READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

Phase 2 of this report is the first of its kind plant-by-plant accounting of the production, use, and releases of chlorine and related pollution around the world. It is intended to inform the efforts of building product manufacturers to reduce pollution in their supply chains.

Chlorine is a key feedstock for a wide range of chemicals and consumer products, and the major ingredient of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic. The report includes details aboutthe production technologies used and markets served by 146 chlor-alkali plants (60 in Asia) and which of these plants supply chlorine to 113 PVC plants (52 in Asia). The report answers fundamental questions like:

- Who is producing chlorine?

- Who is producing PVC?

- Where? How much? And with what technologies?

- What products use the chlorine made in each plant?

Key findings include:

- Over half of the world’s chlorine is consumed in the production of PVC. In China, we estimate that 74 percent of chlorine is used to make PVC.

- 94 percent of plants in Asia covered in this report use PFAS-coated membrane technology to generate chlorine.

- In Asia the PVC industry has traded one form of mercury use for another. While use of mercury cell in chlorine production is declining, the use of mercury catalysts in PVC production via the acetylene route is on the rise. 63 percent of PVC plants in Asia use the acetylene route.

- 100 percent of the PVC supply chain depends upon at least one form of toxic technology. These include mercury cells, diaphragms coated with asbestos, or membranes coated with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), used in chlorine production. In PVC production, especially in China, toxic technologies include the use of mercury catalysts.

Supplemental Documents:

The Global Chemicals Outlook II assesses global trends and progress in managing chemicals and waste to achieve sustainable development goals, with a focus on innovative solutions and policy recommendations.

Thank you to Positive Energy’s Building Science podcast for hosting Habitable’s Gina Ciganik, CEO, and Billy Weber, Collective Impact Director, to discuss our resources and work towards healthier building products.

For years, Habitable has been thinking about and consulting with our partners about how to describe the impact of choosing healthier building products. Here’s why this is a complex and challenging issue for the industry:

- Incomplete knowledge of what many building products are made of

- Limited understanding of the health hazards of the thousands of chemicals in commerce today

- Trade-offs when making material choices

These reasons drive the need for full transparency of chemical contents and full assessment of chemical hazards. This can ultimately lead to optimizing products in order to avoid hazardous chemicals.

Toxic chemicals have a huge and complex impact on the health and well-being of people and the environment. Those impacts are spread throughout a product’s life cycle. For example, fenceline communities can be exposed during the manufacturing of products in adjacent facilities, workers can be exposed on the job during the manufacturing and installation processes, and building occupants can be exposed during the product’s use stage. Some individuals suffer multiple exposures because they are affected in all of those instances.

In addition, toxic chemicals can be released when materials are disposed of or recycled. When they incorporate recycled content into new products, manufacturers can include legacy toxicants, inhibiting the circular economy and exposing individuals to hazardous chemicals—even those that have been phased out as intentional content in products.

We know intrinsically that hazardous chemicals have the potential to do harm and that they commonly do so. For champions of this cause, that understanding of the precautionary principle is enough. Others still need to be convinced and often want to quantify the impact of a healthy materials program. How can healthy building champions start to talk about and quantify the impacts of material choices?

Broad Impacts of Toxic Chemicals

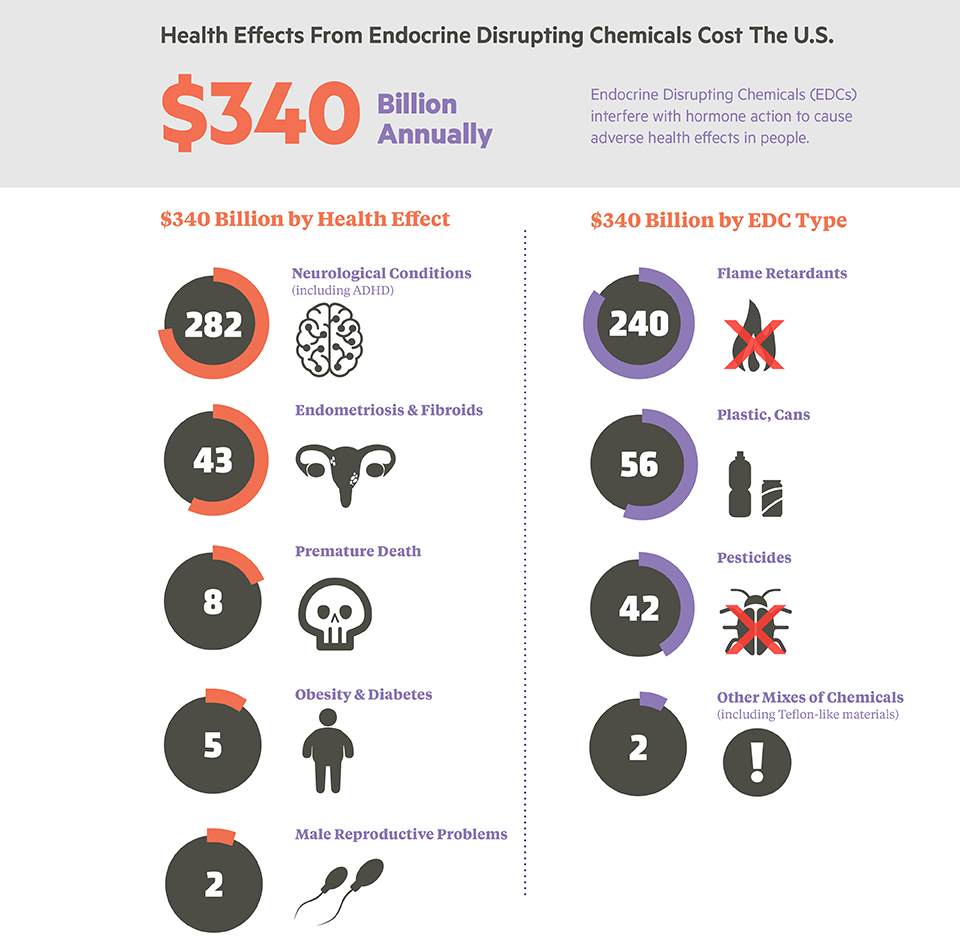

One way researchers quantify the impact of chemicals is to consider the broad economic impacts of chemical exposures. Evidence increasingly shows that toxic chemical exposures may be costing the USA billions of dollars and millions of IQ points. One recent study estimates that certain endocrine-disrupting chemicals cost the United States $340 billion each year. This is a staggerring 2.3% of the US gross domestic product.1 And that is for only a subset of the hazardous chemicals that surround us every day. These numbers provide important context for the larger discussion of toxic chemical use, but cannot easily be tied to daily decisions about specific materials.

