Policy Brief + Recommendations

Policy Brief + RecommendationsAs sustainability professionals, we face a sobering reality: every day, materials are extracted, manufactured, used, and discarded at a rate that outpaces the Earth’s ability to regenerate.1

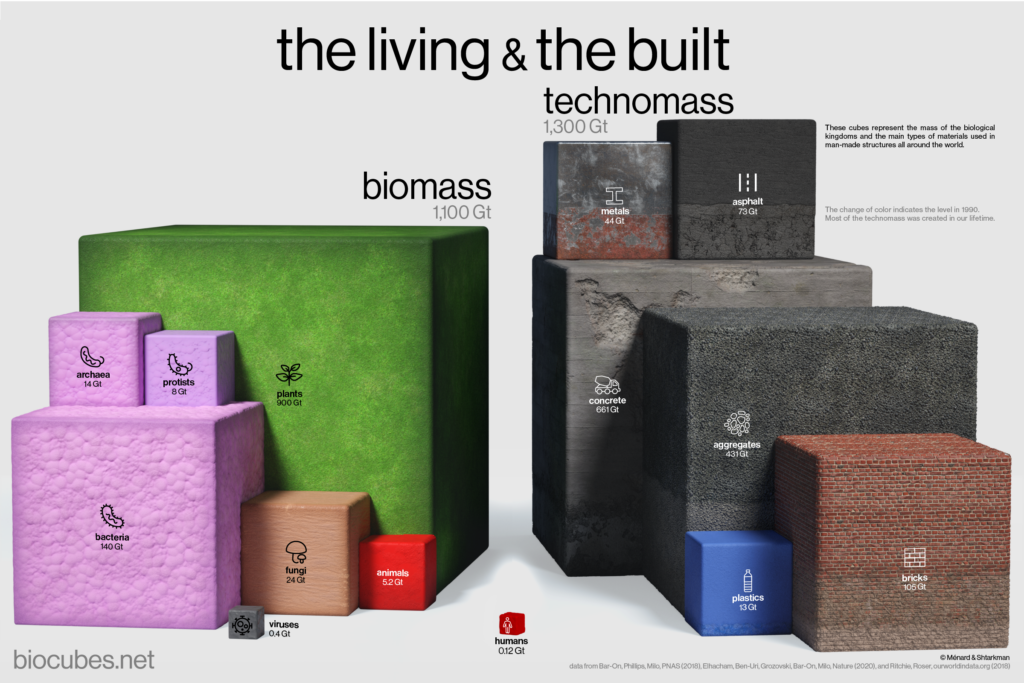

Our global ecological footprint has reached unprecedented levels.2 Humanity’s total material demand–our buildings, roads, machines, and products–now outweighs all living things on Earth.3 These aren’t just statistics, they are a wake-up call for everyone working in sustainability and materials management.

I’ve spent the last two decades working on climate impact and waste assessment for companies and governments across the United States, and have watched as local sustainability efforts have flourished while the global environmental picture becomes more and more grim. One of the biggest challenges I’ve seen is that the traditional metrics of sustainability–carbon footprints, waste reduction targets, efficiency gains–are designed to drive localized, regional progress. These measures of ‘success’ overlook a crucial reality: when we cut costs and resource use in one place, consumption often increases somewhere else in the world. As sustainability professionals leading the charge for a more just and regenerative future, our biggest challenge today is not merely advancing existing measures of ‘success.’ Instead, we must fundamentally reimagine our relationship with an economic system that prioritizes growth above all else and shift toward one that values health through balance and harmony with nature. When the planet is healthy, we are healthy.

This reality is pushing sustainability leaders to ask harder questions: How can we create genuine prosperity while respecting Earth’s ecological limits? What would it look like to build a materials economy that serves both people and planet? The answers require us to examine not just how we manage materials, but how we think about growth itself.

The Limits We Face

There is already a great body of knowledge on “the ability to thrive as a society, while respecting biophysical limits.”4 This wisdom, however, stems from ways of living and being that do not center economic size as a marker of societal well-being. In contrast, the goal of most economies around the world today is to simply grow.

The Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy recently showed that the world’s seven largest economies have enshrined “economic growth” as a goal in and of itself, detached from any kind of social or well-being metrics.5 But economic growth doesn’t happen in a vacuum: our environment, people, and communities are all impacted by macroeconomic decisions. Considering this, three key issues emerge that challenge our perception of growth’s ‘success’:

- First, there are ecological constraints. The global economy must operate within Earth’s ecological limits – thresholds for resource extraction, land use, and pollution that we are currently exceeding. We simply cannot sustain current levels of ecological demand.

