READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

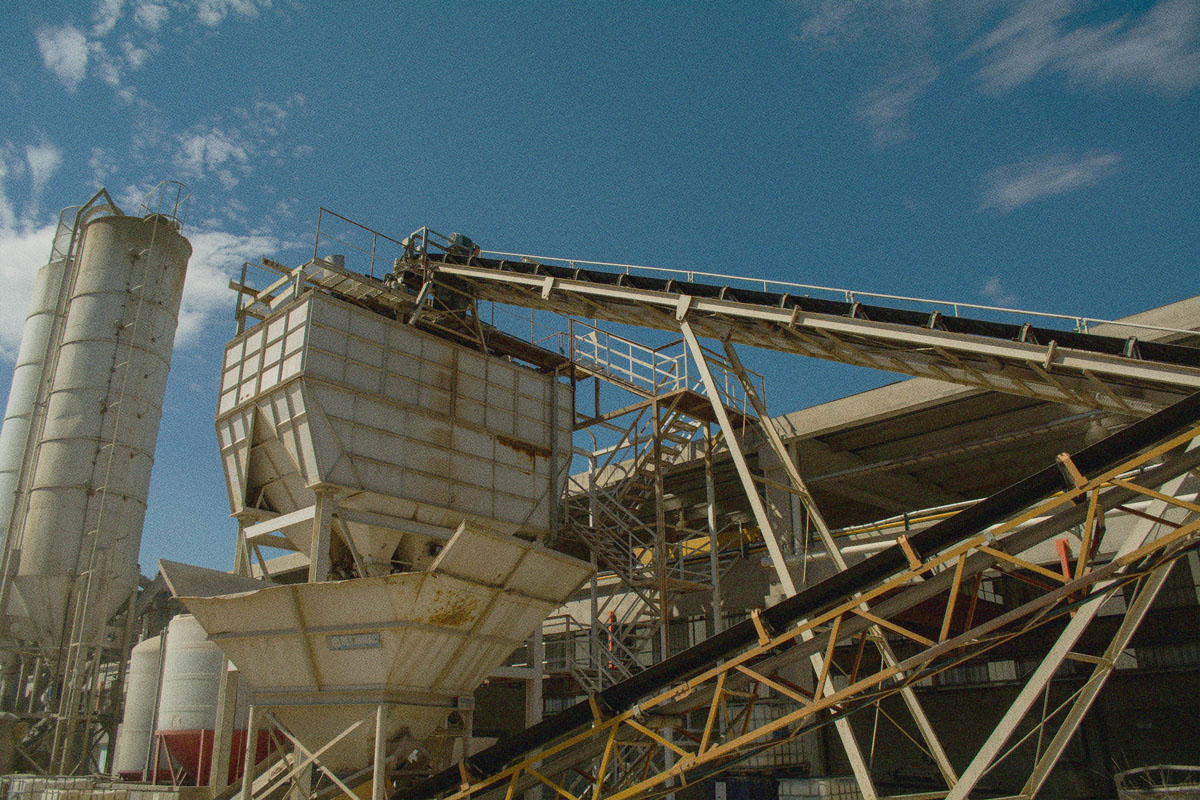

In this case study, Healthy Building Network and Energy Efficiency for All teamed up to apply a framework for considering life cycle chemical and environmental justice impacts to the primary component of spray polyurethane foam insulation: isocyanates.

The case study explores the chemical hazards associated with the manufacture of isocyanates and the localized impacts that facilities have on communities and workers. It includes an example of chemical movements within the supply chain and highlights end of life scenarios for SPF. Overall findings are coupled with specific recommendations for policymakers and for manufacturers throughout the supply chain.

Supporting Documents:

Product manufacturers, policymakers, and professionals in the building industry are paying more attention to the potential health and environmental impacts of building products during installation and use, but there has been less consideration of the important chemical impacts, including contributions to environmental injustice or environmental racism, that may occur during other life cycle stages.

Healthy Building Network (HBN) teamed up with Energy Efficiency for All (EEFA) to expand understanding of products’ life cycle health and environmental justice impacts. Together, the two organizations developed a framework based on the principles of green chemistry and the principles of environmental justice, and applied this framework to two widely-used insulation materials: fiberglass and spray polyurethane foam (SPF) insulation.

Supporting Documents:

- Case study on Isocyanates in Spray Polyurethane Foam

- Case study on Glass Fibers in Fiberglass Insulation

This chapter in ILFI’s book The Regenerative Materials Economy explores the often overlooked life cycle chemical and environmental justice impacts of building materials, focusing on insulation materials like fiberglass and spray polyurethane foam (SPF).

Through a framework rooted in green chemistry and environmental justice principles, authors Rebecca Stamm of HBN and Veena Singla of NRDC analyze manufacturing realities, environmental justice concerns, and environmental health impacts, providing recommendations to improve the industry’s sustainability and reduce the negative effects on marginalized communities.

What do building materials have to do with social justice? Learn more in this article by Diana Alley, Avideh Haghighi, and Lona Rerickat at ZGF Architects.

The Louisville Charter for Safer Chemicals, endorsed by over 100 organizations, confronts the chemical industry’s role in the climate crisis and provides guidance for advancing environmental justice in communities disproportionately affected by harmful chemical exposure.

Healthy Building Network (HBN) and 100+ organizations stand united behind the new Louisville Charter for Safer Chemicals, a roadmap for transforming the chemical industry to one that is no longer a source of greenhouse gas emissions and significant human and environmental health harms.

The goal of the updated charter is to protect human health and the environment and achieve environmental justice for all who experience disproportionate impacts from cumulative chemical sources, including people of color, low-income people, Tribes and Native/Indigenous communities, women, children, and farmworkers.

