READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

Scientists are investigating how exposure to environmental stressors during pregnancy affects the health of both fetuses and pregnant individuals, highlighting the need for further research to protect the almost 130 million people worldwide who give birth annually.

A study by environmental health experts at New York University suggests that phthalates, chemicals commonly found in plastic food containers and cosmetic products, may have contributed to approximately 10 percent of preterm births in the United States in 2018.

For over three decades, CEHN has been a leading advocate for evidence-based child-protective policy, preventive research, and education on children’s environmental health, collaborating with diverse stakeholders to promote a healthier future for children.

Toxic-Free Future is a leading advocate for environmental health, leveraging science, education, and activism to promote strong laws and corporate responsibility that safeguard the health of individuals and the planet.

Learn about the United Nations’ General Comment No. 26, which provides guidance on implementing the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child regarding children’s rights and the environment, focusing on the impact of toxic substances.

Overwhelming evidence suggests our health and well-being are significantly impacted by the conditions in the environment where we are born, live, learn, work, and play, with some suggesting that our zip codes are better predictors of health than our genetic code.

Also referred to as social determinants of health , these conditions range from access to and quality of education, transport, and health care services to housing conditions and the toxics and pollutants we are exposed to in the neighborhoods we live in.

While definitions may vary around what these conditions are and which should be prioritized, there is general consensus that:

- These conditions exist because of decision-making processes, policies, structures, and practices designed and implemented by humans;

- These conditions create inequities in health, disproportionately impacting low-income families, families living with incomes below the federal poverty level, and people of color, and;

- Cross-sector collaboration is needed to deliver the highest standards of health for all, with special attention given to the needs of those who are at greatest risk.

In alignment with efforts tackling the root causes of health inequities, Healthy Building Network (HBN) entered into a partnership with United Renters for Justice (IX), a nonprofit working to transform the Minneapolis housing system, to reduce tenant exposures to toxic chemicals used in building products. Funded through an Environmental Assistance grant by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA), this collaborative project prioritized toxic exposure reduction in areas designated to be of environmental justice (EJ) concern by the MPCA. EJ concern areas include tribal land and census tracts with higher concentrations of low-income residents and people of color – communities that are disproportionately impacted by toxic chemical exposures and other forms of pollution.

This collaboration provided the unique opportunity to embrace the perspective of tenants in the co-creation of resources to help them make informed decisions about the products used in their housing units and common areas. Specifically, this meant designing resources that would leverage IX’s organization and mobilization skills as well as the structure of a recently established tenant cooperative, “A Sky Without Limits.” Also, it meant increasing information accessibility, for example, through the use of non-technical language and making the resources available in both English and Spanish.

Tenant organizations and other stakeholders can access HBN’s healthier building product guidance at informed.habitablefuture.org and by watching this 10-minute seminar video:

Watch the Seminar (English)

Ver el Seminario (Español)

This high-level, 10-minute recording can be used to educate the general public (e.g., tenant meetings) about the importance of avoiding toxic products. It begins by breaking down myths and misconceptions around the perceived hazards and safety of natural and synthetic chemicals and discusses how toxic products impact individuals and families, especially children, along the lifecycle of products.

By empowering the people most affected by toxic chemical exposures to advocate for and create change in their living conditions, this project creates avenues for creating a safer environment for all. Anyone who influences product purchasing decisions – including manufacturers, building owners, managers, developers, architects, investors, policy makers, and consumers – has the power and responsibility to reduce health inequities for those using or exposed to those products every day. This includes residents, workers, installers, and the communities that surround the facilities where these materials are processed and disposed of. By making material health a priority in your decision-making processes, you’ll be joining efforts to tackle the root causes of health inequities in communities around the world. Visit informed.habitablefuture.org to learn how our building product guidance can help you make better material choices.

Health Care Without Harm Europe advocates for the complete elimination of PVC due to its environmental impact, urging policymakers to develop a strategy for its phase-out in Europe.

If we are to have any chance of addressing the global plastics crisis, Polyvinyl Chloride plastic (PVC) also known as vinyl, has got to go.

