READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORTThe Louisville Charter for Safer Chemicals, endorsed by over 100 organizations, confronts the chemical industry’s role in the climate crisis and provides guidance for advancing environmental justice in communities disproportionately affected by harmful chemical exposure.

Coming Clean and EJHA teamed up with NRDC, Rashida Jones, and Molly Crabapple to tell the stories of vulnerable fenceline communities living near over 12,000 high-risk chemical facilities in America, urging action to protect their health and safety.

If we say climate change, what is the first thing that pops into your head? It’s probably not the impact of toxic chemicals on the environment.

Some people can probably name a chemical that contributes to climate change, whether that is carbon dioxide or methane. But what about other chemicals that you are not as familiar with? In the building materials world, these may include fluorinated blowing agents used in some foam insulation. The agents either have high global warming potential (GWP) or use chemicals in their production that have high GWP.1 Another example is the release of the toxic, global warming, and ozone-depleting chemical carbon tetrachloride in the enormous supply chain of vinyl products, otherwise known as poly vinyl chloride (PVC).2 Purveyors of vinyl products, you may unwittingly be contributing to global warming!

Yes, the way in which certain chemicals contribute to climate change is important, but this interplay is not the only consequence of chemicals on our climate. Climate change is also altering how toxic chemicals impact our health and the health of the environment – as the world warms, reducing our exposure to toxic chemicals becomes ever more important.

Five Reasons Why Climate Change and Toxic Chemicals are Connected

- Temperatures affect how chemicals behave – warmer temperatures increase our exposure to toxic chemicals—.3 Higher temperatures can allow certain chemicals to vaporize more easily and enter the air we breathe.4 Warmer temperatures on Earth can also encourage the breakdown of some chemicals into toxic byproducts.5

- Impacts of extreme weather events include concentrated releases of chemicals—catastrophic weather-related events such as hurricanes, fires, etc. can result in the release of toxic chemicals into the air when homes burn, or as factories in the Gulf region are damaged or destroyed.6 These events are becoming more and more frequent and will continue to expose people and the planet to highly concentrated chemical doses.

- Climate change can exacerbate the health impacts of air pollution—volatile organic compounds released by chemical products contribute to the production of smog, leading to poor air quality which can negatively impact the lungs or exacerbate respiratory diseases such as asthma or Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.7 Warmer temperatures amplify these impacts.8 As the largest source of air pollutants slowly transitions from transportation sources to chemical products, and as the earth warms, smart product choices will have even more impact on air quality.9

- Toxic chemicals may hinder the body’s ability to adapt to climate change—in recent years, studies discovered that many toxic chemicals are endocrine disruptors.10 Animal studies have highlighted that endocrine-disrupting chemicals can alter metabolism and hinder animals’ ability to adapt to changing temperatures.11 While these findings were in animals, similar effects occur in humans as well, particularly in communities without access to heating or air conditioning.

- Toxic chemicals increase communities’ vulnerability to climate change effects—toxic chemicals are an environmental justice issue. Ever heard of Cancer Alley? Cancer Alley is a predominantly African American community located in Southern Louisiana right next door to factories pumping out toxic chemicals every day.12 This 100 mile stretch of land is home to 25 percent of the nation’s petrochemical manufacturing and a large portion of its PVC supply chain.13 Aptly named, the cancer rate in this area is higher than the state and national cancer rate.14 Cancer Alley’s location right next to the Gulf Coast also increases its vulnerability to hurricanes and tropical storms. As climate change increases the frequency of extreme weather events, the impacts of toxic chemicals on this community also deepens.

Caring About Toxic Chemicals Can Help Mitigate the Impact of Climate Change—For You!