The original Charter was created in 2004; at that time, HBN joined a broad coalition of grassroots, labor, health, and environmental justice groups in an extensive process initiated by community organizations in Louisville, KY. Louisville’s “Rubbertown” area hosted 11 industrial facilities that released millions of pounds of toxic air emissions every year. The Charter was named in honor of this city and all of the communities across the nation exposed to toxic chemical contamination—starting with the people who are harmed first and worst. We participated in the 2021 update process, supporting the efforts of the most heavily impacted communities to more explicitly address the chemical industry’s massive contribution to the climate crisis, and the need to advance environmental justice in communities who are disproportionately impacted.

The Louisville Charter is a unifying guide for everyone working to ensure that toxic chemicals are no longer a source of harm, from local and national policy-makers and labor organizers, to health care workers and concerned community members, to committed leaders in the building industry. It is meant to be versatile and used in a wide variety of contexts for one overarching purpose: to overhaul chemical policies in favor of safety, health, equity, and justice, and avoid false solutions that simply shift harms to other people and places.

HBN is proud to be a signatory of the Charter and join this diverse and intersectional community of partners demanding urgent action to protect, strengthen, and restore our most vulnerable communities.

To learn more about the Louisville Charter for Safer Chemicals and its ten platform planks, visit www.louisvillecharter.org.

“When I came here, my unit was on the brink of falling apart. We had so many problems; the carpets were incredibly old, and turning the AC on was like having a helicopter inside the house.”

These are the words of Vanessa del Campo. She was born and raised in Mexico and like many other people, she moved to the United States searching for safer and better living conditions. She now lives in Minnesota and rents a small unit in a multifamily apartment building located in one of the areas designated by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) as of Environmental Justice concern. Her experience as a tenant is filled with stories of unjust evictions, health concerns, and constant battles with unlawful landlords that neglected her right to even the most basic human living conditions.

Fortunately for Vanessa and other neighbors in her building, she received support from a community-based organization, Renters United for Justice (abbreviated IX from its name in Spanish), that helped them organize and mobilize to reclaim desperately needed services to maintain their health and wellbeing. What began as an organized effort to request new windows for a handful of apartment units turned into an exhausting but successful journey to purchase the run-down complex of apartment buildings from their landlord and secure a loan to renovate all the apartments.

It’s easy to get lost in Vanessa’s excitement as she talks about this newfound opportunity. She mentioned that her baby had a tough time learning to crawl because it was too dangerous to place her on the ground due to rats and cockroaches often running past her. At the same time, it is also easy to forget that in addition to being a mother and having a demanding job, she now has to fulfill the role of a building co-owner as a leading member of the newly formed residents’ collective (A Sky Without Limits).

With so much work going into buying and renovating the apartment complex, the residents had little time to think about the chemical safety of their chosen building materials. That’s where HBN came in. In 2021 the MPCA awarded IX and Healthy Building Network a grant to work together to reduce toxic chemical exposures among children, pregnant individuals, employees, and communities who are disproportionately impacted by harmful chemicals used in common products.

One example of toxic chemicals in homes are phthalates, or orthophthalates, which are chemicals that help make plastics flexible. They can also impact the proper development of children. These chemicals are banned in children’s toys in the U.S., and The Minnesota Department of Health in partnership with MPCA named phthalates as “Priority Chemicals” as part of the 2017 Toxic-Free Kids Act. While many manufacturers have phased out hazardous phthalate plasticizers, existing vinyl flooring, especially those installed 2015 and earlier, likely contain these potential developmental toxicants. This translates to dozens of pounds of these hazardous chemicals in the floor of a single apartment unit. As these chemicals are released from products, they deposit in dust, which can be inhaled or ingested by residents – particularly young children who are crawling on floors and often place their hands in their mouths.

“Honestly, we never stopped to think about how harmful [building] materials could be.” Vanessa said. “It was just regrettable to see how we were living. We understand that the new materials that are going into our buildings today may not be the healthiest. Today, we realize it is important to think about how we want to live in our homes, to imagine the quality of life we want in our buildings, in our community.”

Over the coming year, HBN will work with IX and the residents’ collective to evaluate the materials used in their ongoing renovation process and provide recommendations to improve material selection. We will also develop resources tailored to residents to enhance their understanding of how the surrounding environment influences their health. To extend the impact of this work, we will create and share a set of best practices that property managers and tenant organizations can use to advocate for healthier materials in the communities they live in and properties they manage.

“Our collaboration with HBN is timely. By working together with the property managers, we can raise their awareness about how their work impacts our health and help change how they select materials,” Vanessa said.

At Healthy Building Network, we are grateful for the opportunity to work with IX and local leaders like Vanessa through the MPCA grant that makes this collaboration possible. We call on public agencies, foundations, and private investors to fund initiatives that seek to dismantle health inequities through direct investment in the communities disproportionately impacted by environmental injustice, especially related to toxic chemical exposures. We look forward to sharing with you the lessons, stories, and resources that come out of this collaboration.

To learn more about selecting healthier products, visit our Informed™ website, which includes a wide range of resources and tools to help you find healthier material options.

Un inquilino clama por viviendas más seguras y saludables

“Cuando llegué aquí, mi apartamento estaba a punto de desmoronarse. Tuvimos muchos problemas; las alfombras eran increíblemente viejas y encender el aire acondicionado era como tener un helicóptero dentro de la casa”. Estas son las palabras de Vanessa del Campo.