It cannot be produced sustainably or equitably. It cannot be “optimized.” It cannot be recycled. It will never find a place in a circular economy, and it makes it harder to achieve circularity with other materials, including other plastics.

There are three reasons for this: technical, economic, and behavioral. The inherent qualities of PVC and its cousin, CPVC, make it among the most technologically challenging plastics to recycle. Like most plastics, PVC is made with fossil fuel feedstocks. Unlike other plastics, PVC/vinyl also contains substantial amounts of chlorine, upwards of 40%. This is the C in PVC, and this chlorine content adds an additional layer of negative impacts to the earth and its people, social inequity, and an impediment to recycling that cannot be overcome. Recyclers consider it a contaminant to other plastic feedstock streams.1 It mucks up the machines and the already perilous economics of plastics recycling.

There is an emerging global consensus on this point, albeit euphemistically stated. The Ellen MacArthur New Plastics Economy Project consists of representatives from the world’s largest plastic makers and users, along with governments, academics, and NGOs. In 2017 it reached the conclusion that PVC was an “uncommon” plastic that was unlikely to be recycled and should be avoided in favor of other more recyclable packaging materials.2 “Uncommon” in the diplomatic parlance of international multistakeholder initiatives means unrecyclable. The project also took note of the many toxic emissions associated with PVC production.

That’s not surprising since after 30 years of hollow promises and pilot projects doomed to fail, virtually no post-consumer PVC is recycled.3 Conversely, leading brands with forward-looking materials policies such such as Nike, Apple, and Google have prioritized PVC phase outs.4