Market Scale Impacts

For years, Habitable has been targeting orthophthalates in vinyl flooring as a key chemical and product category combination to be avoided. Orthophthalates can be released from products and deposited in dust which can be inhaled or ingested by residents—particularly young children who crawl on floors and often place their hands in their mouths3. By systematically reducing chemicals of concern in common products, we can all work together to continue to affect this scale of change in the marketplace and keep millions more tons of hazardous chemicals out of buildings.

Impacts on the Project Scale

Context is key for understanding the impact chemical reduction or elimination can have—a pound of one chemical may not have the same level of impact as a pound of another chemical. But, given the right context, this sort of calculation may prove useful as part of a larger story. The following examples provide context for the story of different impacts of different chemicals.

- Small decisions, big impacts: While many manufacturers and retailers have phased out hazardous orthophthalate plasticizers, some vinyl flooring may still contain them. If we consider an example affordable housing project, avoiding orthophthalates in flooring can keep dozens of pounds of these hazardous chemicals out of a single unit (about the equivalent of 10 gallons of milk).4 For a whole building, this equates to several tons of orthophthalates that can be avoided.5 It is easy to see how this impact quickly magnifies in the context of a broader market shift.

- Little things matter: Alkylphenol ethoxylates (APEs) in paints are endocrine-disrupting chemicals make up less than one percent of a typical paint. In this case, by making the choice to avoid APEs, a couple of pounds of these hazardous chemicals are kept out of a single unit (about the equivalent of a quart of milk). This translates to a couple of hundred pounds kept out of an entire building.6 This quantity may seem small compared to the tons avoided in the phthalate example above, but little things matter. Small exposures to chemicals can have big impacts, particularly for developing children.7 And, since our environments can contain many hazardous chemicals, and we aren’t exposed to just a single chemical at a time, these exposures stack up in our bodies.8

- Reducing exposure everywhere: Choosing products without hazardous target chemicals keeps them out of buildings, but can also reduce exposures as these products are manufactured, installed, and disposed of or recycled. Some chemicals may have impacts that occur primarily outside of the residence where they are installed, but these impacts can still be significant. Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), for example, a primary component of vinyl flooring, requires toxic processes for its production and can generate toxic pollution when it is disposed of. Manufacturing of the PVC needed to create the vinyl flooring for one building as described above can release dozens of pounds of hazardous chlorinated emissions, impacting air quality in surrounding communities.9 These fenceline communities are often low-income, and suffer from disproportionate exposure in their homes, through their work, and from local air pollution. If choosing non-vinyl flooring for a single building can help reduce potential exposure to hazardous chlorinated emissions in these fenceline communities, imagine the potential impacts of avoiding vinyl on a larger scale!

In addition to information about target chemicals to avoid, our Informed™ product guidance provides recommendations of alternative types of materials that are typically better from a health hazard perspective and includes steps to work toward the goal of full transparency of product content and full assessment of chemical hazards. This framework can help ensure that toxic chemicals and regrettable substitutions are avoided.

Each decision you make about the materials you use, each step toward using healthier products, can have big impacts within a housing unit, a building, and in the broader environment. Collectively, these individual decisions also influence manufacturers to provide better, more transparent products for us all. Ultimately, this can reduce the hazardous chemicals not just in our buildings but also in our bodies.

SOURCES

- Attina, Teresa M, Russ Hauser, Sheela Sathyanaraya, Patricia A Hunt, Jean-Pierre Bourguignon, John Peterson Myers, Joseph DiGangi, R Thomas Zoeller, and Leonardo Trasande. “Exposure to Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in the USA: A Population-Based Disease Burden and Cost Analysis.” The Lancet 4, no. 12 (December 1, 2016): 996–1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30275-3.

- “Disease Burden & Costs Due to Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals.” NYU Langone Health, July 12, 2019. https://med.nyu.edu/departments-institutes/pediatrics/divisions/environmental-pediatrics/research/policy-initiatives/disease-burden-costs-endocrine-disrupting-chemicals.

- Bi, Chenyang, Juan P. Maestre, LiG Hongwan, GeR Zhang, Raheleh Givehchi, Alireza Mahdavi, Kerry A. Kinney, Jeffery Siegel, Sharon D. Horner, and Ying Xu. “Phthalates and Organophosphates in Settled Dust and HVAC Filter Dust of U.S. Low-Income Homes: Association with Season, Building Characteristics, and Childhood Asthma.” Environment International 121 (December 2018): 916–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.09.013.; Mitro, Susanna D., Robin E. Dodson, Veena Singla, Gary Adamkiewicz, Angelo F. Elmi, Monica K. Tilly, and Ami R. Zota. “Consumer Product Chemicals in Indoor Dust: A Quantitative Meta-Analysis of U.S. Studies.” Environmental Science & Technology 50, no. 19 (October 4, 2016): 10661–72. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b02023.

- According to the USDA, milk typically weighs about 8.6 pounds per gallon. See: “Weights, Measures, and Conversion Factors for Agricultural Commodities and Their Products.” United States Department of Agriculture, June 1992. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/41880/33132_ah697_002.pdf?v=0.

- HBN used the Common Products for Luxury Vinyl Tile and Vinyl Sheet to estimate the amount of plasticizer. We assumed a 100 unit building of 1000 square foot two-bedroom apartments with vinyl flooring throughout the units.

- HBN used the Common Product profiles for Eggshell and Flat Paint to estimate the amount of surfactant and assumed a 100 unit building of 1000 square foot two-bedroom apartments.

- Vandenberg, Laura N., Theo Colborn, Tyrone B. Hayes, Jerrold J. Heindel, David R. Jacobs, Duk-Hee Lee, Toshi Shioda, et al. “Hormones and Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: Low-Dose Effects and Nonmonotonic Dose Responses.” Endocrine Reviews 33, no. 3 (June 1, 2012): 378–455. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2011-1050.

- Impacts can be additive, where health impacts are equal to the sum of the effect of each chemical alone. They can also be synergistic, where the resulting health impacts are greater than the sum of the individual chemicals’ expected impacts.

- HBN used the Common Products for Luxury Vinyl Tile and Vinyl Sheet to estimate the amount of PVC. We assumed a 100 unit building of 1000 square foot two-bedroom apartments with vinyl flooring throughout the units. Emissions are based on the Calvert City, KY Westlake plant examined in HBN’s Chlorine and Building Materials Project. According to EPA’s EJScreen tool, the census blockgroup where this facility is located is primarily low income, with 62% of the population considered low income (putting this census block group in the 88th percentile nationwide in terms of low income population). EJScreen, EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool (Version 2018). Accessed March 18, 2019. https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/.

If we say climate change, what is the first thing that pops into your head? It’s probably not the impact of toxic chemicals on the environment.

