READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORTIn Louisiana, the factories that make the chemicals and plastics for our building products are built literally upon the bones of African Americans. Plantation fields have been transformed into industrial fortresses.

A Shell Refinery1 sprawls across the former Bruslie and Monroe plantations. Belle Pointe is now the DuPont Pontchartrain Works, among the most toxic air polluters in the state.2 Soon, the Taiwan-based Formosa Plastics Group intends to build a 2400-acre complex of 14 facilities that will transform fracked gas into plastics. It will occupy land that was formerly the Acadia and Buena Vista plantations, and not incidentally, the ancestral burial grounds of local African American residents, some of whom trace their lineage back to people enslaved there.3

Formosa has earned a reputation of being a poor steward of sacred places. Local residents have petitioned the Governor to deny permits for the facility, citing a long list of environmental health violations in its existing Louisiana facilities, including violations of the Clean Air Act every quarter since 2009.4 The scofflaw company was found to have dumped plastic pellets known as “nurdles” into the fragile ecosystem of Lavaca Bay on the Gulf of Mexico for years – leading to a record $50 million settlement with activists in that community in 2019.5

In the Antebellum South, formerly enslaved people often homesteaded on lands that were part of or near the plantations they once worked. They established communities of priceless historical and cultural worth, towns such as Morrisonville, Diamond, Convent, Donaldsonville, and St. James. Donaldsonville, Louisiana, is the town that elected Pierre Caliste Landry, America’s first African American mayor in 1868, just three years after the end of the Civil War. This part of Louisiana holds many layers of complex and deep African American history.

But in the last 75 years, since World War II, these communities have been overrun by petrochemical industry expansion enabled by governments wielding the clout of Jim Crow laws to snuff out any opposition or objection. Towns like Morrisonville and Diamond have been bought up to accommodate plant expansion. Residents have been forced to move out, their history and heritage literally paved over. It wasn’t until 1994 that the River Road African American Museum was established to preserve and present the history of the Black population as distinct from plantation representations of slavery. According to Michael Taylor, Curator of Books, Louisiana State University Libraries: “Only in the last few decades have historians themselves begun to appreciate the complexity of free black communities and their significance to our understanding not just of the past, but also the present.”6

Charting a New Way Forward—Together

Virtually every building product we use today contains a petrochemical component that originates from heavily polluted communities, frequently home to people of color. As the green building movement searches for ways to enhance diversity, inclusion and equity, how might it address the legacies of injustice that are tied to the products and materials we use every day?

Architect, Zena Howard, FAIA, offered insight in her 2019 J. Max Bond Lecture, Planning to Stay, keynoting the National Organization of Minority Architects national conference. Howard, known for her work on the design team for the breathtaking Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, most often works with people in communities whose culture and heritage were “erased” by urban renewal in the 1960’s. In Greenville, North Carolina, she looked to people from the historically African American Downtown Greenville community and Sycamore Hill Missionary Baptist Church Congregation to guide the planning and design process for a new town common and gateway plaza. The goal was not to “replicate” the lost community, but to bring its history and present day aspirations to life in the new design. In Vancouver, British Columbia, the development plan for a neighborhood founded by African Canadian railroad porters included an unprecedented chapter on “reconciliation and cultural redress.” The key to such efforts, according to Howard is co-creation and meaningful collaboration, whose Greek roots, she notes, mean “to labor together.”

How might we labor together to address environmental injustice when evaluating the overall healthfulness and equity of our building materials? The precedent of “insetting” suggests an approach.

Insetting has been pioneered by companies whose supply chains rely upon agricultural communities across the globe. According to Ceres, insetting is “a type of carbon emissions offset, but it’s about much more than sequestering carbon: It’s also about companies building resiliency in their supply chains and restoring the ecosystems on which their growers depend.”