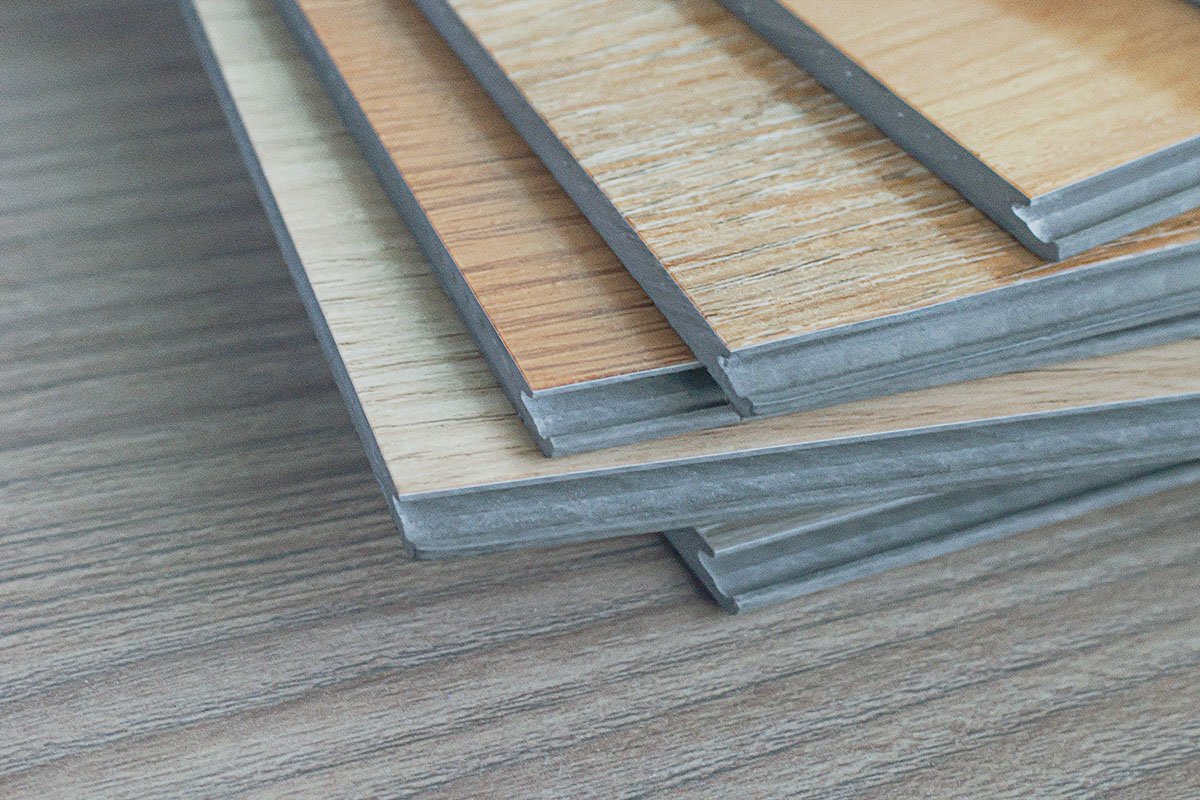

But in the building industry, PVC rages on. Virgin vinyl LVT flooring is the fastest growing product in the flooring sector. So much so that in 2017 sustainability leader Interface introduced a new product line of virgin vinyl LVT, despite forecasting just one year before that by 2020 the company would “source 95 percent of its materials from recycled or biobased resources.”5

The current flooring market demands the impossible – aesthetic qualities and durability at a price unmatchable by non-vinyl floor coverings. A price that is unmatchable because at every stage of vinyl production, the societal costs of its poisonous environmental health consequences are externalized, subsidized, paid for by the people who live in communities that have become virtual poster children for environmental injustice and oppression. Places like Mossville, LA; Freeport, TX; and the Xinjiang Province in China, home to the oppressed Uighur population. As we detail in our exhaustive Chlorine and Building Materials report, the unique chlorine component of PVC plastic contributes to a range of toxic pollution problems starting with the fact that chlorine production relies upon either mercury-, asbestos-, or PFAS-based processes. This is in addition to the onerous environmental health burdens of petrochemical processing that burden all plastics.

It is true that all plastics contribute to environmental injustices. Virtually all plastics are made from fossil fuel feedstocks, and all plastics share abysmally low recovery and cycling rates. Still, independent experts agree that some plastics are worse than others, and PVC is among the worst.6 Additionally, most uses of PVC have readily available alternatives or solutions that are within reach. Certainly there are non-PVC alternatives for flooring. What can’t be beat is the cost – that is, the low purchase price at the point of sale, subsidized by the sacrifices we ignore in the communities where the plastics are manufactured and the waste is dealt with. And BIPOC communities bear the disproportionate burden of it all. Acknowledging and addressing this tradeoff is at the root of the behavioral change that stands between us and a just and healthy circular economy.

In his influential book How To Be An Antiracist, Dr. Ibram X. Kendi argues that if we recognize we live in a society with many racial inequities – and acknowledge that since no racial group is inferior or superior to another, the cause of these inequities are policies and practices – then to be anti-racist is to challenge those policies and practices where we can and create new ones that create equity and justice for all.

Imagine if as part of our commitment to equity in our sustainability efforts, we recognized, acknowledged, and did what we could to address the racial inequities associated with PVC production, and committed right now to stop using PVC unless it was absolutely essential. The plastics industry would howl and point out inconsistencies, question priorities, highlight unintended consequences. We would all feel a tinge of whataboutism – what about carbon, or this other injustice, or that shortcoming of the alternatives. But it is clear that widespread incrementalism is failing us on so many fronts, none more than the environmental injustices that are hardwired into our supply chains.

In fact, there are many examples of companies and building projects that have prioritized PVC-free alternatives based upon principles of equity and justice. We need more leaders in the field to join those who are abandoning vinyl in product types that have superior options. Our CEO Gina Ciganik used a non-PVC flooring in 2015 at The Rose, her last development project prior to joining HBN.

First Community Housing, another affordable housing leader, has been using linoleum for many years for similar reasons. In their Leigh Avenue Apartments project. Forbo’s Marmoleum Click tiles were the flooring of choice.

Vinyl is not an essential material for any of the largest surface areas of our building projects – flooring, wall coverings, or roofing. It may often be the conventional choice in conventional buildings, but it should not be the conventional choice in buildings that promise to be green, healthy, and equitable. LVT may be the fastest growing flooring product in the world, but it is a throwback to the inequitable, unsustainable world we say is unacceptable, not the world we are trying to create.

Habitable can help you start by using our Informed™ product guidance, which helps identify worst and best in class products that are healthier for people and the planet. So why not start here and now, with a principled stand of refusing to profit from unjust, frequently racist, externalized costs?