Some people can probably name a chemical that contributes to climate change, whether that is carbon dioxide or methane. But what about other chemicals that you are not as familiar with? In the building materials world, these may include fluorinated blowing agents used in some foam insulation. The agents either have high global warming potential (GWP) or use chemicals in their production that have high GWP.1 Another example is the release of the toxic, global warming, and ozone-depleting chemical carbon tetrachloride in the enormous supply chain of vinyl products, otherwise known as poly vinyl chloride (PVC).2 Purveyors of vinyl products, you may unwittingly be contributing to global warming!

Yes, the way in which certain chemicals contribute to climate change is important, but this interplay is not the only consequence of chemicals on our climate. Climate change is also altering how toxic chemicals impact our health and the health of the environment – as the world warms, reducing our exposure to toxic chemicals becomes ever more important.

Five Reasons Why Climate Change and Toxic Chemicals are Connected

- Temperatures affect how chemicals behave – warmer temperatures increase our exposure to toxic chemicals—.3 Higher temperatures can allow certain chemicals to vaporize more easily and enter the air we breathe.4 Warmer temperatures on Earth can also encourage the breakdown of some chemicals into toxic byproducts.5

- Impacts of extreme weather events include concentrated releases of chemicals—catastrophic weather-related events such as hurricanes, fires, etc. can result in the release of toxic chemicals into the air when homes burn, or as factories in the Gulf region are damaged or destroyed.6 These events are becoming more and more frequent and will continue to expose people and the planet to highly concentrated chemical doses.

- Climate change can exacerbate the health impacts of air pollution—volatile organic compounds released by chemical products contribute to the production of smog, leading to poor air quality which can negatively impact the lungs or exacerbate respiratory diseases such as asthma or Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.7 Warmer temperatures amplify these impacts.8 As the largest source of air pollutants slowly transitions from transportation sources to chemical products, and as the earth warms, smart product choices will have even more impact on air quality.9

- Toxic chemicals may hinder the body’s ability to adapt to climate change—in recent years, studies discovered that many toxic chemicals are endocrine disruptors.10 Animal studies have highlighted that endocrine-disrupting chemicals can alter metabolism and hinder animals’ ability to adapt to changing temperatures.11 While these findings were in animals, similar effects occur in humans as well, particularly in communities without access to heating or air conditioning.

- Toxic chemicals increase communities’ vulnerability to climate change effects—toxic chemicals are an environmental justice issue. Ever heard of Cancer Alley? Cancer Alley is a predominantly African American community located in Southern Louisiana right next door to factories pumping out toxic chemicals every day.12 This 100 mile stretch of land is home to 25 percent of the nation’s petrochemical manufacturing and a large portion of its PVC supply chain.13 Aptly named, the cancer rate in this area is higher than the state and national cancer rate.14 Cancer Alley’s location right next to the Gulf Coast also increases its vulnerability to hurricanes and tropical storms. As climate change increases the frequency of extreme weather events, the impacts of toxic chemicals on this community also deepens.

Caring About Toxic Chemicals Can Help Mitigate the Impact of Climate Change—For You!

While most toxic chemicals do not cause climate change, they do affect how climate change might impact you. These impacts compound as more chemicals are produced or utilized.15 In 1970, the U.S. produced 50 million tons of synthetic chemicals.16 In 1995, the number tripled to 150 million tons, and today, that number continues to increase.17

Very few of the tens of thousands of chemicals on the marketplace are fully tested for health hazards, and details on human exposure to these chemicals are limited.18 We are exposed to these chemicals every day, in varying quantities and mixtures. Over a lifetime, the small exposures add up. Predictions of health outcomes from long-term exposure are already fuzzy at best, but add on the component of climate change and the mystery deepens.19 While researchers continue to study climate change and chemicals to answer the questions we have, there are steps that we can take to help mitigate the negative impact of climate change on chemicals.

Habitable’s Small Piece of the Pie — How We’re Keeping Consumers Safe

We cannot remove all chemicals from our lives and many play important roles, but, we can follow the precautionary principle. If there is a less toxic chemical or product available that meets our requirements, we should use it. At Habitable, our work is guided by the precautionary principle—otherwise known as ‘better to be safe than sorry.’ Our chemical and product guidance provides advice on better products.Empowering industry to choose safer chemicals and products helps reduce the burden of toxic chemicals on all people and the planet – especially our most vulnerable populations.

Why We Can and Must Do Better

Between climate change and toxic chemicals, it could be easy to push toxic chemicals to the side as a someday problem and choose to tackle climate change first. But the truth is that the impacts of toxic chemicals are real and happening today and will only get worse in a warming world. These two issues are connected and influence each other’s outcomes. Climate change is having a significant impact on our world, but prioritizing reduction of toxic chemicals can reduce the negative consequences that climate change will have on chemicals, and consequently on us.

SOURCES

- Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) are being phased out as blowing agents in plastic foam insulation due to regulatory action in the United States. Starting in January of 2020, they are no longer allowed in most spray foam insulation. Extruded polystyrene (XPS) insulation manufacturers have until January of 2021 to phase out HFCs. The commonly used HFC in XPS, HFC-134a has a global warming potential 1,430 times that of carbon dioxide. A common replacement blowing agent for HFCs is a hydrofluoroolefin (HFO). While the HFO itself has a low GWP, it still uses high GWP chemicals in its production and may release these chemicals when it is made. See “Making Affordable Multifamily Housing More Energy Efficient: A Guide to Healthier Upgrade Materials,” Healthy Building Network, September 2018, https://informed.habitablefuture.org/resources/research/11-making-affordable-multifamily-housing-more-energy-efficient-a-guide-to-healthier-upgrade-materials.; “Substitutes in Polystyrene: Extruded Boardstock and Billet.” United States Environmental Protection Agency: Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP). Accessed Sept 16, 2019. https://www.epa.gov/snap/substitutes-polystyrene-extruded-boardstock-and-billet.; “Substitutes in Rigid Polyurethane: Spray.” United States Environmental Protection Agency: Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP). Accessed Sept 16, 2019. https://www.epa.gov/snap/substitutes-rigid-polyurethane-spray.

- Vallette, Jim. “Chlorine and Building Materials: A Global Inventory of Production Technologies, Markets, and Pollution – Phase 1: Africa, The Americas, and Europe.” Healthy Building Network, July 2018. https://habitablefuture.org/resources/chlorine-building-materials-project-phase-1-africa-the-americas-and-europe/.

- Pamela D. Noyes et al., “The Toxicology of Climate Change: Environmental Contaminants in a Warming World,” Environment International 35, no. 6 (August 1, 2009): 971–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2009.02.006.

- Noyes et al.

- Pamela D. Noyes and Sean C. Lema, “Forecasting the Impacts of Chemical Pollution and Climate Change Interactions on the Health of Wildlife,” Current Zoology 61, no. 4 (August 1, 2015): 669–89, https://doi.org/10.1093/czoolo/61.4.669.