While most toxic chemicals do not cause climate change, they do affect how climate change might impact you. These impacts compound as more chemicals are produced or utilized.15 In 1970, the U.S. produced 50 million tons of synthetic chemicals.16 In 1995, the number tripled to 150 million tons, and today, that number continues to increase.17

Very few of the tens of thousands of chemicals on the marketplace are fully tested for health hazards, and details on human exposure to these chemicals are limited.18 We are exposed to these chemicals every day, in varying quantities and mixtures. Over a lifetime, the small exposures add up. Predictions of health outcomes from long-term exposure are already fuzzy at best, but add on the component of climate change and the mystery deepens.19 While researchers continue to study climate change and chemicals to answer the questions we have, there are steps that we can take to help mitigate the negative impact of climate change on chemicals.

Habitable’s Small Piece of the Pie — How We’re Keeping Consumers Safe

We cannot remove all chemicals from our lives and many play important roles, but, we can follow the precautionary principle. If there is a less toxic chemical or product available that meets our requirements, we should use it. At Habitable, our work is guided by the precautionary principle—otherwise known as ‘better to be safe than sorry.’ Our chemical and product guidance provides advice on better products.Empowering industry to choose safer chemicals and products helps reduce the burden of toxic chemicals on all people and the planet – especially our most vulnerable populations.

Why We Can and Must Do Better

Between climate change and toxic chemicals, it could be easy to push toxic chemicals to the side as a someday problem and choose to tackle climate change first. But the truth is that the impacts of toxic chemicals are real and happening today and will only get worse in a warming world. These two issues are connected and influence each other’s outcomes. Climate change is having a significant impact on our world, but prioritizing reduction of toxic chemicals can reduce the negative consequences that climate change will have on chemicals, and consequently on us.

SOURCES

- Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) are being phased out as blowing agents in plastic foam insulation due to regulatory action in the United States. Starting in January of 2020, they are no longer allowed in most spray foam insulation. Extruded polystyrene (XPS) insulation manufacturers have until January of 2021 to phase out HFCs. The commonly used HFC in XPS, HFC-134a has a global warming potential 1,430 times that of carbon dioxide. A common replacement blowing agent for HFCs is a hydrofluoroolefin (HFO). While the HFO itself has a low GWP, it still uses high GWP chemicals in its production and may release these chemicals when it is made. See “Making Affordable Multifamily Housing More Energy Efficient: A Guide to Healthier Upgrade Materials,” Healthy Building Network, September 2018, https://informed.habitablefuture.org/resources/research/11-making-affordable-multifamily-housing-more-energy-efficient-a-guide-to-healthier-upgrade-materials.; “Substitutes in Polystyrene: Extruded Boardstock and Billet.” United States Environmental Protection Agency: Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP). Accessed Sept 16, 2019. https://www.epa.gov/snap/substitutes-polystyrene-extruded-boardstock-and-billet.; “Substitutes in Rigid Polyurethane: Spray.” United States Environmental Protection Agency: Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP). Accessed Sept 16, 2019. https://www.epa.gov/snap/substitutes-rigid-polyurethane-spray.

- Vallette, Jim. “Chlorine and Building Materials: A Global Inventory of Production Technologies, Markets, and Pollution – Phase 1: Africa, The Americas, and Europe.” Healthy Building Network, July 2018. https://habitablefuture.org/resources/chlorine-building-materials-project-phase-1-africa-the-americas-and-europe/.

- Pamela D. Noyes et al., “The Toxicology of Climate Change: Environmental Contaminants in a Warming World,” Environment International 35, no. 6 (August 1, 2009): 971–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2009.02.006.

- Noyes et al.

- Pamela D. Noyes and Sean C. Lema, “Forecasting the Impacts of Chemical Pollution and Climate Change Interactions on the Health of Wildlife,” Current Zoology 61, no. 4 (August 1, 2015): 669–89, https://doi.org/10.1093/czoolo/61.4.669.

- Caroline C. Ummenhofer and Gerald A. Meehl, “Extreme Weather and Climate Events with Ecological Relevance: A Review,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 372, no. 1723 (June 19, 2017): 20160135, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0135.