Vanessa nació y creció en México, y como muchas otras personas, se mudó a los Estados Unidos en busca de mejores condiciones de vida. Ahora vive en Minnesota y alquila un apartamento en un edificio multifamiliar ubicado en una de las áreas designadas por la Agencia de Control de Contaminación de Minnesota (MPCA) como de interés de Justicia Ambiental. Su experiencia como inquilina está marcada con historias de desalojos injustos, preocupaciones de salud, y batallas constantes con propietarios que negaron su derecho a incluso las condiciones más básicas de vida.

Afortunadamente para Vanessa y otros vecinos en su edificio, ella recibió el apoyo de Inquilinos Unidos por Justicia (IX), una organización comunitaria que les ayudó a organizarse y movilizarse para recuperar los servicios que desesperadamente necesitaban para mantener su salud y bienestar. Lo que comenzó como un esfuerzo organizado para solicitar nuevas ventanas para un pequeño número de apartamentos, se convirtió en una larga pero exitosa tarea para comprar el destartalado complejo de apartamentos y asegurar un préstamo para renovar todas sus unidades.

“Pasamos por muchos litigios con el propietario porque no estaba haciendo las reparaciones que necesitábamos y no quería vendernos los edificios. El año pasado, cuando llegó la pandemia, finalmente obtuvimos la oportunidad de comprar el edificio. Fue un momento feliz y difícil porque estábamos aterrorizados de enfermarnos [con el virus], pero logramos organizarnos y apoyarnos unos a otros. Hoy estamos trabajando con una nueva empresa de administración de propiedades y el banco para instalar alfombras, pisos, techos, ventanas, hornos, refrigeradores y baños nuevos. Estamos haciendo una profunda renovación para llevar todos los apartamentos a un estado que es mucho, mucho mejor que el que teníamos”.

Es fácil dejarse llevar por la emoción de Vanessa mientras habla de esta nueva oportunidad. Ella mencionó que su bebé tuvo dificultades para aprender a gatear porque era demasiado peligroso colocarle en el suelo debido a las ratas y cucarachas que a menudo rondaban la casa. Al mismo tiempo, también es fácil olvidar que además de ser madre y tener un trabajo exigente, ahora tiene que cumplir el rol de copropietaria de un edificio como miembro principal de un recién formado colectivo de residentes (Un Cielo Sin Límites).

Con tanto trabajo invertido en la compra y renovación del complejo de apartamentos, los residentes tuvieron poco tiempo para pensar en la seguridad química de los materiales de construcción que fueron utilizados en sus apartamentos. Ahí es donde entra Healthy Building Network (HBN, o, La Red de Edificios Saludables). A principios de este año, MPCA otorgó a IX y HBN una subvención para reducir la exposición a sustancias químicas tóxicas entre los niños, las personas embarazadas, los empleados y las comunidades que se ven afectadas de manera desproporcionada por sustancias químicas nocivas utilizadas en productos comunes.

Un ejemplo de sustancias químicas tóxicas en los hogares son los ftalatos u ortoftalatos, que son sustancias químicas utilizadas para ayudar a dar flexibilizar a los plásticos. Estas sustancias también pueden afectar el desarrollo adecuado de los niños. Estos productos químicos están prohibidos en los juguetes de los niños en los EE. UU. El Departamento de Salud de Minnesota, en asociación con MPCA, nombró a los ftalatos como “productos químicos prioritarios” como parte de la Ley de Niños Libres de Tóxicos de 2017. Si bien muchos fabricantes han eliminado los plastificantes de ftalato, estos químicos están presentes en los pisos de vinilo existentes, especialmente los instalados antes de 2016. Esto se traduce en docenas de libras de estos químicos peligrosos en el piso de una sola unidad de apartamento. A medida que estos productos químicos se liberan de los productos, se depositan en el polvo que los residentes pueden inhalar o ingerir, afectando especialmente a los niños pequeños que gatean por el suelo y a menudo se llevan las manos a la boca.

“Honestamente, nunca nos detuvimos a pensar en lo dañino que podrían ser los materiales [de construcción]”. Dijo Vanessa. “Fue lamentable ver cómo vivíamos. Entendemos que los materiales que se utilizan en nuestros edificios hoy en día pueden no ser los más saludables. Hoy nos damos cuenta de que es importante pensar en cómo queremos vivir en nuestros hogares, imaginar la calidad de vida que queremos en nuestros edificios, en nuestra comunidad”.

Durante el próximo año, HBN trabajará con IX y el colectivo de residentes para evaluar los materiales utilizados en su proceso de renovación y brindar recomendaciones para mejorar la selección de materiales. También desarrollaremos recursos para ayudar a los residentes a entender cómo el entorno circundante influye en su salud. Para extender el impacto de este trabajo, crearemos y compartiremos un conjunto de mejores prácticas para que los administradores de propiedades y las organizaciones de inquilinos puedan abogar por utilizar materiales más saludables en las comunidades en las que viven y en las propiedades que administran.

“Nuestra colaboración con HBN es oportuna. Al trabajar junto con los administradores de propiedades, podemos aumentar su conciencia sobre cómo su trabajo impacta nuestra salud y ayudar a cambiar la forma en que seleccionan los materiales”, dijo Vanessa.

En Healthy Building Network, estamos agradecidos por la oportunidad de trabajar con IX y líderes locales como Vanessa a través de la subvención otorgada por MPCA que hace posible esta colaboración. Hacemos un llamado a las agencias públicas, fundaciones e inversionistas privados para que financien iniciativas que busquen desmantelar las inequidades en salud a través de inversión en las comunidades impactadas de manera desproporcionada por la injusticia ambiental, especialmente relacionada con la exposición a sustancias químicas tóxicas. Esperamos pronto poder compartir con ustedes las lecciones, historias y recursos que surgen de esta colaboración.