- Second, there are efficiency limitations. Our current materials economy is deeply interconnected: when one company reduces its material use, the saved resources are typically invested into other parts of the economy, driving further growth and consumption. Time and experience have proven that efficiency gains do not actually reduce resource use, unless they are paired with a commitment to limit demand.6

- Finally, there are equity concerns. The benefits and burdens of our materials economy are not shared equally. While ~10% of global society controls 90% of the wealth,7 billions still lack access to basic resources for a dignified life.,8,9 Shifting our economy towards alternative and more efficient technologies alone will not address this fundamental imbalance.

Let’s dive a little deeper into how these issues affect people and our planet:

Earth’s Limited Resources

We must acknowledge and work within Earth’s limits to economic growth. Our collective ecological demands have been outpacing the regenerative capacity of our planet since the 1970s.10 Globally, we’ll need to shrink the total size of that demand in order to bring our footprint back in balance with nature.

Humans’ fossil-fueled economy has pushed the global climate past its natural limits: recent highly visible weather events related to our changing climate are symptomatic of pushing past ecological constraints. This isn’t unique to climate–all natural systems have boundaries and it is now time for us to work within the boundaries of a healthy, thriving planet.

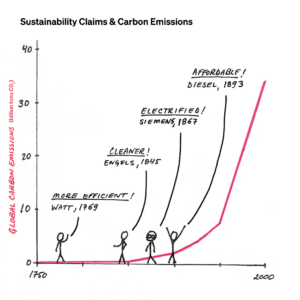

Beyond the Efficiency Trap

Efficiency gains must be coupled with limits on total ecological demand. To date, the most common approach for reducing ecological demand has been introducing more efficient technologies: new power plants, more fuel-efficient engines, and ever-smaller computing devices deliver their services with less material input per unit of output. But when we reduce resource use through efficiency, a growth-focused economy uses those saved resources to consume more elsewhere. It’s like squeezing a balloon – the air just moves to a different spot.

The factors that drive ecological change on planet earth are connected to commodity flows that operate across political boundaries, meaning reduced demand in one part of the economy is easily offset by increased consumption in another. For example, the U.S. has reduced its fossil fuel demand over the past two decades, but the global economy has easily reallocated those savings in the planetary push for economic growth. In practice, efficiency gains are often redirected into making more products, feeding a cycle of continuous growth that ultimately leads to more extraction, more waste, and more strain on our planet’s systems.

Illustration by John Mulrow, PhD

Centering Equity

Sustainability strategies must prioritize equity alongside environmental goals. Our traditional, Western understanding of economic growth prioritizes gain for a small subset of the global population. Even if economic growth were intended to benefit all humanity, it has failed in practice.

In his book Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World, Jason Hickel presents data showing that while global GDP per capita increased fivefold between 1980-2016, this growth was highly unequal, with only the wealthiest 10% of people seeing their incomes grow at or above this rate. The richest 1% gained disproportionately more, while the vast majority of people experienced minimal economic benefits despite overall growth.11 This pattern repeats even within high-income countries, as Matt Orsagh, a post-growth finance advocate, has pointed out. In the US, it is also the wealthiest 10% of people that have accumulated the majority of economic growth for themselves in recent decades.12 Clearly, there is a need to rebalance and redefine economic flows so that when and where growth happens it benefits those truly in need.