- Caroline C. Ummenhofer and Gerald A. Meehl, “Extreme Weather and Climate Events with Ecological Relevance: A Review,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 372, no. 1723 (June 19, 2017): 20160135, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0135.

- C. M. Zigler, C. Choirat, and F. Dominici, “Impact of National Ambient Air Quality Standards Nonattainment Designations on Particulate Pollution and Health.,” Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.) 29, no. 2 (March 2018): 165–74, https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000777.

- “Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs).” Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.pca.state.mn.us/air/volatile-organic-compounds-vocs.

- Brian C. McDonald et al., “Volatile Chemical Products Emerging as Largest Petrochemical Source of Urban Organic Emissions,” Science 359, no. 6377 (February 16, 2018): 760–64, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaq0524.

- Research Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, and Institute of Medicine, The Challenge: Chemicals in Today’s Society (National Academies Press (US), 2014), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK268889/.

- Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Practice, and Medicine.

- Wesley James, Chunrong Jia, and Satish Kedia, “Uneven Magnitude of Disparities in Cancer Risks from Air Toxics,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 9, no. 12 (December 2012): 4365–85, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9124365.

- James, Jia, and Kedia.; Vallette.

- James, Jia, and Kedia.

- Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Practice, and Medicine.

- Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Practice, and Medicine

- Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Practice, and Medicine.

- Pamela D. Noyes and Sean C. Lema, “Forecasting the Impacts of Chemical Pollution and Climate Change Interactions on the Health of Wildlife,” Current Zoology 61, no. 4 (August 1, 2015): 669–89, https://doi.org/10.1093/czoolo/61.4.669

- Noyes and Lema.

Two important initiatives are gaining momentum in the green building movement. One seeks to reduce the embodied carbon of building products. The other seeks to increase inclusion, diversity and equity in the green building industry.

It is critical that these efforts align their goals lest, once again, the latest definition and marketing of “green” building products overlooks and overrides the interests of the front line communities most impacted by both climate change and toxic pollution.

The Carbon Leadership Forum describes embodied carbon as “the sum impact of all the greenhouse gas emissions attributed to the materials throughout their life cycle (extracting from the ground, manufacturing, construction, maintenance and end of life/disposal).2 In a widely praised book, The New Carbon Architecture3, Bruce King explains clearly why reducing carbon inputs to building materials immediately—present day carbon releases—is more effective at meeting urgent carbon reduction goals than the gains of even a Net Zero building, which are realized over decades. This approach is embraced by the Materials Carbon Action Network, a growing association of manufacturers and others, which states as its aim “prioritization of embodied carbon in building materials.”(emphasis added).4

Climate action priorities are framed differently by groups at the forefront of movements for climate justice and equity in the green building movement. Mary Robinson, past President of Ireland, UN High Commissioner on Human Rights and UN Special Envoy on Climate Change, says climate justice “insists on a shift from a discourse on greenhouse gases and melting ice caps into a civil rights movement with the people and communities most vulnerable to climate impacts at its heart.” 5 The Equitable and Just National Climate Platform6, adopted by a broad cross section of environmental justice groups and national organizations including Center for American Progress, League of Conservation Voters, Natural Resources Defense Council, and Sierra Club, calls for “prioritizing climate solutions and other policies that also reduce pollution in these legacy communities at the scale needed to significantly improve their public health and quality of life.” The NAACP’s Centering Equity In The Sustainable Building Sector (CESBS)7 initiative advocates “action on shutting down coal plants and other toxic facilities at the local level, as well as building of new toxic facilities, with advocacy to strengthen development, monitoring, and enforcement of regulations at federal, state, and local levels. Also includes a focus on corporate responsibility and accountability.”8

The embodied carbon and climate justice initiatives are aligned when carbon reductions in building products are achieved through industrial process changes that reduce the use of fossil fuels and other petrochemicals. But rarely, if ever, can building products be manufactured with no carbon footprint, i.e. without fossil fuel inputs. These initiatives may not be aligned when manufacturers promote “carbon neutral” or “carbon negative” products that rely on carbon trading or offsets, the practice of supporting carbon reduction elsewhere (by planting trees or investing in renewable energy) to offset fossil fuel and petrochemical inputs at the factory. According to the Equitable and Just National Climate Platform: “ . . . these policies do not guarantee emissions reduction in EJ communities and can even allow increased emissions in communities that are already disproportionately burdened with pollution and substandard infrastructure.” They may also allow increased toxic pollution, if a manufacturer chooses to invest in carbon offsets, for example, rather than invest in process changes that reduce toxic chemical use or emissions. As a result, disproportionate impacts, often correlated with race, can be perpetuated.

Vinyl provides one example of such inequity. Vinyl’s carbon footprint includes carbon tetrachloride, a chemical released during chlorine production that is simultaneously highly toxic, ozone depleting, and a global warming gas 1,400 times more potent than CO2. Offsetting these releases with tree planting or renewable energy purchases does nothing for the toxic fallout, from carbon tetrachloride, fossil fuels and other petrochemicals, on the communities adjacent to those manufacturing facilities.

Experts agree that the most embodied carbon reductions by far are to be had in addressing steel and concrete in buildings. Beyond that, experts disagree about the strength of the data available to track carbon reductions and compare products in a meaningful, objective way, and warn of diminishing returns relative to the investment needed to track carbon in every product. These may prove to be worth pursuing, but not at the expense of meaningful improvements to conditions in fenceline communities.

Habitable believes that these approaches can be reconciled and aligned through dialogue that includes the communities most impacted by the petrochemical infrastructure that is driving climate change. Our chemical hazard database, Pharos, and our collaboration with ChemFORWARD provide manufacturers with the ability to reduce their product’s carbon and toxic footprints.

We can in good faith pursue reductions in embedded carbon and toxic chemical use, climate and environmental justice and to define climate positive building products accordingly. Prioritizing selection of products simply upon claims of carbon neutrality, however, is not yet warranted.

SOURCES

- U.S. Green Building Council, “Resources | U.S. Green Building Council,” LEED, accessed November 14, 2019, http://www.usgbc.org/resources/social-equity-built-environment.

- Carbon Leadership Forum, “Why Embodied Carbon?,” Carbon Leadership Forum (blog), accessed November 14, 2019, http://carbonleadershipforum.org/about/why-embodied-carbon/.]

- Ecological Building Network, “The New Carbon Architecture,” EBNet, accessed November 14, 2019, https://www.ecobuildnetwork.org/projects/new-carbon-architecture.

- Interface, “MaterialsCAN,” accessed November 14, 2019, https://www.interface.com/US/en-US/campaign/transparency/materialsCAN-en_US.