In this article, we aim to expand your thinking about the cost of materials to account for the costs borne by individuals and fenceline communities who are exposed to toxic chemicals every day. The bottom line is that some products can be sold cheaply because someone else is carrying the burden of the true cost.

Where We Are

When you shop for a flooring product, what do you consider? Perhaps you think about the look and feel of the product and its durability. You likely also consider the price. The cost of using a material is influenced by the cost to purchase the product itself, the installation cost, maintenance costs, as well as how long the product will last (when you will have to pay to replace it). These are all internalized costs, paid by the building owner.

These costs alone, however, do not consider the full impacts of materials along their life cycles. More and more building industry professionals are paying attention to the content of building products and working to avoid hazardous chemicals in an effort to help protect building occupants and installers from health impacts following chemical exposures. To understand the true, full cost of a product, we must look beyond just the monetary cost of purchasing and maintaining a product.

Hidden Costs

Many of the costs associated with products are more or less hidden when choosing a building material. Just a few of these hidden costs are outlined below.

- Toxic Chemical Impacts on Human Health: This includes direct medical expenses due to diseases caused or exacerbated by chemical exposures, as well as indirect health-related costs like loss of productivity in work or school and decreased economic productivity in terms of loss of years of life and loss of IQ points. It also includes the immeasurable costs to quality of life and loss of loved ones.

- Environmental Contamination Costs: Contamination of the environment with toxic chemicals contributes to the human health impacts noted above. In addition, the costs of environmental contamination can include reduced property values in and around contaminated areas, loss of income and food production from the contamination of farms, and the cost of clean up activities (e.g. utilities clean up of water contamination). Less quantifiable costs include damage to wildlife and ecosystems.

- Climate Change Impacts: Production of chemicals and products is often energy-intensive and based on fossil fuels. Most products contribute to climate change to some extent. Some contribute more than others because of energy use or the release of chemicals with high global warming potential. These greenhouse gas emissions exacerbate climate change, leading to increasingly powerful storms and fires, with increasingly high and recurring costs for recovery. Climate change also magnifies the impacts of toxic chemicals, increasing the human and environmental health costs.

- Environmental Injustice: Disproportionately, the health impacts and associated costs throughout the life cycle of products (e.g. during manufacturing and at end of life) fall on communities of color and low-income communities. The numerical cost of these impacts may not be quantifiable, but the costs to our society are no less clear as a result.

Some Numbers

Quantifying the estimated costs of these impacts is challenging. In most cases, there is just not enough data to estimate the full costs of hazardous chemical impacts. Below are examples of estimated direct and indirect costs of some toxic chemicals to society.

Toxic Chemical Impacts on Human Health

The US Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA) estimates that American workers alone suffer more than 190,000 illnesses and 50,000 deaths per year that are related to chemical exposures. These chemical exposures are tied to cancers, as well as other lung, kidney, heart, stomach, brain, and reproductive diseases.1

While some workers may see greater exposures to hazardous chemicals, all of us are impacted. Many of you are likely familiar with PFAS, aka per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. PFAS have been used in a wide range of applications, including stain-repellent treatments for carpet and countertop sealers. The widespread use of PFAS has led to extensive contamination of the planet and people. Increasing research and attention to this group of chemicals has led to some quantitative understanding of the costs to society of their use. A recent publication in Environmental Science and Technology outlined some of the true costs of PFAS chemicals. The authors highlight that, “A recent analysis of impacts from PFAS exposure in Europe identified annual direct healthcare expenditures at €52–84 billion. Equivalent health-related costs for the United States, accounting for population size and exchange rate differences, would be $37–59 billion annually.” Importantly, they further call out the fact that, “These costs are not paid by the polluter; they are borne by ordinary people, health care providers, and taxpayers.”2

And this is just the cost of one group of chemicals. Another recent study estimated the cost of US exposures to phthalates, a group of chemicals used to make plastics more flexible, to be approximately $40 billion or more due to loss of economic activity from premature deaths.3 While more research is needed, the scale of these estimated costs is staggering.

Environmental Contamination Costs

The release of PFAS chemicals has contaminated water supplies globally. About two-thirds of the US population receives municipal drinking water that is contaminated with PFAS. Reducing the levels of PFAS in drinking water can be expensive, and none of the methods fully remove PFAS. In the Environmental Science and Technology study mentioned above, the authors note that “following extensive contamination by a PFAS manufacturer in the Cape Fear River watershed, Brunswick County, North Carolina is spending $167.3 million on a reverse osmosis plant and the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority spent $46 million on granular activated carbon filters, with recurring annual costs of $2.9 million. Orange County, California estimates that the infrastructure needed to lower the levels of PFAS in its drinking water to the state’s recommended levels will cost at least $1 billion.” Again, these costs are typically not paid by the polluter but shifted to the public.4

Climate Change Impacts

Chemicals used in the production of some PFAS are ozone depleters and potent greenhouse gases. New research released in September by Toxic-Free Future, Safer Chemicals Healthy Families, and Mind the Store ties the release of one such chemical, HCFC-22, to the production of PFAS used in food packaging. The reported releases of this one chemical from a single facility is equivalent to “emissions from driving 125,000 passenger cars for a year.”5