New Metrics for a Healthy, Thriving Planet

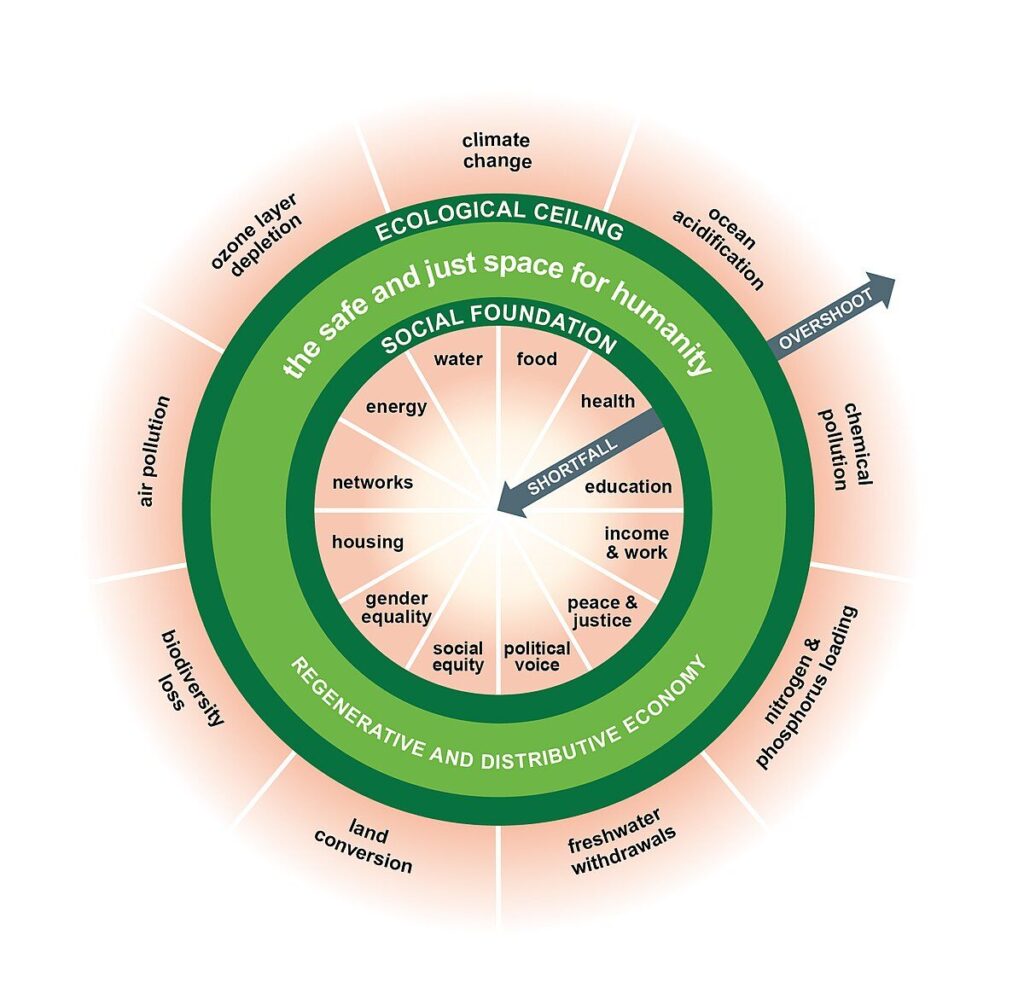

Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics concept has provided a framework for seeking social and environmental sustainability without prioritizing growth for growth’s sake. The doughnut diagram represents a safe and just operating space for humanity, with the inner boundary representing minimum requirements for human well-being (the social foundation), and the outer boundary representing planetary systems impacted by economic activity (ecological ceiling).

The reality is that social foundation metrics are not being met for many across the world and yet we are exceeding planetary boundaries, atmospheric CO2 levels being just one of several ecological emergencies. Raworth’s work has been effective at helping sustainability professionals break from efficiency as a marker of environmental impact reduction, instead pairing planetary-scale impact metrics with socioeconomic ones like equity and access.

Well-Being

New ways of thinking about growth bring fresh focus to the fundamental question of what truly constitutes ‘wealth’ versus ‘well-being.’ While social and ecological metrics provide important global context, numbers alone won’t be enough to persuade a critical mass of environmental advocates and professionals to break from the commitment to growth embedded in most sustainability plans.

To orient away from growth, we’ll need enticing ways to live the good life with less economic throughput. That’s why this reimagining of economics prompts psychological inquiries into the question “how much is enough?”, explorations of indigenous ways of knowing and being, and long-standing critiques of economic development goals aimed at increasing Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as the sole marker of societal well-being.

A Future Beyond Growth

As a sustainability professional on this journey, I constantly remind myself that the path beyond growth is still being trodden. It extends from many places in humanity’s past, and the justifications for redefining growth are not solely technical; ongoing ecological degradation is not in need of ever-more refined climate, energy, and economic forecasting techniques. Economic growth is a social and political commitment embedded in daily life. Challenging it necessitates action in both personal and professional spheres.

Here are some steps to begin:

- Foster Dialogue: Sometimes asking questions like “How much is enough?” or “How can we use less?” are enough to spark a conversation that questions the growth paradigm in a constructive way. You can share and build on writings that critique growth–influential works like Doughnut Economics by Kate Raworth, Less is More by Jason Hickel, and Braiding Sweetgrass and The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer provide valuable perspectives. The Degrowth Institute’s discussion toolkit also offers practical resources for sparking conversations.

- Integrate Global Contexts: Add a global economic perspective to your projects. For example, consider what happens to financial and resource savings enabled by efficiency measures. Can these savings be reinvested in ways that increase equity or protect the environment, instead of prompting more consumption? What are the risks that resource demand resurfaces elsewhere in the economy? Asking such questions can shift the focus toward systemic change.

- Stay Motivated: Breaking from growth-centric paradigms is crucial for self-regulating our economy within planetary boundaries. Although unprecedented in modern times, this shift promises significant social and environmental benefits and recent summaries in Ecological Economics offer concrete policy proposals.

