical mass of environmental advocates and professionals to break from the commitment to growth embedded in most sustainability plans.

To orient away from growth, we’ll need enticing ways to live the good life with less economic throughput. That’s why this reimagining of economics prompts psychological inquiries into the question “how much is enough?”, explorations of indigenous ways of knowing and being, and long-standing critiques of economic development goals aimed at increasing Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as the sole marker of societal well-being.

As a sustainability professional on this journey, I constantly remind myself that the path beyond growth is still being trodden. It extends from many places in humanity’s past, and the justifications for redefining growth are not solely technical; ongoing ecological degradation is not in need of ever-more refined climate, energy, and economic forecasting techniques. Economic growth is a social and political commitment embedded in daily life. Challenging it necessitates action in both personal and professional spheres.

Here are some steps to begin:

For those based in the U.S., various organizations—including the Post Growth Institute, CASSE, Arketa Institute, and DegrowNYC—are advancing the movement through discussion, debate, and action.

Remember, the goal isn’t perfection—it’s progress toward a materials economy that works for both people and planet. Each step we take builds momentum for broader change. The transition to balance our ecological footprint won’t be easy, but it’s essential for a shared future. As sustainability professionals, we have the opportunity–and responsibility–to lead this transformation. By taking these concrete steps within our organizations, we can help create a future where innovation serves the goal of true sustainability rather than limitless growth.

John Mulrow, PhD

John Mulrow is Executive Director of the Degrowth Institute and Adjunct Assistant Professor of Environmental and Ecological Engineering at Purdue University. His work is focused on improving environmental assessment methodology through perspectives that prioritize social equity and limits to growth. He holds a PhD in Civil Engineering from University of Illinois Chicago and a BS in Earth Systems from Stanford University.

Ecological footprint: Economic goods and services require inputs that originate from natural systems

Ecological resources include raw materials such as water, fuels, plants, and mineral ores and natural functions such as water flow, photosynthesis, and atmospheric circulation.

Ecological demand is the ecological footprint required to meet human wants and needs.

Ecological constraints are the limits of demand, beyond which certain natural systems become destabilized. These limits can be characterized in many ways but we prefer the Stockholm Resilience Institute’s planetary boundaries framework.