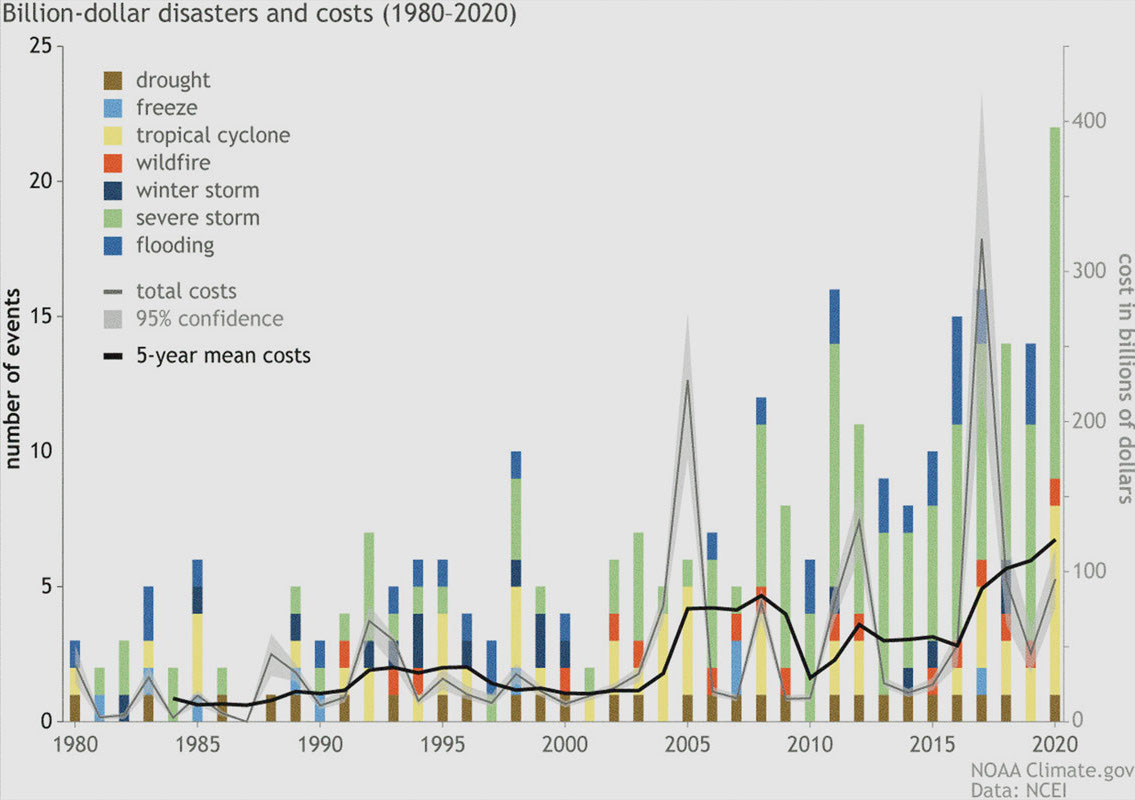

The costs of climate change impacts are immense. For example, the number of billion-dollar disasters and the total cost of damages due to natural disasters have been skyrocketing. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration describes how climate change contributes to increasing frequency of some extreme weather events with billion-dollar impacts. They outline the broader context of these extreme weather events saying that, “the total cost of U.S. billion-dollar disasters over the last 5 years (2016-2020) exceeds $600 billion, with a 5-year annual cost average of $121.3 billion, both of which are new records. The U.S. billion-dollar disaster damage costs over the last 10-years (2011-2020) were also historically large: at least $890 billion from 135 separate billion-dollar events. Moreover, the losses over the most recent 15 years (2006-2020) are $1.036 trillion in damages from 173 separate billion-dollar disaster events.”6

Figure 1. Billion-dollar Disasters and Costs (1980-2020)7

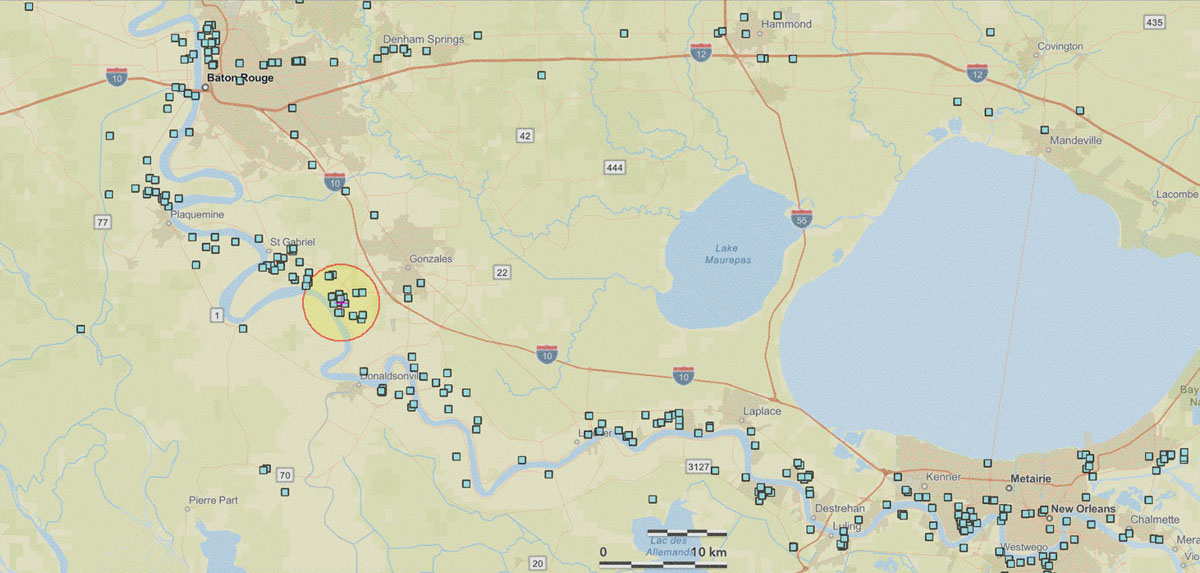

Environmental Injustice

In the US, communities of color and low-income communities are disproportionately impacted by environmental pollutants.8 These communities often face hazardous releases from multiple sources due to high concentrations of manufacturing facilities near their homes. The area along the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge is known as “Cancer Alley” because of the concentration of industrial activity and the associated elevated cancer risks.9 Figure 2 maps facilities that report to EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) in this area. These are facilities that release or manage hazardous chemicals that require reporting to EPA.