For those based in the U.S., various organizations—including the Post Growth Institute, CASSE, Arketa Institute, and DegrowNYC—are advancing the movement through discussion, debate, and action.

Sustainability’s next great challenge is to build a smaller, fairer economy that ensures a thriving future for all within the limits of our one shared planet.

Remember, the goal isn’t perfection—it’s progress toward a materials economy that works for both people and planet. Each step we take builds momentum for broader change. The transition to balance our ecological footprint won’t be easy, but it’s essential for a shared future. As sustainability professionals, we have the opportunity–and responsibility–to lead this transformation. By taking these concrete steps within our organizations, we can help create a future where innovation serves the goal of true sustainability rather than limitless growth.

About the Author

John Mulrow, PhD

John Mulrow is Executive Director of the Degrowth Institute and Adjunct Assistant Professor of Environmental and Ecological Engineering at Purdue University. His work is focused on improving environmental assessment methodology through perspectives that prioritize social equity and limits to growth. He holds a PhD in Civil Engineering from University of Illinois Chicago and a BS in Earth Systems from Stanford University.

DEFINITIONS

Ecological footprint: Economic goods and services require inputs that originate from natural systems

Ecological resources include raw materials such as water, fuels, plants, and mineral ores and natural functions such as water flow, photosynthesis, and atmospheric circulation.

Ecological demand is the ecological footprint required to meet human wants and needs.

Ecological constraints are the limits of demand, beyond which certain natural systems become destabilized. These limits can be characterized in many ways but we prefer the Stockholm Resilience Institute’s planetary boundaries framework.

FOOTNOTES

- https://footprint.info.yorku.ca/data/

- https://footprint.info.yorku.ca/data/

- biocubes.net

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/exploring-environmental-violence/degrowth-perspective-on-environmental-violence/561C3D8FA140F8EB1EFCE6EDBEE8A46E

- https://steadystate.org/the-economic-priority-of-the-seven-wealthiest-countries-more-wealth/

- See “Banking sustainable consumption’s savings” in https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388491654_Degrowth_and_Sustainable_Consumption

- https://www.credit-suisse.com/media/assets/corporate/docs/about-us/research/publications/global-wealth-databook-2022.pdf

- https://www.activesustainability.com/environment/natural-resources-deficit/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2542519624000421

- https://footprint.info.yorku.ca/data/

- Hickel, J. (2022). Less is more: How degrowth will save the world. Penguin Books.

- Orsagh, M. (2024, December 16). Degrowth is the Answer | Substack. https://degrowthistheanswer.substack.com/

In 2024, Habitable experienced significant growth and transformation. Our strategic rebrand from Healthy Building Network to Habitable marked a pivotal shift in how we communicate and achieve our mission. We expanded our organization’s historic focus on green chemistry and on the lifecycle effects of toxic chemicals in building products to scale our results and achieve pollution reduction, climate change mitigation, and equity and environmental justice. Through new and growing partnerships with Beyond Petrochemicals, Cooper Carry architecture and design, and many others, we’ve positioned ourselves to tackle increasingly complex challenges at the intersection of the materials economy and planetary health, ensuring a habitable future for all. Check out our 2024 Year in Review for more information.

Key Milestones That Shaped Our Year

Redefining Our Identity

This year, our transition to Habitable represented more than a name change—it embodies our new vision: All people and the planet thrive when the materials economy is in balance with Earth’s natural systems. . This new identity reflects our team’s capabilities and our evolution towards a more comprehensive approach to creating a path to planetary health. The rebrand has enabled us to activate our mission more broadly, setting the stage for deep engagement with new audiences, and more effective communication of our vision for a healthier planet.

Expanding Our Research Footprint

In 2024, Habitable’s research revealed critical connections between building materials and planetary health. Our groundbreaking policy brief, Buildings’ Hidden Plastic Problem, reported a startling reality: the building and construction sector is the second-largest consumer of plastics globally, behind packaging. This research advances our work among global audiences, reshaping the conversation around plastic pollution by highlighting a crucial opportunity to reduce fossil fuel demand through better building practices. We deepened this investigation through our fact sheet Our Disposable Plastic Buildings, developed in partnership with Perkins&Will, and engaged industry leaders through our webinar Buildings Contribution to Global Plastic Crisis.