SOURCES

- https://plasticsrecycling.org/pvc-design-guidance

- See pp. 27-29: www.newplasticseconomy.org/assets/doc/New-Plastics-Economy_Catalysing-Action_13-1-17.pdf

- See e.g. Figure 1: https://css.umich.edu/publication/plastics-us-toward-material-flow-characterization-production-markets-and-end-life

- See e.g.: www.apple.com/environment/answers (Apple); www.greenpeace.org/usa/reports/greener-electronics-2017 (Google); www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-aug-26-fi-16540-story.html (Nike)

- www.greenbiz.com/article/inside-interfaces-bold-new-mission-achieve-climate-take-back: “Going Beyond Zero” The march towards Mission Zero continued unabated, however, with consistent year-over-year improvement in most metrics. Today, the company forecasts that by 2020 it will halve its energy use, power 87 percent of its operations with renewable energy, cut water intake by 90 percent, reduce greenhouse gas emissions 95 percent (and its overall carbon footprint by 80 percent), send nothing to landfills, and source 95 percent of its materials from recycled or biobased resources.

- www.cleanproduction.org/resources/entry/plastics-scorecard-press-release

My daughter is nine, and she is going through the first stages of puberty.

This is four years before I reached that stage and two years before any of my three sisters or sister-in-law hit this developmental milestone. While nine is still considered in the normal developmental range for girls in the United States, it is certainly early compared to the women in my generation.

As HBN’s Chief Research Officer, it is my job to understand the impacts that different chemicals can have on human health and work every day to help people make informed decisions about the products they use. As a mother, it is also my job to keep my kids safe. While my research will not help me answer the question about why my daughter may be going through puberty earlier than I did, I can share what I have learned about chemicals found in building materials and their potential impacts on children’s health in the hope that you can join me in making the best decisions we can for our future generations.

While this article will focus on one environmental factor (exposure to pollutants related to the use of building products), I recognize this is one of many factors that impact children’s health. These include biological factors (e.g. sex, genetics, age), social factors (e.g. income, culture), and environmental factors (e.g. diet, exposure to pollutants).1 With this in mind, this article does not tie specific products or chemicals to specific health outcomes in children. Instead, this article discusses two groups (or classes) of chemicals used in building products that are known to have reproductive toxicity or endocrine disrupting concerns and are found both in household dust and children’s bodies.

Children are not little adults. For example, my five year old likes to sleep in a small cardboard box at night these days with his neck at an angle that would take me weeks to uncrick. They also eat more, inhale more, and drink more than adults per kilogram body weight.2 They also spend more time on the floor (see box story above) and are therefore more likely to ingest or inhale household dust. Their immune and metabolic systems are not fully developed, so their bodies process and eliminate chemicals differently than adults. Lastly, children’s bodies are in a constant state of growth and development, and as such they can be more sensitive to chemicals than adults.3

Let’s explore two groups of chemicals found in building products and in children’s bodies that can impact the endocrine systems.

Bisphenols

Bisphenols are a group of chemicals including bisphenol A (BPA) and bisphenol S (BPS). BPA is on the EU Substances of Very High Concern (SVHC) list due to endocrine disrupting properties. Specifically, many bisphenols mimic the hormone estrogen. BPA is considered “Toxic to Reproduction” by the European Chemicals Agency. Bisphenols are found in many different types of products including plastic items, paper receipts, and metal food and beverage can liners. In building products, BPA-related compounds are found in “epoxy” resin products, for example, epoxy flooring adhesive and epoxy fluid-applied flooring.

In last year’s article, “There’s What In My Body?” I shared how I found BPA and BPS in my body through a biomonitoring study by Silent Spring. Compared to other participants in the study, I had lower levels of BPA but higher levels of BPS, a common replacement for BPA. I was surprised and disturbed by the results, and I cannot help but wonder what my daughter’s levels would be today if we tested for bisphenols or any of the other endocrine disrupting compounds found in household products. Levels of BPA in children are typically higher than for adults. Most importantly, even tiny amounts of endocrine disrupting chemicals, including BPA, can lead to health and behavioral problems in developing children.4 For example, increasing urinary BPA levels in children are linked to an increase in behavioral regulation problems, anxiety, and hyperactivity.