- Martin, “Climate Justice,” United Nations Sustainable Development (blog), May 31, 2019, https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/05/climate-justice/.

- Equitable and Just, “A Just Climate,” accessed November 14, 2019, https://ajustclimate.org.

- NAACP, “NAACP | Centering Equity in the Sustainable Building Sector,” NAACP, accessed November 14, 2019, https://www.naacp.org/climate-justice-resources/centering-equity-sustainable-building-sector/.

- NAACP, “NAACP | NAACP Environmental and Climate Justice Program,” NAACP, accessed November 14, 2019, https://www.naacp.org/environmental-climate-justice-about/.

Home Depot, the world’s largest home improvement retailer, announced Sept. 17 that it will phase out the sale of all carpets and rugs containing PFAS chemicals, expanding the reach of its Chemical Strategy adopted in 2017.

The company said it will stop purchasing for distribution in the U.S., Canada and online any carpets or rugs containing PFAS chemicals by the end of 2019. The new policy has important implications beyond reducing the use of these chemicals, which are associated with serious health harm and last virtually forever in the environment.

Environmental justice & equity: As with the 12 chemicals banned under its original 2017 Chemicals Strategy, this policy makes important strides toward equity in the green building movement. Because it impacts products at all price points, not just premium products and not just those that qualify for the retailer’s Eco-Options program, the policy ensures that all contractors and do-it-yourself customers get healthier products regardless of the brand purchased, and regardless of whether or not the product has been certified “green.” This makes it easier to implement recommendations such as those Habitable provides through our Informed™ approach.

Market Influence

A similar policy change led by the retailer in 2015, banning phthalates from all vinyl flooring it sells, was quickly adopted by all other major retailers such as Lowes, Menards, and Lumber Liquidators. Similarly, when Lowes led the industry in banning the sale of deadly paint strippers in May, 2018, its major competitors followed suit within months

Class approach to chemicals

PFAS refers to a class of nearly 15,000 that repel liquids and resist sticking, including well-known brands such as Teflon, Gore-Tex, Stainmaster and Scotchgard. Many brands have stopped using the most well studied, “long-chain” compounds in this class, but continue to use less studied “short-chain” compounds, causing confusion for consumers. Independent scientists agree that a commitment to avoiding all PFAS is the right approach for consumers and the overall environment.

Widespread PFAS Contamination of the Environment Is a Growing Concern. The Environmental Working Group (EWG) has identified over 700 sites where PFAS were detected and cited federal data suggesting that up to 110 million Americans may have PFAS in their drinking water.1 HBN’s analysis of chlorine and PVC production documented unexpectedly high use of PFAS as an alternative to mercury- and asbestos-based chlorine manufacturing technology, raising new concerns about the role of chlorine-based products and the growing concern over global PFAS exposures. The chemical industry argues that only a few of these compounds have been found unsafe, and all others should be presumed innocent until proven guilty. In 2019, 3M company launched a major public relations blitz2 to this effect, including a “PFAS Facts” website advocating that “Each PFAS compound needs to be evaluated based upon its own properties,”3 a process that would take federal regulators, at best, many decades to complete. EWG published a thorough refutation of 3M’s claims,4 and more than 250 independent scientists5 have called upon companies and regulators to stop producing and using PFAS except in the most essential applications. The Home Depot’s new carpet and rug policy, which we hope will soon be extended to other products including spray-on upholstery protection, such as 3M’s Scotchgard, follows this recommended class approach.

The Home Depot’s new policy commitment comes just two months before the release of the 2019 “Who’s Minding the Store?” Retailer Report Card, from the Mind the Store campaign, a nationwide coalition that challenges retailers to eliminate toxic chemicals and substitute safer alternatives. HBN is a coalition member and advised The Home Depot on its 2017 Chemical Strategy. The annual Report Card benchmarks retailers on their safer chemicals policies and implementation programs. The Home Depot earned a B- on the scorecard.

To learn more about PFAS and how to avoid them, watch the documentary The Devil You Know, available on all streaming services, and check out the new PFAS Central website, a project of our partners at the Green Science Policy Institute.

SOURCES

- https://www.ewg.org/research/report-110-million-americans-could-have-pfas-contaminated-drinking-water

- https://news.3m.com/press-release/company-english/3m-announces-pfas-initiatives-actions

- https://pfasfacts.com

- https://www.ewg.org/news-and-analysis/2019/09/science-pfas-rebuttal-3m-s-claims