Beyond our pioneering work on plastics, we expanded our research to address planetary health challenges across various scales. Our report, Advancing Health and Equity through Better Building Products, highlights examples of leaders within and beyond Minnesota’s built environment who are taking action toward safer material choices and provides guidance on how the real estate industry can begin working towards a healthier future. A joint article with SERA Architects, Healthy Materials and the Constitutional Responsibility for Health and Wellbeing, emphasizes the need to prioritize solutions that address both climate change and toxic pollution in frontline communities. Meanwhile, our webinar Redesigning the Materials Economy for People and Our Planet convened global thought leaders to explore systemic solutions to these same challenges. These interconnected initiatives have positioned Habitable at the forefront of research linking building materials to both environmental and human health outcomes, setting the stage for even deeper investigations in 2025.

Building Stronger Partnerships

Transformative partnerships defined our work in 2024. With support from Beyond Petrochemicals, we launched an innovative research exploring the significant human and environmental impacts from plastics use in the building sector. This collaboration enabled us to highlight the necessity of including the built environment in plastic policy considerations, marking our entry into the global effort to reduce plastic pollution, including a partnership with Dr. Bethanie Carney Almorth, who is involved in the Global Plastics Treaty negotiations. Our growing network of partners—from universities, corporations, government agencies to NGOs—has enriched our approach and expanded our capacity to drive meaningful change.

Growing Our Community

The Habitable team expanded in 2024, welcoming Priya Premchandran, a seasoned sustainability practitioner with over 15 years of experience at the intersection of the built environment and human health, who has already shaped our InformedTM initiative in profound ways. Our presence at major conferences and leading firms across the country–including Greenbuild, Verge, CannonDesign, AIA MN, USGBC Green Schools and more–positioned us within crucial discussions about material health impacts, while our convening a community of practice in Minnesota participation helped forge new connections with built environment innovators, like the Lower Sioux Community. These engagements have not only elevated our voice in key conversations but have also informed our strategic direction.

Looking Ahead

2025 marks Habitable’s 25th anniversary year. The foundations we’ve built in 2024–our strategic rebrand, renewed research focus, strengthened partnerships, and expanded community–position us to pursue our mission and vision with renewed vigor.

The challenges facing planetary health demand bold action and fresh thinking. Through our work, Habitable remains committed to catalyzing the transformative changes needed for a more sustainable and equitable future.

If you have appreciated our resources and efforts, please consider a donation. We look forward to working with you in the new year!

Safer States is a national alliance of environmental health groups led by state-based organizations working towards a healthier and more just future.

By addressing critical issues such as toxic chemicals, plastics, and climate change, Safer States empowers collective action through its extensive network and capacity-building initiatives. The organization’s resources focus on ensuring clean air and water, holding polluters accountable, and promoting the development of safer consumer products. Safer States offers valuable tools and support for creating safer solutions for human health and the environment, including a bill tracker that identifies state policies that move the needle toward achieving a healthier world.

SERA’s former Sustainability Manager Beth Lavelle recently wrote an op-ed in the Portland Business Journal that has inspired some interesting conversations in the office about architects’ and designers’ responsibility to safeguard the public’s right to a healthy and safe environment.

Recent court cases (Held v. Montana, Juliana v. U.S.) have led to decisions that directly tie climate change to constitutional rights. The Held decision found that the state of Montana, “. . . is failing to meet their affirmative duty to protect Plaintiffs’ right to a clean and healthful environment, and to protect Montana’s natural resources from unreasonable depletion.” Beth’s thought-provoking question is: If the U.S. government can be found at fault for depriving the public of a clean and healthy environment, does the building sector risk similar liability?

Beth’s piece focuses on the need for greater regulation to require the use of green building strategies, and I argue that the same is true for healthy building materials. When designers, builders, and developers choose toxic materials, they risk liability for the harm they cause to the users of their spaces as well as those involved along the supply chain.

As architects and designers, we bear a profound responsibility to shape the world around us, not just aesthetically, but also ethically and responsibly. Our designs don’t exist in isolation; they interact intimately with the lives of individuals, communities, and the environment. In this regard, the materials we specify play a pivotal role in shaping the health and safety of the spaces we create.

The Challenge: Competing Priorities and the Bottom Line

Cost & Performance:

From a material cost point of view, healthier materials can often be comparable to the price points of more toxic materials. However, the time and labor hours spent researching, validating, and tracking healthier material selections and certifications can significantly add to total project costs, and this is often a barrier to designers’ selection process. The reality is, it takes less time to select finishes when we’re only focused on performance and aesthetics, without the added layer of validating and certifying material health properties too.

There’s little motivation for clients to choose healthy materials:

Clients are faced with a variety of pressures and priorities, like staying within budget and getting the project done on schedule. They also might assume that the government is regulating and eliminating toxic products from the market – which is not the case. Without awareness and the drive from company values, regulatory requirements, or consumer demand, there may be little motivation for clients to choose healthier materials, especially in any case where there is a cost premium. As much as designers can advocate for healthier materials on our projects, we are often limited by project priorities and available project fee hours.