In previous columns, I’ve addressed concerns about the social in industrial communities, e.g., proposals that perpetuate disproportionate pollution impacts when buying offsets rather than addressing emissions from a specific facility. Applying the “insetting” approach we might ask our materials manufacturers—and the communities that are home to the building materials industries—what steps can we take to encourage manufacturers to “labor with” communities seeking environmental justice, such as those along the Mississippi River? Can we, together, resurrect and restore their history, reconcile and redress historical wrongs, and build a healthier future for all?

Black History

Month Readings

To learn more about the history and present day conditions of Cancer Alley, see these excellent articles from The Guardian and Pro Publica: https://www.ehn.org/search/?q=cancer+alley

You can watch to Zena Howard’s J. Max Bond lecture, Planning to Stay, here: https://vimeo.com/378622662

You can learn more about the River Road African American History Museum here: https://africanamericanmuseum.org/

SOURCES

- Terry L. Jones, “Graves of 1,000 Enslaved People Found near Ascension Refinery; Shell, Preservationists to Honor Them | Ascension | Theadvocate.Com,” accessed February 18, 2020, https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/communities/ascension/article_18c62526-2611-11e8-9aec-d71a6bbc9b0c.html.

- Oliver Laughland and Jamiles Lartey, “First Slavery, Then a Chemical Plant and Cancer Deaths: One Town’s Brutal History,” The Guardian, May 6, 2019, sec. US news, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/may/06/cancertown-louisiana-reserve-history-slavery.

- Sharon Lerner, “New Chemical Complex Would Displace Suspected Slave Burial Ground in Louisiana’s ‘Cancer Alley,’” The Intercept (blog), December 18, 2019, https://theintercept.com/2019/12/18/formosa-plastics-louisiana-slave-burial-ground/.

- Louisiana Bucket Brigade, “Sign the Petition,” Change.org, accessed February 25, 2020, https://www.change.org/p/governor-edwards-stop-the-formosa-chemical-plant.

- Stacy Fernández, “Plastic Company Set to Pay $50 Million Settlement in Water Pollution Suit Brought on by Texas Residents,” The Texas Tribune, October 15, 2019, https://www.texastribune.org/2019/10/15/formosa-plastics-pay-50-million-texas-clean-water-act-lawsuit/.

- LSU Libraries, “Free People of Color in Louisiana,” LSU Libraries, accessed February 18, 2020, https://lib.lsu.edu/sites/all/files/sc/fpoc/history.html.