The city of Geismar, LA is home to 18 TRI facilities. These facilities reported a total of over 15 million pounds of on-site releases of hazardous chemicals to air, water, and land in 2019.10 Several of these facilities produce chemicals used in the building product supply chain. Two facilities produce chlorine for internal or external production of PVC, which can be used to make pipes, siding, windows, flooring, and other building products.11 Two other facilities manufacture a key ingredient of spray foam insulation, MDI. Some of these facilities have a history of noncompliance with EPA regulations, one having significant violations for eight of the last twelve quarters and another having significant violations for all twelve of the last twelve quarters.12 Surrounding communities are impacted by regular toxic releases from these facilities and are vulnerable to accidents involving toxic chemicals. For example, an explosion and fire at the vinyl plant in 2012 released thousands of pounds of toxic chemicals, led to a community shelter in place order, and shut down roads and a section of the Mississippi River.13

More than 5,000 people live within three miles of one or more of these four facilities. This community is disproportionately Black — 35% of the population compared to 12% in the US overall. Thirty percent of the population is children, with about 1500 kids under the age of 18. This community has a higher estimated risk of cancer from toxics in the air than most places in the US — almost four times the national average.14

Where we go from here?

The message we hope you take away from this article is that we must move beyond discussions based purely on the material costs or up-front costs of products. We must all work together to acknowledge and shed light on the true costs that toxic chemicals have within our society and on specific communities. The impacts of hazardous chemicals are, of course, not just monetary –people’s lives are significantly impacted in multiple ways. The current system subsidizes cheap products by robbing individuals of the opportunity for healthy lives and for children to play, and grow up, and enjoy a full and normal life.

Unfortunately, there is not currently enough information available to make detailed cost accounting broadly possible, and no framework exists for accounting for and comparing the full extent of product costs. Transparency about what is in a product, how the product is made, and hazardous emissions – beyond those required to be reported by law – is critical. Programs that place extended responsibility on manufacturers to manage materials at their end of life (as part of extended producer responsibility or EPR)15 can be a starting point for conversations about the full life cycle impacts of products and can help hold manufacturers accountable for a broader array of costs, once they are better understood.

In the meantime, Habitable works to incorporate a life cycle chemical perspective into our safer material recommendations like our Informed™ product guidance and Pharos database. These tools are a work in progress initially focused on avoiding hazardous chemicals in a product’s content. As a starting point, this helps protect not only building occupants and installers, but also others impacted by those hazardous chemicals throughout the supply chain. When hazardous chemicals are used, it is likely that someone throughout the supply chain is impacted. Informed™ can help you choose safer building products based on the information that we have today as we work to expand our incorporation of life cycle chemical impacts into our research and to provide guidance on a broader range of materials.

Habitable looks forward to continuing to identify and provide the critical data needed to assist in decision making with a more comprehensive view of the true costs of materials, and to developing resources to help communicate the collective return on investment seen by a society where all people and the planet thrive.

SOURCES

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. “Transitioning to Safer Chemicals: A Toolkit for Employers and Workers.” Accessed October 21, 2021. https://www.osha.gov/safer-chemicals.

- Cordner, Alissa, Gretta Goldenman, Linda S. Birnbaum, Phil Brown, Mark F. Miller, Rosie Mueller, Sharyle Patton, Derrick H. Salvatore, and Leonardo Trasande. “The True Cost of PFAS and the Benefits of Acting Now.” Environmental Science & Technology 55, no. 14 (July 20, 2021): 9630–33. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c03565.The original study’s authors note that because data is only available for a few health endpoints and that these costs are likely a minimum health-related cost. See: Goldenman, Gretta, Meena Fernandes, Michael Holland, Tugce Tugran, Amanda Nordin, Cindy Schoumacher, and Alicia McNeill. “The Cost of Inaction : A Socioeconomic Analysis of Environmental and Health Impacts Linked to Exposure to PFAS.” Nordisk Ministerråd, 2019. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:norden:org:diva-5514.

- Trasande, Leonardo, Buyun Liu, and Wei Bao. “Phthalates and Attributable Mortality: A Population-Based Longitudinal Cohort Study and Cost Analysis.” Environmental Pollution, October 12, 2021, 118021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118021.; Guzman, Joseph. “Shocking Study Says Chemicals Found in Shampoo, Makeup May Kill 100k Americans Prematurely Each Year.” The Hill, October 12, 2021. https://thehill.com/changing-america/well-being/576436-shocking-study-says-chemicals-found-in-shampoo-and-makeup-may.

- Cordner, Alissa, Gretta Goldenman, Linda S. Birnbaum, Phil Brown, Mark F. Miller, Rosie Mueller, Sharyle Patton, Derrick H. Salvatore, and Leonardo Trasande. “Correction to The True Cost of PFAS and the Benefits of Acting Now.” Environmental Science & Technology 55, no. 18 (September 21, 2021): 12739–12739. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c04938.