Navigating the complexities of certifications–information overload:

With all of the project responsibilities designers must juggle, and a vast landscape of material certifications with different levels of rigor and limited considerations beyond the use phase, it can be overwhelming and burdensome to understand and navigate healthier material product selection. After all, we are not scientists!

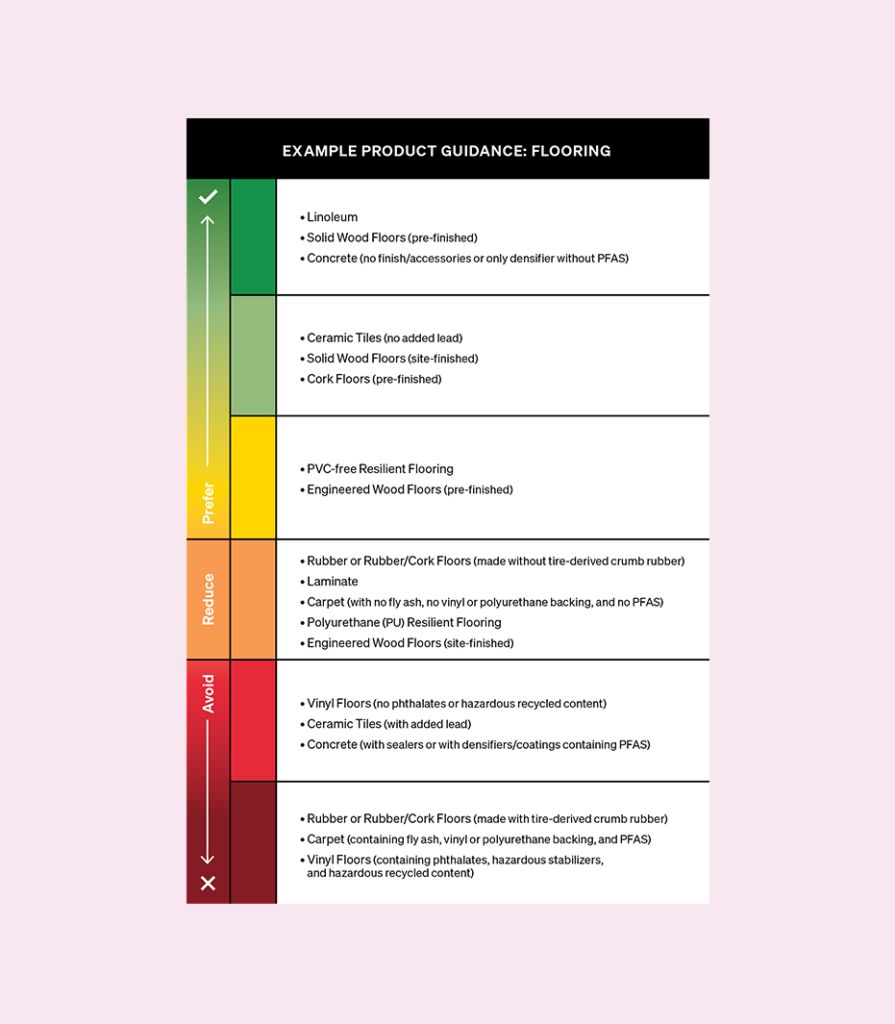

Useful Options and Better Strategies

The good news is, we are beginning to see more resources to help designers make healthier product decisions, regardless of client priorities and certification goals. One of SERA’s go-to resources is Habitable’s Informed Product Guidance. The intuitive red-to-green color ranking compiles decades of research to summarize key health impacts and considerations across the life-cycle of common building materials.

The first step? Avoid selecting materials in the red categories, and opt for yellow or green instead. Want to learn more? Expand the drop-down menus to read about the health impacts of that material type. Importantly, this tool does not suggest specific manufacturers or products. Instead, it provides guidance about types of materials, making it easier for designers to prioritize what to look for when generating finish palettes and selecting specific products. Identifying safer building product types means that designers don’t have to do as much research or memorize long lists of materials. It’s like shopping the perimeter at grocery stores, where the fruits, vegetables, and other fresh goods are usually laid out. The center aisles are where all the candy, super-processed snacks, and other less natural products lurk–if you stay out of that area, you can be confident that you’ll be eating relatively healthful foods, even without knowing the latest updates on ingredients or additives. (The almonds in that candy bar may be certified organic, but we all know it’s not a very healthy option, right?). Habitable’s Informed Product Guidance can help get you to the right aisles—and know that you’ll be specifying products that are generally safer for building occupants, workers, and communities.