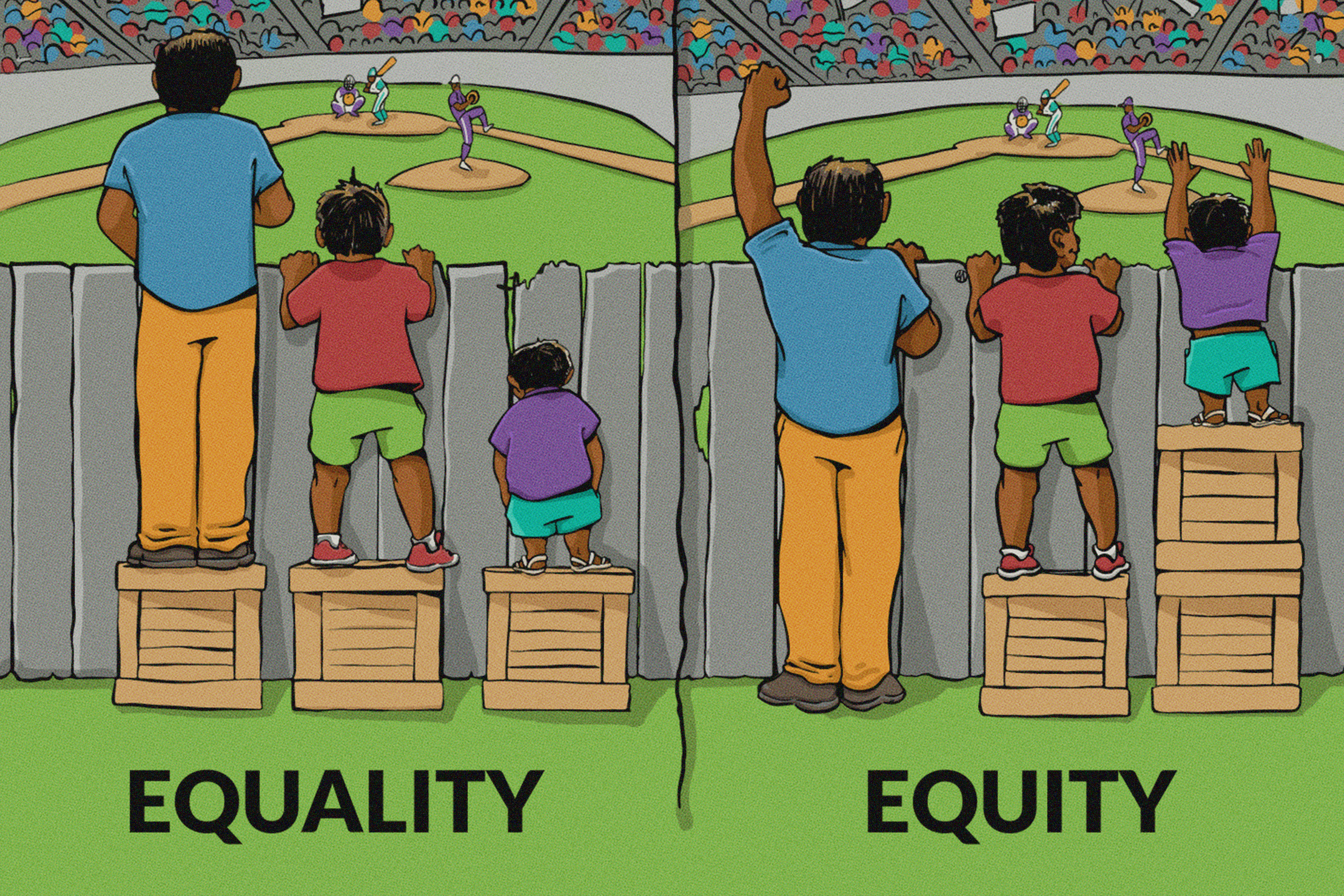

A whole lot of meaning is packaged in the word equity—a term Webster’s defines as “fairness or justice in the way people are treated.” However, the easiest way to understand equity is often through pictures, like the one below.

While this photo considers height as an inequity, in real life, income, access to food and health care are often at the heart of equity discussions. Surprisingly, a critical topic often overlooked in the equity discussion is where we spent 90 percent of our lives—in buildings.1

Oregon Metro, otherwise known simply as Metro, released a report discussing toxics reduction and equity. Its section on building materials connects building materials and equity, calling attention to the need to reduce community exposure to toxic building materials in an equitable manner. Building materials seem harmless and inert in our homes, offices, schools, or cafes. But in 1991, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) characterized indoor air pollution as “one of the greatest threats to public health of all environmental problems”.2

A large proportion of indoor air pollution stems from building materials.3 In particular, asthmagens are of highest concern and contribute to indoor air pollution through the release of chemicals from the surface of building finishes.4 For example, carpet, furniture and wall decor release chemicals through degradation or abrasion.5 The chemicals end up in dust in our homes and can enter our bodies through the lungs, skin or mouth.6 Volatile organic compounds emitted from paints are also of concern.7 In fact, a study of children in Australia showed a strong association among indoor home exposure to VOCs and increased risk of asthma.8 Over 70 percent of building material asthmagens identified by Healthy Building Network (HBN) researchers are not covered by leading indoor air quality testing standards.9 These hazardous wastes and products used in building materials disproportionately affect historically marginalized communities of color, children and low-income families.10

Equity in housing is especially important for many families with low incomes who live in multifamily housing.11 Multifamily housing often poses challenges to achieving better air quality as pollutants easily travel between units due to inadequate ventilation. Residents are usually unable to improve building infrastructure themselves.12

Incorporating building materials into the equity discussion is only part of the solution. Product testing for chemicals of concern, biomonitoring, community health impact research, chemicals research, advocacy and education all stand to make a larger collective impact.13

For funders looking to increase diversity and equity initiatives in their grant making, the building industry provides a blooming landscape to foster substantial impact within communities. Here are some key questions to consider when funding proposals:

- What is the specific toxics reduction action?