- https://greensciencepolicy.org/madrid-statement/

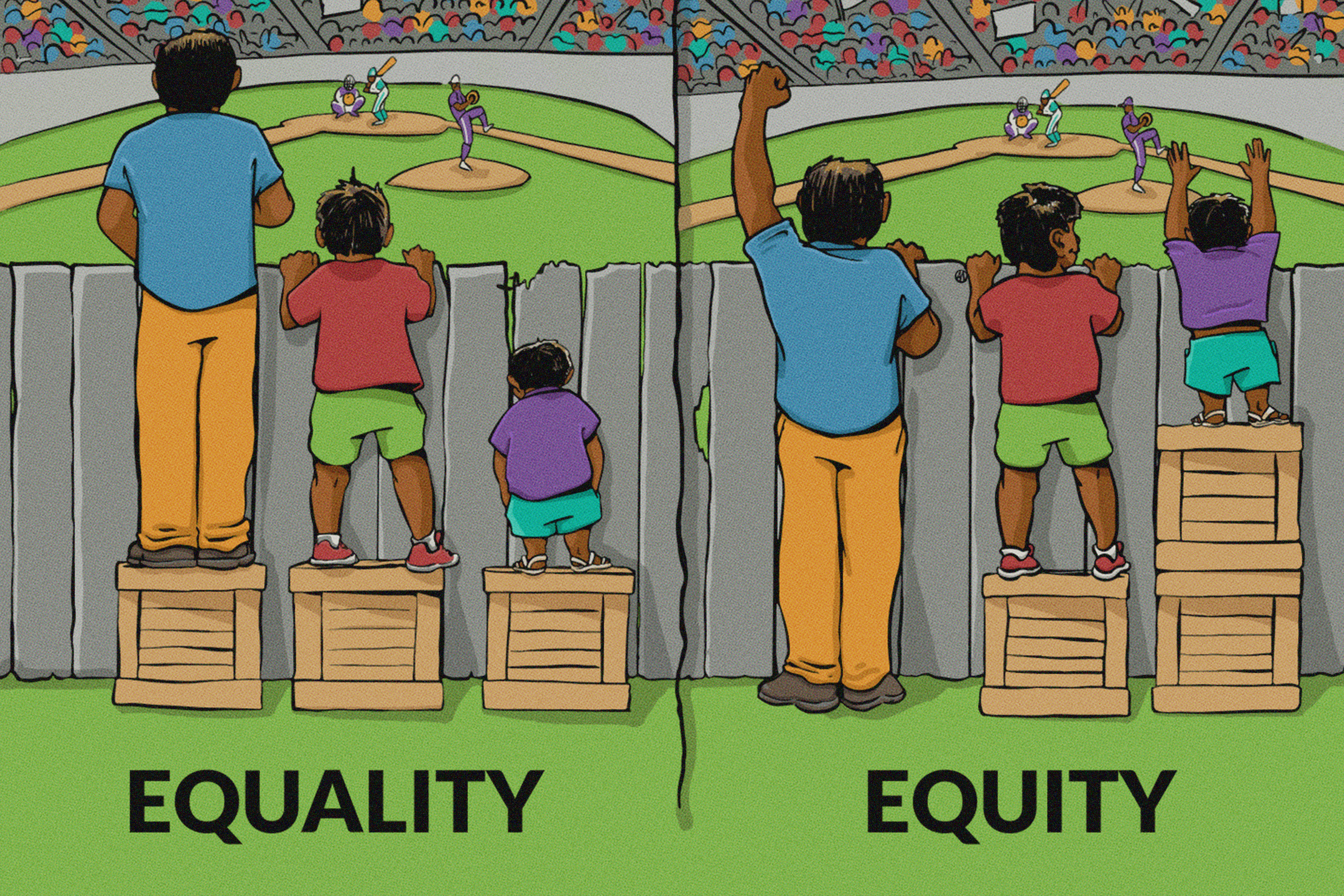

A whole lot of meaning is packaged in the word equity—a term Webster’s defines as “fairness or justice in the way people are treated.” However, the easiest way to understand equity is often through pictures, like the one below.

While this photo considers height as an inequity, in real life, income, access to food and health care are often at the heart of equity discussions. Surprisingly, a critical topic often overlooked in the equity discussion is where we spent 90 percent of our lives—in buildings.1

Oregon Metro, otherwise known simply as Metro, released a report discussing toxics reduction and equity. Its section on building materials connects building materials and equity, calling attention to the need to reduce community exposure to toxic building materials in an equitable manner. Building materials seem harmless and inert in our homes, offices, schools, or cafes. But in 1991, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) characterized indoor air pollution as “one of the greatest threats to public health of all environmental problems”.2

A large proportion of indoor air pollution stems from building materials.3 In particular, asthmagens are of highest concern and contribute to indoor air pollution through the release of chemicals from the surface of building finishes.4 For example, carpet, furniture and wall decor release chemicals through degradation or abrasion.5 The chemicals end up in dust in our homes and can enter our bodies through the lungs, skin or mouth.6 Volatile organic compounds emitted from paints are also of concern.7 In fact, a study of children in Australia showed a strong association among indoor home exposure to VOCs and increased risk of asthma.8 Over 70 percent of building material asthmagens identified by Healthy Building Network (HBN) researchers are not covered by leading indoor air quality testing standards.9 These hazardous wastes and products used in building materials disproportionately affect historically marginalized communities of color, children and low-income families.10

Equity in housing is especially important for many families with low incomes who live in multifamily housing.11 Multifamily housing often poses challenges to achieving better air quality as pollutants easily travel between units due to inadequate ventilation. Residents are usually unable to improve building infrastructure themselves.12

Incorporating building materials into the equity discussion is only part of the solution. Product testing for chemicals of concern, biomonitoring, community health impact research, chemicals research, advocacy and education all stand to make a larger collective impact.13

For funders looking to increase diversity and equity initiatives in their grant making, the building industry provides a blooming landscape to foster substantial impact within communities. Here are some key questions to consider when funding proposals:

- What is the specific toxics reduction action?

- Are there particular populations or communities impacted more than the general population by the chemical/product/system in question?

- Does the action consider and address the structural barriers and existing resources available to a population?

- Does the recommendation ameliorate the disparity or gap in accessing resources for a marginalized community?

So often, sustainability standards and initiatives are cost prohibitive, developed for those with the most access and resources, in hopes that “someday” the solutions will trickle-down. In the meantime, children and the populations with the lowest income continue to bear the burden of toxic exposures and preventable health consequences. Habitable’s Informed™ healthy product guidance is changing that old, unsuccessful paradigm. Our resources will result in healthier products for everyone, and amplify the prospect for a healthier planet.

Visit informed.habitablefuture.org to join the movement towards a healthy future for all.

SOURCES

- Cuneo, Monica et. al. Toxics Reduction and Equity: Informing actions to reduce community risks from chemicals in products. Oregonmetro.gov, 2019. August 14, 2019. https://www.oregonmetro.gov/toxics-reduction-and-equity-study

- Ibid.

- Environmental Protection Agency. “Fundamentals of Indoor Air Quality in Buildings.” Indoor Air Quality, 1 Aug. 2018, www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/fundamentals-indoor-air-quality-buildings#Factors.

- Lott, Sarah, and Jim Vallette. Full Disclosure Required: A Strategy to Prevent Asthma Through Building Product Selection. Healthy Building Network, December 2013. August 14, 2019. https://habitablefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/93-full-disclosure-required-a-strategy-to-prevent-asthma-through-building-product-selection.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Singla, Veena. Toxic Dust: The Dangerous Chemical Brew in Every Home. Natural Resources Defense Council, September 13, 2016. August 20, 2019. https://www.nrdc.org/experts/veena-singla/toxic-dust-dangerous-chemical-brew-every-home

- Lott, Sarah, and Jim Vallette. Full Disclosure Required: A Strategy to Prevent Asthma Through Building Product Selection. Healthy Building Network, December 2013. August 14, 2019. https://habitablefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/93-full-disclosure-required-a-strategy-to-prevent-asthma-through-building-product-selection.pdf.

- Rumchev, K, et al. Association of Domestic Exposure to Volatile Organic Compounds with Asthma in Young Children. Thorax, BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, 1 Sep. 2004. August 14, 2019. http://thorax.bmj.com/content/59/9/746.

- Lott, Sarah, and Jim Vallette. Full Disclosure Required: A Strategy to Prevent Asthma Through Building Product Selection. Healthy Building Network, December 2013. August 14, 2019. https://habitablefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/93-full-disclosure-required-a-strategy-to-prevent-asthma-through-building-product-selection.pdf.

- Cuneo, Monica et. al. Toxics Reduction and Equity: Informing actions to reduce community risks from chemicals in products. Oregonmetro.gov, 2019. August 14, 2019. https://www.oregonmetro.gov/toxics-reduction-and-equity-study

- Ibid.

- Hayes, Vicky et al. Evaluating Ventilation in Multifamily Buildings. Home Energy Magazine, August 1994. August 14, 2019. www.homeenergy.org/show/article/nav/ventilation/id/1059.