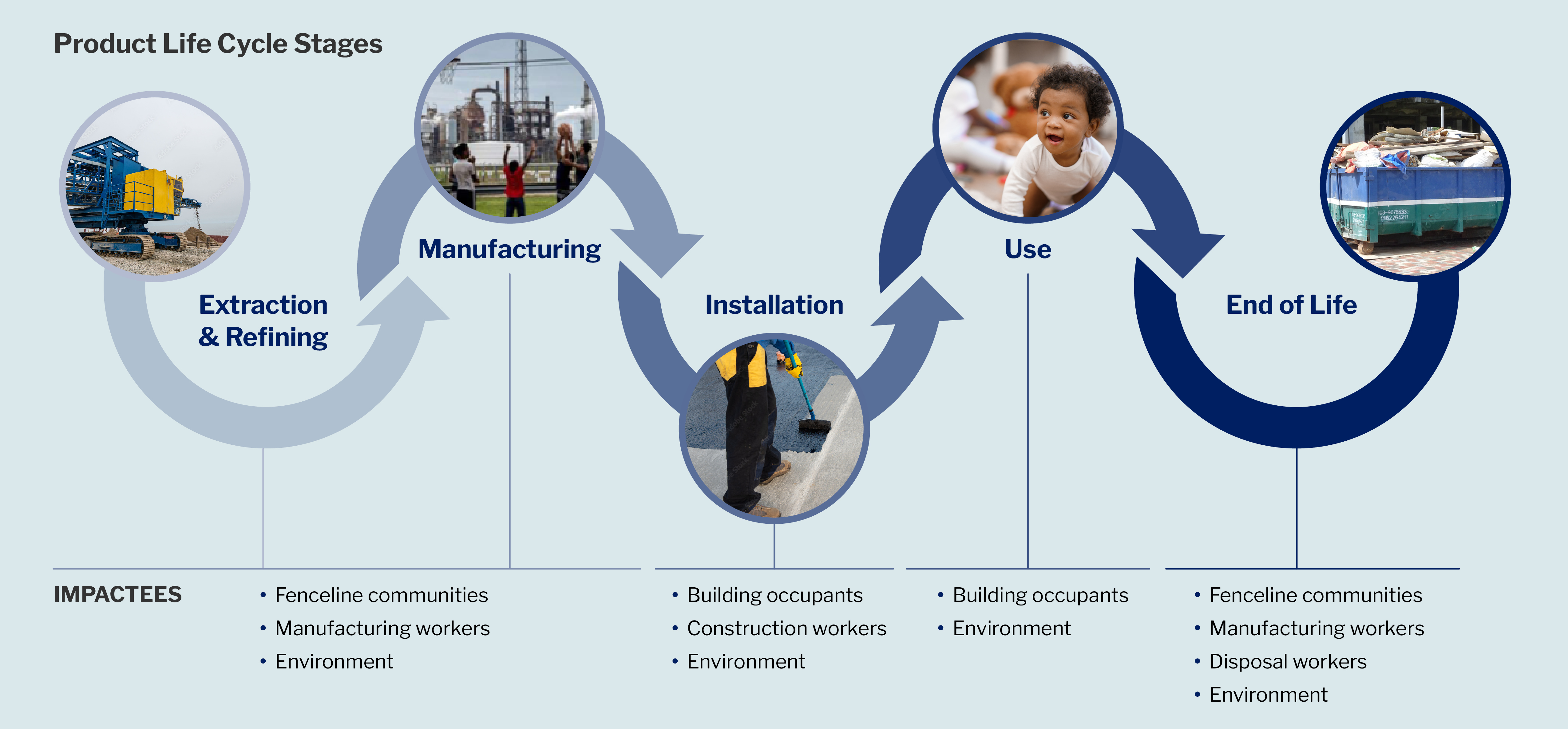

Considerations from the science side: looking at materials through the life-cycle lens

For example, it’s common for housing developers to opt for Luxury Vinyl Tile (LVT) due to its durability, easy installation, and low first cost. However, we can see by looking at the Informed Product Guidance that LVT is in the red category. Phthalates, chemicals known to disrupt the hormonal system, were once commonly found in LVT. While in recent years we’ve seen more and more phthalate-free LVT products become available, even “better” vinyl is still not a preferred material! This is because of the toxic processes required to make polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and the toxic pollution created when it’s disposed of. And let’s not forget, vinyl is a form of plastic derived from fossil fuels, so its use continues our reliance on the polluting fossil fuel industry at a time when we are electrifying our buildings to decrease fossil fuel use.