- Are there particular populations or communities impacted more than the general population by the chemical/product/system in question?

- Does the action consider and address the structural barriers and existing resources available to a population?

- Does the recommendation ameliorate the disparity or gap in accessing resources for a marginalized community?

So often, sustainability standards and initiatives are cost prohibitive, developed for those with the most access and resources, in hopes that “someday” the solutions will trickle-down. In the meantime, children and the populations with the lowest income continue to bear the burden of toxic exposures and preventable health consequences. Habitable’s Informed™ healthy product guidance is changing that old, unsuccessful paradigm. Our resources will result in healthier products for everyone, and amplify the prospect for a healthier planet.

Visit informed.habitablefuture.org to join the movement towards a healthy future for all.

SOURCES

- Cuneo, Monica et. al. Toxics Reduction and Equity: Informing actions to reduce community risks from chemicals in products. Oregonmetro.gov, 2019. August 14, 2019. https://www.oregonmetro.gov/toxics-reduction-and-equity-study

- Ibid.

- Environmental Protection Agency. “Fundamentals of Indoor Air Quality in Buildings.” Indoor Air Quality, 1 Aug. 2018, www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/fundamentals-indoor-air-quality-buildings#Factors.

- Lott, Sarah, and Jim Vallette. Full Disclosure Required: A Strategy to Prevent Asthma Through Building Product Selection. Healthy Building Network, December 2013. August 14, 2019. https://habitablefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/93-full-disclosure-required-a-strategy-to-prevent-asthma-through-building-product-selection.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Singla, Veena. Toxic Dust: The Dangerous Chemical Brew in Every Home. Natural Resources Defense Council, September 13, 2016. August 20, 2019. https://www.nrdc.org/experts/veena-singla/toxic-dust-dangerous-chemical-brew-every-home

- Lott, Sarah, and Jim Vallette. Full Disclosure Required: A Strategy to Prevent Asthma Through Building Product Selection. Healthy Building Network, December 2013. August 14, 2019. https://habitablefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/93-full-disclosure-required-a-strategy-to-prevent-asthma-through-building-product-selection.pdf.

- Rumchev, K, et al. Association of Domestic Exposure to Volatile Organic Compounds with Asthma in Young Children. Thorax, BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, 1 Sep. 2004. August 14, 2019. http://thorax.bmj.com/content/59/9/746.

- Lott, Sarah, and Jim Vallette. Full Disclosure Required: A Strategy to Prevent Asthma Through Building Product Selection. Healthy Building Network, December 2013. August 14, 2019. https://habitablefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/93-full-disclosure-required-a-strategy-to-prevent-asthma-through-building-product-selection.pdf.

- Cuneo, Monica et. al. Toxics Reduction and Equity: Informing actions to reduce community risks from chemicals in products. Oregonmetro.gov, 2019. August 14, 2019. https://www.oregonmetro.gov/toxics-reduction-and-equity-study

- Ibid.

- Hayes, Vicky et al. Evaluating Ventilation in Multifamily Buildings. Home Energy Magazine, August 1994. August 14, 2019. www.homeenergy.org/show/article/nav/ventilation/id/1059.

- Cuneo, Monica et. al. Toxics Reduction and Equity: Informing actions to reduce community risks from chemicals in products. Oregonmetro.gov, 2019. August 14, 2019. https://www.oregonmetro.gov/toxics-reduction-and-equity-study

A week after the US Green Building Council’s (USGBC) Technical Science Advisory Committee determined that PVC was one of the most unhealthy building materials in part due to occupational exposures to vinyl chloride, the federal Chemical Safety Board (CSB) found that a massive release of vinyl chloride led to the explosion that killed 5 workers at a PVC factory in Illiopolis, Illinois on April 23, 2004.