- Cuneo, Monica et. al. Toxics Reduction and Equity: Informing actions to reduce community risks from chemicals in products. Oregonmetro.gov, 2019. August 14, 2019. https://www.oregonmetro.gov/toxics-reduction-and-equity-study

You may know the phrase, “you are what you eat.” There is a parallel concept when it comes to hazardous chemicals—you are what surrounds you!

Every day we come in contact with a large number of chemical products. Think of the last time you walked through a space being remodeled, or sat in a new car and thought “what’s that smell?” Your body notices that smell because a chemical or substance is interacting with the smell receptors in your nose. The same characteristics that allow it to interact with your nose could make those chemicals affect the body in other ways too—sometimes causing harm. The more invisible moments occur when sleeping on your mattress filled with flame retardants or using your personal care products while getting ready for work. Perhaps you work in a factory, as a contractor installing products, or some other job requiring direct contact with a variety of chemicals. The list (both visible and invisible) goes on and on. While a one-time exposure might not lead to health effects, a life-time of exposure and buildup to these chemicals can. More and more scientific evidence links these chemical exposures to diseases like cancer and diabetes, as well as developmental delays, reproductive health issues, and Autism Spectrum Disorder1.

There are three main exposure pathways: 1) inhalation – breathing in contaminated air, 2) ingestion – the inadvertent passing of dust or other chemical residues from hands to mouth, and 3) because our skin is like a sponge – absorption through dermal contact. According to the Environmental Working Group (EWG), babies still in the womb are exposed to more than 200 chemicals that pass from their mother through the umbilical cord2. This should make you wonder—what are the chemicals I may not realize are entering my body? There is a term used to describe the load of chemicals in the human body—body burden.

There’s what in my body?!

We sat down with Teresa McGrath, Healthy Building Network’s (HBN) Chief Research Officer earlier this year to talk about urine, specifically hers. Earlier this year, Teresa participated in a study on chemical body burden led by Silent Spring Institute. Teresa is an avid runner who’s completed marathons and loves snacking on fresh vegetables from her local farmers market. She is one of the healthiest and most health conscious individuals on our team and we were very interested in learning her results.

The study, titled Detox Me Now, included approximately 350 participants. Teresa submitted her urinary sample for testing 15 chemicals, including3:

- Chlorinated phenols

- Bisphenols

- Alkylphenol ethoxylates (found in paints)

- UV filters

- Parabens (commonly used in makeup products as a preservative)

- Antimicrobials

Teresa’s Results

Her study results detected seven of the 15 chemicals tested in her urine sample. There are a couple of basic rules to follow when it comes to interpreting biomonitoring results. The first is that a higher number is not always a reason for concern4. And the second is that from a hazard perspective, not all chemicals are the same5. Each chemical possesses its own set of health effects at different dosages and routes of exposure6.

Regrettable Substitutions

During our conversation, Teresa McGrath offered a particularly interesting study finding—her differing bisphenol results particularly when compared to the study median and the US median.

This study tested for two bisphenols, bisphenol-A (BPA) and bisphenol-S (BPS). If BPA sounds familiar, that is probably because this is the much-talked about ingredient commonly used in polycarbonate plastic bottles, lining for food and beverage cans and thermal paper receipts. It can cause endocrine disruption.7,8 BPS is a common replacement for BPA in many thermal applications including paper receipts and plastics and has similar health concerns as BPA9. Teresa’s results for BPA were lower than the median for the Silent Spring Detox Me Now study participants AND lower than the US median10. However, her BPS levels were greater than her BPA levels, greater than the median for the Silent Spring Detox Me Now study participants AND greater than the US median11. This is illustrated in the following graphic from her study report.

The report offers two possible explanations:

- Teresa successfully avoids BPA by choosing products that are BPA-free and unwittingly preferring products that use BPS, the common BPA alternative.

- The timing of the studies coincided with an industry-wide shift from BPA to other bisphenols, including BPS. The US median data (NHANES) was collected between 2013 and 2014, while the Detox Me Action Kit test samples are dated 2016 to 2018.

By simply purchasing BPA-free products, one can reduce exposure to BPA. However, industries continue to choose “regrettable substitutions” or replacing one chemical with another similar chemical and/or a chemical with unknown health effects. Much of our work focuses on helping industries avoid regrettable substitutions.

Here’s how you can decrease your exposure to toxic chemicals.

Wrapping up our conversation with Teresa, we briefly discussed the overall study implications and additional survey results. Compared to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted by the Centers for Disease Control, participants of this study possessed lower chemical burdens than most people in the United States. One explanation for this may be attributed to 43 percent of participants self-reporting that they avoid products with parabens, BPA, triclosan, and fragrance, and an additional 40 percent reported avoiding two or three of those chemicals.

So, how can you reduce your exposure? Silent Spring offers some ideas, including:

- Asking your favorite brands and stores to choose safer chemicals

- Avoiding personal care products and cosmetics that list parabens as ingredients

- Learning which personal care and cosmetics companies avoid harmful chemicals

You can also download their Detox Me Now App for more tips.

Biomonitoring studies similar to Silent Spring’s are springing up in recent years, as have articles about their results, such as this story in the Guardian. For only a few hundred dollars, consumers can know the exact chemical composition of their bodies. For those who find sample submission undesirable, HBN has added a new feature in our Pharos platform that provides links to biomonitoring databases with information on chemicals identified in the bodies of individuals from different regional communities. The results continually shed light on the need for greater industrial transparency and a transition to safer products.

This is one more example of why HBN passionately paves the way to safer products, offering recommended alternatives from expert chemical analysis and by fostering collaborative industry partnerships.

SOURCES

- Kim et al., “Exposure to pesticides and the associated human health effects.” Science of the Total Environment 575, (2017). 525-535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.009

- Environmental Working Group, “ Body Burden: The Pollution in Newborns.” Environmental Working Group, last modified July 14, 2005, https://www.ewg.org/research/body-burden-pollution-newborns.

- Fransway et al.. “Parabens.” Dermatitis 30, 1 (2019). 3-31. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000429

- Casarett, Louis J., John Doull, and Curtis D. Klaassen. 2001. Casarett and Doull’s toxicology: the basic science of poisons. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Pub. Division.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- National Toxicology Program, “Bisphenol A (BPA),” National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, last modified May 23, 2019, https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/sya-bpa/index.cfm.

- Silent Spring Institute, “Our Science”, Silent Spring Institute, accessed September 17, 2019, https://libanswers.snhu.edu/faq/48009.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. The “US median” results in this article refer to the NHANES study. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a program established in the 1960s run by the Centers for Disease Control that tracks the health of adults and children in the United States. NHANES tested surveyed individuals for many of the Detox Me Now Action Kit chemicals. The most recent NHANES data, from 2013-2014, were used as a nationally representative estimate of exposure in the United States.