The good news is that bisphenols are rapidly metabolized. If you can identify and remove sources of bisphenols from your home and diet, you can reduce your exposure.

Orthophthalates

Orthophthalates are a group of chemicals used as plasticizers – additives that make plastics more flexible. Orthophthalates can be developmental toxicants per the U.S. National Toxicology Program.5 Some common orthophthalates interfere with the production of testosterone, which can have irreversible effects on the male reproductive system. Higher exposure to certain orthophthalates has been associated with higher incidences of preterm birth; in particular, mothers who had consistently higher exposures to orthophthalates were five times more likely to experience spontaneous preterm birth (Ferguson et al 2014, JAMA Pediatrics). Preterm birth is associated with a variety of adverse health outcomes including increase in disability as young adults.6

Orthophthalates are sometimes called “everywhere chemicals” because they are so common in household products. With respect to building products, up until recently orthophthalates were prevalent in vinyl flooring. While the vinyl flooring industry has largely phased them out of new products, many homes with vinyl flooring installed before 2015 will still likely contain orthophthalate plasticizers. Orthophthalates can also be found in sealants used throughout the home. While the sealant industry is beginning to phase out these chemicals, they are still commonly used.

Similar to bisphenols, phthalates are metabolized quickly, so identifying potential sources and removing those from the home is the easiest way to reduce exposure. Possible sources include older plastic toys, cleaning products, personal care products, sealants, older vinyl flooring (pre-2018), and fragrances.

My daughter is not an outlier. Over the last 40 years, the average age of initial onset of puberty has decreased by 12 months. There are likely multiple reasons for this trend. However, an increase in exposure to a cocktail of endocrine disruptors is a possible explanation. Collectively, we can use our voices and buying power to shift the market towards safer products.

What can you do to help?

- You can step up out of red and choose products that are ranked ideally yellow or green through Informed™

- Ask your retailer to keep products containing hazardous chemicals off of the shelves. The Mind the Store campaign by Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families encourages retailers to move away from phthalates, bisphenols, and other hazardous chemicals. Hot off of the presses is the latest Retailer Report Card. See how your favorite retailer stacks up.

- Support legislation that uses the class-based approach to ban problematic chemicals. The Green Science Policy Institute develops research and supports policies that prevent the use of “Six Classes of Harmful Chemicals”. By reducing the use of entire classes of chemicals, we reduce the chance for regrettable substitution and the inefficiencies and dangers associated with a one-at-a-time or “toxic whack-a-mole” approach to chemical restrictions. In addition to bisphenols and phthalates, GSPI’s Six Classes include per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS), antimicrobials, flame retardants, some solvents, and certain metals. Numerous state legislatures have passed laws restricting the use of bisphenols and phthalates in a variety of products.

SOURCES

- Commission and for Environmental Cooperation. “Toxic Chemicals and Children’s Health in North America: A Call for Efforts to Determine the Sources, Levels of Exposure, and Risks That Industrial Chemicals Pose to Children’s Health,” 2006. http://www3.cec.org/islandora/en/item/2280-toxic-chemicals-and-childrens-health-in-north-america-en.pdf.

- Miller, Mark D., Melanie A. Marty, Amy Arcus, Joseph Brown, David Morry, and Martha Sandy. “Differences between Children and Adults: Implications for Risk Assessment at California EPA.” International Journal of Toxicology 21, no. 5 (October 2002): 403–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10915810290096630.

- Commission and for Environmental Cooperation. “Toxic Chemicals and Children’s Health in North America: A Call for Efforts to Determine the Sources, Levels of Exposure, and Risks That Industrial Chemicals Pose to Children’s Health,” 2006. http://www3.cec.org/islandora/en/item/2280-toxic-chemicals-and-childrens-health-in-north-america-en.pdf.

- Braun, Joe M., and Russ Hauser. “Bisphenol A and Children’s Health.” Current Opinion in Pediatrics 23, no. 2 (April 2011): 233–39. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283445675.