The CSB Investigation Report is made all the more relevant to green building professionals in light of the USGBC’s finding that PVC flooring ranked absolute worst in both human health and environmental factors compared to the alternatives reviewed. The destroyed factory, owned by Formosa Plastics, had been a major supplier of vinyl resin for Armstrong floors.

The CSB is the industrial equivalent of the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), the agency that rushes investigators to the scene of plane crashes, train derailments and the like. [1] The CSB’s March 6, 2007 report found among other things that the cause of this accident, “inadvertently draining a reactor, is a serious hazard in the PVC manufacturing process.” [2] Indeed just 60 days before the fatal explosion, workers at the same facility accidentally released an undisclosed amount of vinyl chloride. The report also notes that 8,000 pounds of vinyl chloride were released by accident in June 2003 at the company’s Baton Rouge, LA facility. [3] A year after the explosion, in May 2005, another 2,500 pounds of vinyl chloride were accidentally released from the company’s Delaware City, DE location. [4] Each release was caused by the same problems which led to the catastrophe at the Illiopolis facility in April 2004. Other PVC factories owned by Formosa have also suffered catastrophic explosions in the recent past. [5]

The chemical at issue, vinyl chloride, is a human carcinogen whose total danger is believed by many to be underestimated by the EPA. A 2005 study in the peer reviewed journal American Health Perspectives found that the EPA employed discredited scientific practices at the behest of the chemical industry in order to lower estimates of vinyl chloride’s cancer potency by tenfold. [6]

The USGBC’s study of PVC found it “consistently among the worst materials for human health impacts” based upon exceedingly conservative estimates of impact. To understand how conservative, consider that its evaluation of PVC only accounted for exposures from normal operations to workers in the factory and neighbors at the fenceline. The health impacts of the extraordinary accidental releases from Formosa’s facilities described above — and the deadly explosions that can follow as at Illiopolis — are beyond the reach of tools like LCA and risk analysis.

This CSB report further underscores the significance of the USGBC’s decision to be guided by the Precautionary Principle in its evaluation of green building materials and to fully consider the impacts of manufacturing processes on production workers. It is the essence of precaution to avoid hazards and risks that are avoidable. So remember this the next time you specify pipe, roofing membranes, wall coverings and especially flooring: the chemical that killed those 5 men in Illiopolis is essential and unique to only one material you are considering: PVC plastic, also known as vinyl. [7]

SOURCES

- The CSB is an independent federal agency charged with investigating industrial chemical accidents. The agency’s board members are appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. CSB investigations look into all aspects of chemical accidents, including physical causes such as equipment failure as well as inadequacies in regulations, industry standards, and safety management systems. The Board does not issue citations or fines but does make safety recommendations to plants, industry organizations, labor groups, and regulatory agencies such as OSHA and EPA.

- US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board Investigation Report, Formosa Plastics Corp., Illiopolis, Illinois, April 23, 2004 p. 29. http://www.csb.gov/completed_investigations/docs/FormosaPlasticsIlliopolisReport.pdf

- Ibid. p. 28

- Ibid. p. 29

- http://abclocal.go.com/wpvi/story?section=nation_world&id=3514274 [link no longer available]

- Jennifer Beth Sass, Barry Castleman and David Wallinga. “Vinyl Chloride: A Case Study of Data Suppression and Misrepresentation,” Environmental Health Perspectives, published online 24 March 2005, doi:10.1289/ehp.7716, http://www.ehponline.org/members/2005/7716/7716.html

- To be sure, vinyl chloride is not the only avoidable risk in the production of flooring, or plastics, or materials generally. However, the risk of explosion is only one of the negative environmental health consequences of vinyl chloride whose use is both essential and unique to PVC plastic. Related impacts include dioxin emissions from manufacture and fire, the use and release of toxic additives such as cadmium and lead stabilizers and phthalate softeners, and the threats associated with the production of massive quantities of chlorine gas as the basic building block of vinyl chloride production. These factors lead HBN to the conclusion that PVC is the worst plastic for the environment.

Equity

Equity