- Ibid.

Current climate action plans are bold, they are necessary, they feel impossible, and they are coming into the consciousness of all concerned (and unconcerned), decades after the early reports should have been taken seriously.

At this point, there is an urgency because people are now experiencing the effects of a warming planet:storms, fires, rising tides, health impacts from warmer temperatures, and more.

To date, climate plans have focused on strategies related to renewable and clean energy, greater efficiency, emissions reduction, etc., especially as it relates to building operations and transportation. However, that is only one side of the (enormous) coin, and it misses key opportunities on the opposite side. It is akin to making the decision to improve your health by incorporating an exercise plan, but continuing a diet of nutritionally deficient and unhealthy foods. You will only get so far, and your dedication to exercise will be undercut by your fast food burgers and supersized fries.

The other side of the coin? If building and transportation energy and emissions reduction is “heads,” what could be so immense that it fills the flipside? The “tails” of that coin is the vast quantities of products being produced, its emissions and pollution, and the need for toxic chemical mitigation. The missing piece in effective climate mitigation and improved global health is a toxic-free, recyclable product cycle (low-waste and closed-loop).

The Link Between Emissions, Circular Economy, and Chemicals

Climate plans must include Circular Economy strategies, and a circular economy is possible only if safe chemistries are used as inputs to products.1 The Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s (EMF) September 2019 report: Completing the Picture: How the Circular Economy Tackles Climate Change makes the case that we must address the product cycle as a core part of climate action plans.2 According to the report, “to date, efforts to tackle the [climate] crisis have focused on a transition to renewable energy, complemented by energy efficiency. Though crucial and wholly consistent with a circular economy, these measures can only address 55% of emissions. The remaining 45% comes from producing the cars, clothes, food, and other products we use every day.”

There is more than just emissions that makes the product cycle a critical component of an effective climate strategy. At Habitable, our research shows that there is a related and similar urgency in addressing severe health crises, impacting marginalized communities the hardest, but also now affecting a larger population of people. Our plans—starting with transparency (requesting manufacturers provide the public with a complete list of product ingredients); full testing of all chemicals for human and environmental health impacts; and innovation to new, “green” (safer) chemicals—are bold, necessary and they also feel impossible.

The EMF Completing the Picture report makes the case that we must fundamentally change how our products are made. A key recommendation in reducing emissions is to “design out waste and pollution.” To be even more precise, designing the toxics out of our products is key to eliminating waste and creating the safe and circular economy that is the cornerstone of any climate solution, an inextricable element in human and environmental health.

A companion report by Google, in partnership with EMF, The Role of Safe Chemistry and Healthy Materials in Unlocking the Circular Economy, emphasizes that toxic chemical mitigation is a precursor to a circular economy. It suggests that “the short- and long-term impacts of these new chemical substances has lagged behind the drive to create new molecules and materials. We can see the consequences around us, including ‘sick building syndrome,’ flame retardants accumulating in human breast milk and being passed along to newborns, or entire city populations toxified from local environmental exposures and contaminated drinking water.” The authors of the report put out a challenge to the world’s chemists and material scientists to not only develop molecules and materials that achieve a performance or aesthetic outcome, but also to ensure that these substances are safe for people and the environment, can be cycled and used to create future products, and retain economic value throughout its lifecycle. Safer chemistry is the key to unlock a circular economy.

The health impacts related to our petrochemical and hazardous chemical-dependent product economy are real, but are often unseen or unrecognized. Globally declining sperm counts and reproductive disorders are linked to chemicals in our plastics,3 and a growing library of peer-reviewed studies link today’s epidemic health issues—cancer, diabetes, obesity, asthma and autism—to endocrine-disrupting and neurotoxic chemicals.4 These data often take a back seat to the climate crisis in our headlines, but they too are growing worse and in need of bold action.

“Better Living Through Chemistry” vs Better Chemistry for Healthier Living

DuPont (and other chemical companies) did not get it right with the blanket phrase, “Better Living Through Chemistry.”

Has there been some great progress and benefits from innovative products that use new chemistries and materials?—yes, of course. That said, a significant lack of understanding of the toxicological effects on humans and the environment have come at great cost. We are finding that the tradeoffs are severe—though today, like the early science on climate change, most people are unaware of this silent epidemic, and tend to accept the rise in cancer, autism, fertility problems, and developmental issues in children, as only an unfortunate part of life—they or their loved ones just pulled a short straw, bad luck.

In 1970, the U.S. produced 50 million tons of synthetic chemicals.5 In 1995, the number tripled to 150 million tons, and today, that number continues to increase.6 Very few of the tens of thousands of chemicals in the marketplace are fully tested for health hazards, and details on human exposure to these chemicals is limited.7 We are exposed to these chemicals every day, in varying quantities and combinations. Over a lifetime, the small exposures add up. Science-based predictions of health outcomes from long-term exposure continue to emerge,8 but add on the component of a warming climate and a new layer of concern is revealing itself.9

Both/And Solution

The best climate plans are holistic. They recognize and include strategies from both the clean and renewable energy effort and safe and circular product cycle. The threats and impacts of climate change and toxic chemicals are synergistic, as are the solutions. They must be tethered in order to be effective. In fact, ignoring the chemical/material side of the coin will undermine progress on climate and energy solutions.

We know better, and we can do better.

As energy efficiency and renewable energy gains reduce the carbon footprint of the transportation and building operations sectors, addressing product production assumes an even greater importance. Successfully addressing climate change requires a revolutionary change in how we design and manufacture materials, towards a circular, closed-loop economy. But materials cannot flow effectively in a closed-loop if they are contaminated with toxic chemicals. Safe first, and then circular is possible.

The urgency to mitigate toxics must be on par with the urgency for clean and renewable energy – they are two sides of the same coin. Failing to recognize this, and create holistic, compatible solutions, will undermine our goals to manage climate change and improve global health.

SOURCES

- “What Is a Circular Economy? | Ellen MacArthur Foundation,” accessed November 25, 2019, https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/concept.

- “Circular Economy Reports & Publications From The Ellen MacArthur Foundation,” accessed November 25, 2019, https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications.

- Teresa Carr, “Sperm Counts Are on the Decline – Could Plastics Be to Blame?,” The Guardian, May 24, 2019, sec. US news, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/may/24/toxic-america-sperm-counts-plastics-research.

- Naoko OHTANI et al., “Adverse Effects of Maternal Exposure to Bisphenol F on the Anxiety- and Depression-like Behavior of Offspring,” The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 79, no. 2 (February 2017): 432–39, https://doi.org/10.1292/jvms.16-0502.

- Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Practice, and Medicine.

- Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Practice, and Medicine.

Pollution

Pollution Health

Health Climate Change

Climate Change Equity

Equity