Braun, Joe M., Amy E. Kalkbrenner, Antonia M. Calafat, Kimberly Yolton, Xiaoyun Ye, Kim N. Dietrich, and Bruce P. Lanphear. “Impact of Early-Life Bisphenol A Exposure on Behavior and Executive Function in Children.” Pediatrics 128, no. 5 (November 2011): 873–82. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1335. - “NTP-CERHR Monograph on the Potential Human Reproductive and Developmental Effects of Di-Isodecyl Phthalate (DIDP).” National Toxicology Program, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Center for the Evaluation of Risks to Human Reproduction, NIH Publication No. 03-4485. April 2003.

- Lindström, Karolina, Birger Winbladh, Bengt Haglund, and Anders Hjern. “Preterm Infants as Young Adults: A Swedish National Cohort Study.” Pediatrics 120, no. 1 (July 2007): 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-3260.

For years, Habitable has been thinking about and consulting with our partners about how to describe the impact of choosing healthier building products. Here’s why this is a complex and challenging issue for the industry:

- Incomplete knowledge of what many building products are made of

- Limited understanding of the health hazards of the thousands of chemicals in commerce today

- Trade-offs when making material choices

These reasons drive the need for full transparency of chemical contents and full assessment of chemical hazards. This can ultimately lead to optimizing products in order to avoid hazardous chemicals.

Toxic chemicals have a huge and complex impact on the health and well-being of people and the environment. Those impacts are spread throughout a product’s life cycle. For example, fenceline communities can be exposed during the manufacturing of products in adjacent facilities, workers can be exposed on the job during the manufacturing and installation processes, and building occupants can be exposed during the product’s use stage. Some individuals suffer multiple exposures because they are affected in all of those instances.

In addition, toxic chemicals can be released when materials are disposed of or recycled. When they incorporate recycled content into new products, manufacturers can include legacy toxicants, inhibiting the circular economy and exposing individuals to hazardous chemicals—even those that have been phased out as intentional content in products.

We know intrinsically that hazardous chemicals have the potential to do harm and that they commonly do so. For champions of this cause, that understanding of the precautionary principle is enough. Others still need to be convinced and often want to quantify the impact of a healthy materials program. How can healthy building champions start to talk about and quantify the impacts of material choices?