- Schreder, Erika, and Beth Kemler. “Path of Toxic Pollution.” Toxic-Free Future, Safer Chemicals Healthy Families, and Mind the Store, September 2021. https://toxicfreefuture.org/daikin-path-of-toxic-pollution.

- Smith, Adam B. “2020 U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters in Historical Context.” NOAA Climate.gov, January 8, 2021. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2020-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters-historical.

- Smith, Adam B. “2020 U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters in Historical Context.” NOAA Climate.gov, January 8, 2021. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2020-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters-historical.

- Bell Michelle L. and Ebisu Keita, “Environmental Inequality in Exposures to Airborne Particulate Matter Components in the United States,” Environmental Health Perspectives 120, no. 12 (December 1, 2012): 1699–1704, https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1205201; Michael Gochfeld and Joanna Burger, “Disproportionate Exposures in Environmental Justice and Other Populations: The Importance of Outliers,” American Journal of Public Health 101, no. Suppl 1 (December 2011): S53–63, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300121; “Volume 1: Workgroup Report to Administrator,” Environmental Equality: Reducing Risk for All Communities (United States Environmental Protection Agency, June 1992), https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-02/documents/reducing_risk_com_vol1.pdf.

- Tristan Baurick, Lylla Younes, and Joan Meiners, “Welcome to ‘Cancer Alley,’ Where Toxic Air Is About to Get Worse,” ProPublica, October 30, 2019, https://www.propublica.org/article/welcome-to-cancer-alley-where-toxic-air-is-about-to-get-worse; James Pasley, “Inside Louisiana’s Horrifying ‘Cancer Alley,’ an 85-Mile Stretch of Pollution and Environmental Racism That’s Now Dealing with Some of the Highest Coronavirus Death Rates in the Country,” Business Insider, April 9, 2020, https://www.businessinsider.com/louisiana-cancer-alley-photos-oil-refineries-chemicals-pollution-2019-11.

- Data collected from US EPA’s TRI database by searching by city: https://www.epa.gov/toxics-release-inventory-tri-program.

- Vallette, Jim. “Chlorine and Building Materials: A Global Inventory of Production Technologies, Markets, and Pollution – Phase 1: Africa, The Americas, and Europe.” Healthy Building Network, July 2018. https://habitablefuture.org/resources/chlorine-building-materials-project-phase-1-africa-the-americas-and-europe/.

- ECHO. “Detailed Facility Report: BASF Corp.” Data & Tools. Accessed October 21, 2021. https://echo.epa.gov/detailed-facility-report?fid=110000597364.; ECHO. “Detailed Facility Report: Occidental Chemical Corporation.” Data & Tools. Accessed October 21, 2021. https://echo.epa.gov/detailed-facility-report?fid=110000449774.; ECHO. “Detailed Facility Report: Rubicon LLC.” Data & Tools. Accessed October 21, 2021. https://echo.epa.gov/detailed-facility-report?fid=110000597373.; ECHO. “Detailed Facility Report: Westlake Vinyls Co.” Data & Tools. Accessed October 21, 2021. https://echo.epa.gov/detailed-facility-report?fid=110000746328.

- Schade, Mike. “(Yet) Another PVC Plant Explosion and Fire.” Center for Health, Environment & Justice (CHEJ), 2012. http://chej.org/2012/04/16/yet-another-pvc-plant-explosion-and-fire.

- Data is from US EPA’s EJScreen: https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper. Population and demographic information is based on a 3-mile radius around the four facilities combined – Rubicon, Occidental Chemical, BASF, and Westlake Vinyls (location based on latitude and longitude per the Toxic Release Inventory). NATA Air Toxics Cancer Risk is in the 95-100th percentile for the United States.

- OECD defines Extended Producer Responsibility as “a concept where manufacturers and importers of products should bear a significant degree of responsibility for the environmental impacts of their products throughout the product life-cycle, including upstream impacts inherent in the selection of materials for the products, impacts from manufacturers’ production process itself, and downstream impacts from the use and disposal of the products.” See: OECD. “Fact Sheet: Extended Producer Responsibility.” Accessed October 21, 2021. https://www.oecd.org/env/waste/factsheetextendedproducerresponsibility.htm.

Plastic is a ubiquitous part of our everyday lives, and its global production is expected to more than triple between now and 2050. According to industry projections, we will create more plastics in the next 25 years than have been produced in the history of the world so far.

The building and construction industry is the second largest use sector for plastics after packaging.1 From water infrastructure to roofing membranes, carpet tiles to resilient flooring, and insulation to interior paints, plastics are ubiquitous in the built environment.

These plastic materials are made from oil and gas. And, due to energy efficiency improvements, for example–in building operations and transportation–the production and use of plastics is predicted to soon be the largest driver of world oil demand.2

Plastic building products are often marketed in ways that give the illusion of progress toward an ill-defined future state of plastics sustainability. For the past 20 years, much of that marketing has focused on recycling. But for a variety of reasons, these programs have failed.

A recent study from the University of Michigan makes it clear that the scale of post-consumer plastics recycling in the US is dismal.3 Only about 8% of plastic is recycled, and virtually all of that is beverage containers. Further, most of the recyclate is downcycled into products of lower quality and value that themselves are not recyclable. For plastic building materials, the numbers are more dismal still. For example, carpet, which claims to have one of the more advanced recycling programs, is recycled at only a 5% rate, and only 0.45% of discarded carpet is recycled into new carpet. The rest is downcycled into other materials, which means their next go-around these materials are destined to be landfilled or burned.4 After 20 years of recycling hype, post-consumer recycling of plastic building materials into products of greater or equal value is essentially non-existent, and therefore incompatible with a circular economy.