What does that all really mean? Not only can building products have negative health impacts on the daily occupants of a space, they often impact installers, factory workers handling the material production, and the communities living near those processes. And unfortunately in the case of housing, renters are likely unaware of any of this when selecting a place to live. Which brings us back to the dilemma for designers: is it really ethical to specify a material when we know its negative health impacts? And if we make the decision to take care in our specifications, how can we encourage our clients to approve healthier alternatives?

The Long-Term Solution: Increased Demand and Regulation

From our perspective, it remains essential for designers and building professionals to make a commitment to disrupt the status quo, prioritize implementing better product selections on our projects, and have meaningful conversations with clients about the importance of healthier and non-plastic materials. In other words, continue to make noise! At the same time, what’s really going to make a change in the industry is an increase in demand for healthier products.

One avenue for increased demand can come from consumers. Apartment dwellers, home owners, office workers, hotel guests, and restaurant-goers (and so on!) have the right to know whether a material or product contains toxic substances or uses them in manufacturing. More often than not, consumers are in the dark about the toxics found in building products due to lack of visibility and awareness. Much like nutrition labels found on food products, it’s reasonable to expect that building materials and finishes in the public marketplace could include clear labels like hazard pictograms or ingredients lists. At a minimum, this may help consumers start to have some visibility into the harmful chemicals used in the built environment. Imagine a world where healthy buildings, spaces, and materials are desired and actively sought-out by the general public! That just might be enough incentive to drive market change.

While visibility and awareness may increase some demand for healthier materials, the burden of change is broader than that. Arguably, the biggest agent of change will come from government regulation to reduce harmful substances used in consumer products in the first place. For example in the EU, REACH Regulation aims to protect health and the environment against harmful chemicals. And the Classification, Labeling and Packaging (CLP) Regulation ensures hazards posed by chemicals are clearly communicated when placed on the market, enabling consumers to make informed decisions when purchasing or using products. It is critical that the U.S. government begins to take responsibility for policies and regulation that better protect citizens and the environment, and boost innovation for safe and sustainable chemicals.

Looking forward, we envision a world where healthier materials will be actively sought out by consumers, more strictly regulated at the government level, and ultimately become the baseline standard for all construction and building materials and finishes. For now, we must continue to advocate for change, educate ourselves (using tools like Habitable’s Informed Product Guidance to step up from red-ranked products!), and intentionally make healthier product selections on our projects. This responsibility isn’t just a passing concern; it’s a duty we owe to ourselves, to each other, and to future generations.

This episode featured Teresa McGrath, the Chief Research Officer for Habitable.

She digs into the environmental implications of paint components and offers scientific insights on sustainable alternatives. Some of her suggestions are even trending—popular wall treatments such as Limewash and Roman clay are healthier alternatives.

Discover the urgent need to protect children’s developing brains from the harmful effects of plastics and toxic chemicals with this recent report, “Protecting the Developing Brains of Children from the Harmful Effects of Plastics and Toxic Chemicals in Plastics.”

This briefing paper, prepared by experts from Project TENDR, summarizes mounting scientific evidence linking plastic exposure to neurodevelopmental disabilities and cognitive deficits in children. It also provides essential policy recommendations to strengthen the new global treaty on plastics pollution. Download the report or watch the webinar to learn more about how we can address the toxicity and proliferation of plastics and petrochemicals.

The circular economy is a transformative system where materials are continuously repurposed, ensuring nothing becomes waste and nature is regenerated.

This approach involves processes like maintenance, reuse, refurbishment, remanufacture, recycling, and composting to keep products in circulation. By decoupling economic activity from finite resource consumption, the circular economy addresses climate change, biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution. Rooted in the principles of eliminating waste and pollution, circulating materials at their highest value, and regenerating nature, this resilient system benefits businesses, people, and the environment.

Explore the critical role of value engineering (VE) in plumbing systems with this comprehensive report, “Value Engineering in Plumbing Systems.” Discover how effective VE can optimize costs without compromising essential functions, while understanding the potential pitfalls through real-world examples like the costly Baltimore hotel case.

Learn from the insights of industry professionals who emphasize the importance of balancing cost with durability, safety, and sustainability. This report provides essential guidance for architects, engineers, and contractors on making informed decisions to maintain plumbing system integrity and avoid costly mistakes. Download the report today to enhance your approach to VE in plumbing projects.

In this opinion piece, architect Martha Lewis addresses the ecological polycrisis of the twenty-first century and its impact on the architectural sector, emphasizing the urgent need for architects to reassess material choices and construction methodologies to mitigate environmental consequences.

Tests by Consumer Reports found bisphenols and phthalates, chemicals used in plastic, in a wide range of packaged foods, raising concerns due to their potential health effects, including disruptions to the endocrine system and associated health issues.

Health

Health