Broad Impacts of Toxic Chemicals

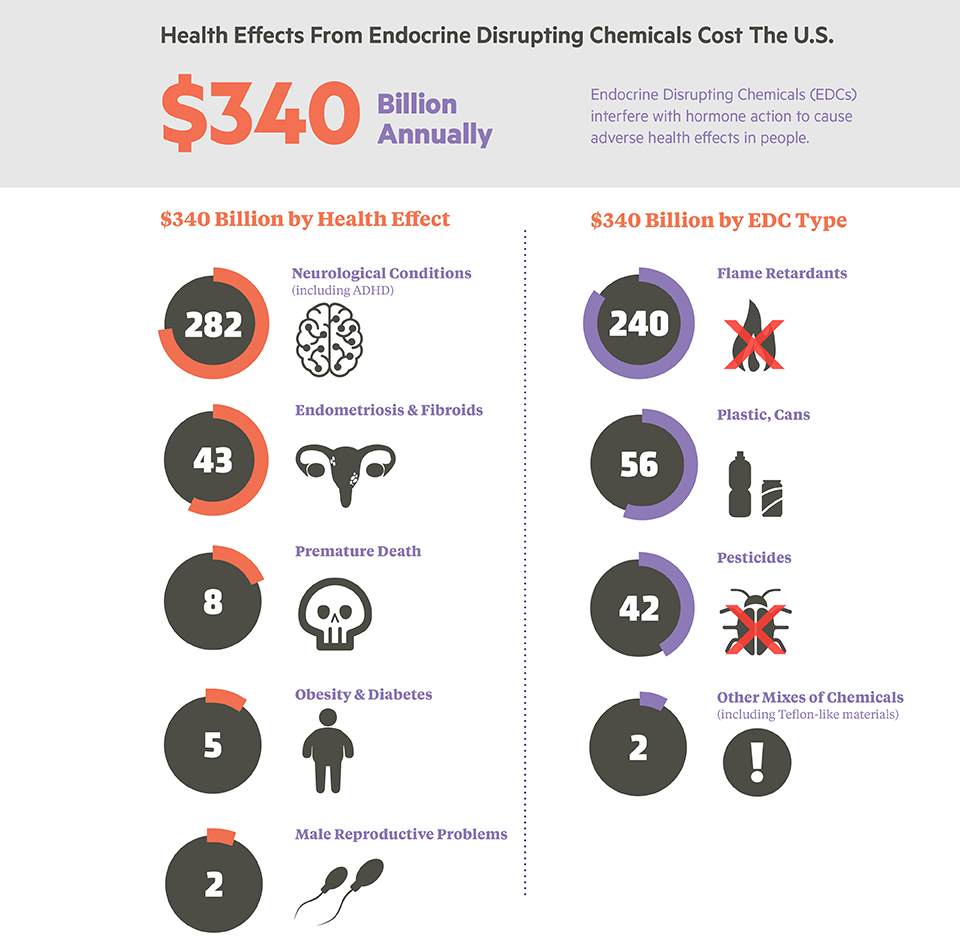

One way researchers quantify the impact of chemicals is to consider the broad economic impacts of chemical exposures. Evidence increasingly shows that toxic chemical exposures may be costing the USA billions of dollars and millions of IQ points. One recent study estimates that certain endocrine-disrupting chemicals cost the United States $340 billion each year. This is a staggerring 2.3% of the US gross domestic product.1 And that is for only a subset of the hazardous chemicals that surround us every day. These numbers provide important context for the larger discussion of toxic chemical use, but cannot easily be tied to daily decisions about specific materials.

Market Scale Impacts

For years, Habitable has been targeting orthophthalates in vinyl flooring as a key chemical and product category combination to be avoided. Orthophthalates can be released from products and deposited in dust which can be inhaled or ingested by residents—particularly young children who crawl on floors and often place their hands in their mouths3. By systematically reducing chemicals of concern in common products, we can all work together to continue to affect this scale of change in the marketplace and keep millions more tons of hazardous chemicals out of buildings.

Impacts on the Project Scale

Context is key for understanding the impact chemical reduction or elimination can have—a pound of one chemical may not have the same level of impact as a pound of another chemical. But, given the right context, this sort of calculation may prove useful as part of a larger story. The following examples provide context for the story of different impacts of different chemicals.

- Small decisions, big impacts: While many manufacturers and retailers have phased out hazardous orthophthalate plasticizers, some vinyl flooring may still contain them. If we consider an example affordable housing project, avoiding orthophthalates in flooring can keep dozens of pounds of these hazardous chemicals out of a single unit (about the equivalent of 10 gallons of milk).4 For a whole building, this equates to several tons of orthophthalates that can be avoided.5 It is easy to see how this impact quickly magnifies in the context of a broader market shift.

- Little things matter: Alkylphenol ethoxylates (APEs) in paints are endocrine-disrupting chemicals make up less than one percent of a typical paint. In this case, by making the choice to avoid APEs, a couple of pounds of these hazardous chemicals are kept out of a single unit (about the equivalent of a quart of milk). This translates to a couple of hundred pounds kept out of an entire building.6 This quantity may seem small compared to the tons avoided in the phthalate example above, but little things matter. Small exposures to chemicals can have big impacts, particularly for developing children.7 And, since our environments can contain many hazardous chemicals, and we aren’t exposed to just a single chemical at a time, these exposures stack up in our bodies.8

- Reducing exposure everywhere: Choosing products without hazardous target chemicals keeps them out of buildings, but can also reduce exposures as these products are manufactured, installed, and disposed of or recycled. Some chemicals may have impacts that occur primarily outside of the residence where they are installed, but these impacts can still be significant. Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), for example, a primary component of vinyl flooring, requires toxic processes for its production and can generate toxic pollution when it is disposed of. Manufacturing of the PVC needed to create the vinyl flooring for one building as described above can release dozens of pounds of hazardous chlorinated emissions, impacting air quality in surrounding communities.9 These fenceline communities are often low-income, and suffer from disproportionate exposure in their homes, through their work, and from local air pollution. If choosing non-vinyl flooring for a single building can help reduce potential exposure to hazardous chlorinated emissions in these fenceline communities, imagine the potential impacts of avoiding vinyl on a larger scale!