Why isn’t plastic from building materials recycled?

Additives (which may be toxic), fillers, adhesives used in installation, and products made with multiple layers of different types of materials all make recycling of plastic building materials technically difficult. Lack of infrastructure to collect, sort, and recycle these materials contributes to the challenge of recycling building materials into high-value, safe new materials.

Manufacturers have continued to invest in products that are technically challenging to reuse or recycle – initially cheaper due to existing infrastructure – instead of innovating in new, circular-focused solutions. Additionally, their investment in plastics recycling has been paltry. In 2019 BASF, Dow, ExxonMobill, Shell and numerous other manufacturers formed the Alliance to End Plastic Waste (AEPW) and pledged to invest $1.5 billion over the next five years into research and development of plastic waste management technologies. Compare that to the over $180 billion invested by these same firms in new plastic manufacturing facilities since 2010.5

Globally, regulations that discourage or ban landfilling of plastics have, unfortunately, not led to more recycling overall. Instead, burning takes the place of landfilling as the eventual end of life for most plastics.

Confusing rhetoric around plastic end of life options can make this story seem more complicated than it is.6

- “incineration” or “waste to energy” burns plastic for energy.

- “Plastic-to-fuel” or “gasification” or “pyrolysis” generates fuel. This output is rarely used for anything but burning due to the additional processing required to use for any other purpose.

- “Chemical recycling” could, in theory, lead to new plastic products. This technology is unproven and currently not a scalable solution. The outputs are often burned due to low quality.

Plastic waste burning, regardless of the euphemism employed, is a well established environmental health and justice concern.

Burning plastics creates global pollution and has environmental justice impacts.

In its exhaustive 2019 report, the independent, nonprofit Center for International Environmental Law (CEIL) documents how burning plastic wastes increases unhealthy toxic exposures at every stage of the process. Increased truck traffic elevates air pollution, as do the emissions from the burner itself. Burned plastic produces toxic ash and residue at approximately one fifth the volume of the original waste, creating new disposal challenges and new vectors of exposure to additional communities that receive these wastes.7

In the US, eight out of every 10 solid waste incinerators are located in low-income neighborhoods and/or communities of color.8 This means, in some cases, the same communities that are disproportionately burdened with the pollution and toxic chemical releases related to the manufacture of virgin plastics are again burdened with its carbon and chemical releases when it is inevitably burned at the end of its life.

The issue is global in scale. A recent report by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) found that “plastic waste incineration has resulted in disproportionately dangerous impacts in Global South countries and communities.” The Global Alliance for Incineration Alternatives (GAIA), a worldwide alliance of more than 800 groups in over 90 countries, has been working for more than 20 years to defeat efforts to massively expand incineration, especially in the Global South. GAIA members have identified incineration not only as an immediate and significant health threat in their communities, but also a major obstacle to resource conservation, sustainable economic development, and environmental justice.

Where do we go from here?

- Minimize production of virgin plastic. This should be the main focus of any plastic waste reduction plan and part of any comprehensive climate change initiative. Policies banning single use plastics or banning the construction of new plastic production facilities or facility expansions are two example solutions cited by GAIA.9 Less plastic means less waste and less material to incinerate.

- Invest in true circular economy initiatives. These may include, for example: extended producer responsibility programs, materials passports, materials disclosure, elimination of toxic chemical additives, product as a service models, and recycling facilities that support upcycling. By shifting industry investments toward circular economy infrastructure – instead of the nearly $200 billion investments in increased manufacturing and burning capacity – the plastic industry could start to be part of the solution of reducing plastic waste.

- When evaluating the “expense” of recycling and circularity vs business-as-usual, a fair calculation for the latter needs to include all costs associated with the production, use, and end of life impacts of plastics. That “cheap” vinyl floor is no longer so inexpensive when the full costs of global pollution and the health burdens of people of color and low income communities are included in the math. Externalities must be a part of the equation.

What is unquestionable is this: Today our only choices for plastic waste are to burn or landfill most of it. Expanding plastics production and incineration is a conscious decision to perpetuate well documented, fully understood inequity and injustice in our building products supply chain.

The folks at The Story of Stuff cover this in The Story of Plastics, four minute animated short suitable for the whole family. Comedian John Oliver tells the “R-rated” version of the story with impeccable research and insightful humor in his HBO show Last Week Tonight. It’s worth a look to learn exactly how the plastics industry uses the illusion of recycling to sell ever increasing volumes of plastic. Without manufacturer responsibility and investment, efforts to truly incorporate plastic into a circular economy have little chance of success.

SOURCES

- https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution

- https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/bee4ef3a-8876-4566-98cf-7a130c013805/The_Future_of_Petrochemicals.pdf See page 18, 30.

https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/us-energy-facts/ - https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab9e1e/pdf

- https://carpetrecovery.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CARE-2019-Annual-Report-6-7-20-FINAL-002.pdf

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jan/21/founders-of-plastic-waste-alliance-investing-billions-in-new-plants

- https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/False-solutions_Nov-9-2020.pdf

- https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Plastic-and-Climate-FINAL-2019.pdf

- https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d14dab43967cc000179f3d2/t/5d5c4bea0d59ad00012d220e/1566329840732/CR_GaiaReportFinal_05.21.pdf

- https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/False-solutions_Nov-9-2020.pdf

Coming Clean and EJHA teamed up with NRDC, Rashida Jones, and Molly Crabapple to tell the stories of vulnerable fenceline communities living near over 12,000 high-risk chemical facilities in America, urging action to protect their health and safety.

Equity

Equity