In addition to information about target chemicals to avoid, our Informed™ product guidance provides recommendations of alternative types of materials that are typically better from a health hazard perspective and includes steps to work toward the goal of full transparency of product content and full assessment of chemical hazards. This framework can help ensure that toxic chemicals and regrettable substitutions are avoided.

Each decision you make about the materials you use, each step toward using healthier products, can have big impacts within a housing unit, a building, and in the broader environment. Collectively, these individual decisions also influence manufacturers to provide better, more transparent products for us all. Ultimately, this can reduce the hazardous chemicals not just in our buildings but also in our bodies.

SOURCES

- Attina, Teresa M, Russ Hauser, Sheela Sathyanaraya, Patricia A Hunt, Jean-Pierre Bourguignon, John Peterson Myers, Joseph DiGangi, R Thomas Zoeller, and Leonardo Trasande. “Exposure to Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in the USA: A Population-Based Disease Burden and Cost Analysis.” The Lancet 4, no. 12 (December 1, 2016): 996–1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30275-3.

- “Disease Burden & Costs Due to Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals.” NYU Langone Health, July 12, 2019. https://med.nyu.edu/departments-institutes/pediatrics/divisions/environmental-pediatrics/research/policy-initiatives/disease-burden-costs-endocrine-disrupting-chemicals.

- Bi, Chenyang, Juan P. Maestre, LiG Hongwan, GeR Zhang, Raheleh Givehchi, Alireza Mahdavi, Kerry A. Kinney, Jeffery Siegel, Sharon D. Horner, and Ying Xu. “Phthalates and Organophosphates in Settled Dust and HVAC Filter Dust of U.S. Low-Income Homes: Association with Season, Building Characteristics, and Childhood Asthma.” Environment International 121 (December 2018): 916–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.09.013.; Mitro, Susanna D., Robin E. Dodson, Veena Singla, Gary Adamkiewicz, Angelo F. Elmi, Monica K. Tilly, and Ami R. Zota. “Consumer Product Chemicals in Indoor Dust: A Quantitative Meta-Analysis of U.S. Studies.” Environmental Science & Technology 50, no. 19 (October 4, 2016): 10661–72. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b02023.

- According to the USDA, milk typically weighs about 8.6 pounds per gallon. See: “Weights, Measures, and Conversion Factors for Agricultural Commodities and Their Products.” United States Department of Agriculture, June 1992. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/41880/33132_ah697_002.pdf?v=0.

- HBN used the Common Products for Luxury Vinyl Tile and Vinyl Sheet to estimate the amount of plasticizer. We assumed a 100 unit building of 1000 square foot two-bedroom apartments with vinyl flooring throughout the units.

- HBN used the Common Product profiles for Eggshell and Flat Paint to estimate the amount of surfactant and assumed a 100 unit building of 1000 square foot two-bedroom apartments.

- Vandenberg, Laura N., Theo Colborn, Tyrone B. Hayes, Jerrold J. Heindel, David R. Jacobs, Duk-Hee Lee, Toshi Shioda, et al. “Hormones and Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: Low-Dose Effects and Nonmonotonic Dose Responses.” Endocrine Reviews 33, no. 3 (June 1, 2012): 378–455. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2011-1050.

- Impacts can be additive, where health impacts are equal to the sum of the effect of each chemical alone. They can also be synergistic, where the resulting health impacts are greater than the sum of the individual chemicals’ expected impacts.

- HBN used the Common Products for Luxury Vinyl Tile and Vinyl Sheet to estimate the amount of PVC. We assumed a 100 unit building of 1000 square foot two-bedroom apartments with vinyl flooring throughout the units. Emissions are based on the Calvert City, KY Westlake plant examined in HBN’s Chlorine and Building Materials Project. According to EPA’s EJScreen tool, the census blockgroup where this facility is located is primarily low income, with 62% of the population considered low income (putting this census block group in the 88th percentile nationwide in terms of low income population). EJScreen, EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool (Version 2018). Accessed March 18, 2019. https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/.

Health

Health Pollution

Pollution Equity

Equity