- C. M. Zigler, C. Choirat, and F. Dominici, “Impact of National Ambient Air Quality Standards Nonattainment Designations on Particulate Pollution and Health.,” Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.) 29, no. 2 (March 2018): 165–74, https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000777.

- “Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs).” Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.pca.state.mn.us/air/volatile-organic-compounds-vocs.

- Brian C. McDonald et al., “Volatile Chemical Products Emerging as Largest Petrochemical Source of Urban Organic Emissions,” Science 359, no. 6377 (February 16, 2018): 760–64, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaq0524.

- Research Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, and Institute of Medicine, The Challenge: Chemicals in Today’s Society (National Academies Press (US), 2014), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK268889/.

- Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Practice, and Medicine.

- Wesley James, Chunrong Jia, and Satish Kedia, “Uneven Magnitude of Disparities in Cancer Risks from Air Toxics,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 9, no. 12 (December 2012): 4365–85, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9124365.

- James, Jia, and Kedia.; Vallette.

- James, Jia, and Kedia.

- Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Practice, and Medicine.

- Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Practice, and Medicine

- Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Practice, and Medicine.

- Pamela D. Noyes and Sean C. Lema, “Forecasting the Impacts of Chemical Pollution and Climate Change Interactions on the Health of Wildlife,” Current Zoology 61, no. 4 (August 1, 2015): 669–89, https://doi.org/10.1093/czoolo/61.4.669

- Noyes and Lema.

Symptoms of “sick building” syndrome include “headache; eye, nose, or throat irritation; dry cough; dry or itchy skin; dizziness and nausea; difficulty in concentrating; fatigue; and sensitivity to odors”.1

These symptoms can develop after long-term exposures, or they can occur after a single instance of exposure, as in the case reported by the Minnesota Daily last month.2 Three carpet installers were sent to the emergency room after installing carpeting in an apartment building intended for student housing near the University of Minnesota. The workers could not tell doctors what they were exposed to because the carpeting did not include a complete list of contents. To find out, the workers first measured the air quality with a device ordered off of Amazon, which immediately “jumped to red” when exposed to the carpeting. The Minneapolis Building and Construction Trade Council then sent carpet samples to a lab for emissions testing. This testing found total volatile organic compounds (TVOCs) at levels that “significantly exceed” typical levels in the air. The chemicals noted on the report included some on the Minnesota Department of Health list of Chemicals of High Concern.3

What we know is that there is no law or regulation that requires building product manufacturers to disclose all product content. One of the workers interviewed for the report said he has persistent symptoms including impaired memory function, ringing in his ears, and fatigue. Because current regulations will not protect consumers, workers, or building occupants from toxic chemicals in building products, it is up to building owners, designers, specifiers, architects, other AEC professionals to know better, so we can do better. This story highlights the need for full disclosure of building materials. Until that becomes the norm, use our InformedTM product guidance to identify building products–like carpet–that are healthier for people and our planet.

After ventilating the student housing building in Minneapolis, the city’s initially “high chemical readings” dropped. According to the Minnesota Daily article, the city’s inspections show the levels are now safe. Meanwhile, one of the workers who was initially sickened by the incident was an independent contractor and therefore ineligible for workers’ compensation for the symptoms he is still experiencing months later. This and future incidents are preventable. Safer selection of materials begins with product transparency.

SOURCES

- EPA, 1991.Air and Radiation (6609J). “Indoor Air Facts No.4: Sick Building Syndrome” Factsheet” (https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-08/documents/sick_building_factsheet.pdf)

- MN Daily. 2019. “Chemical analysis finds potential health risks for former workers at the arrow” (https://mndaily.com/201203/news/ftprimeplace2/)

- chemicals found in testing of the carpet as cited in the MN Daily report included: ethyl hexanol and multicomponent solvents: “possibly naphtha, Stoddard solvent or petroleum distillate”. Naphtha, also known as Stoddard solvent is MDH chemical of high concern.

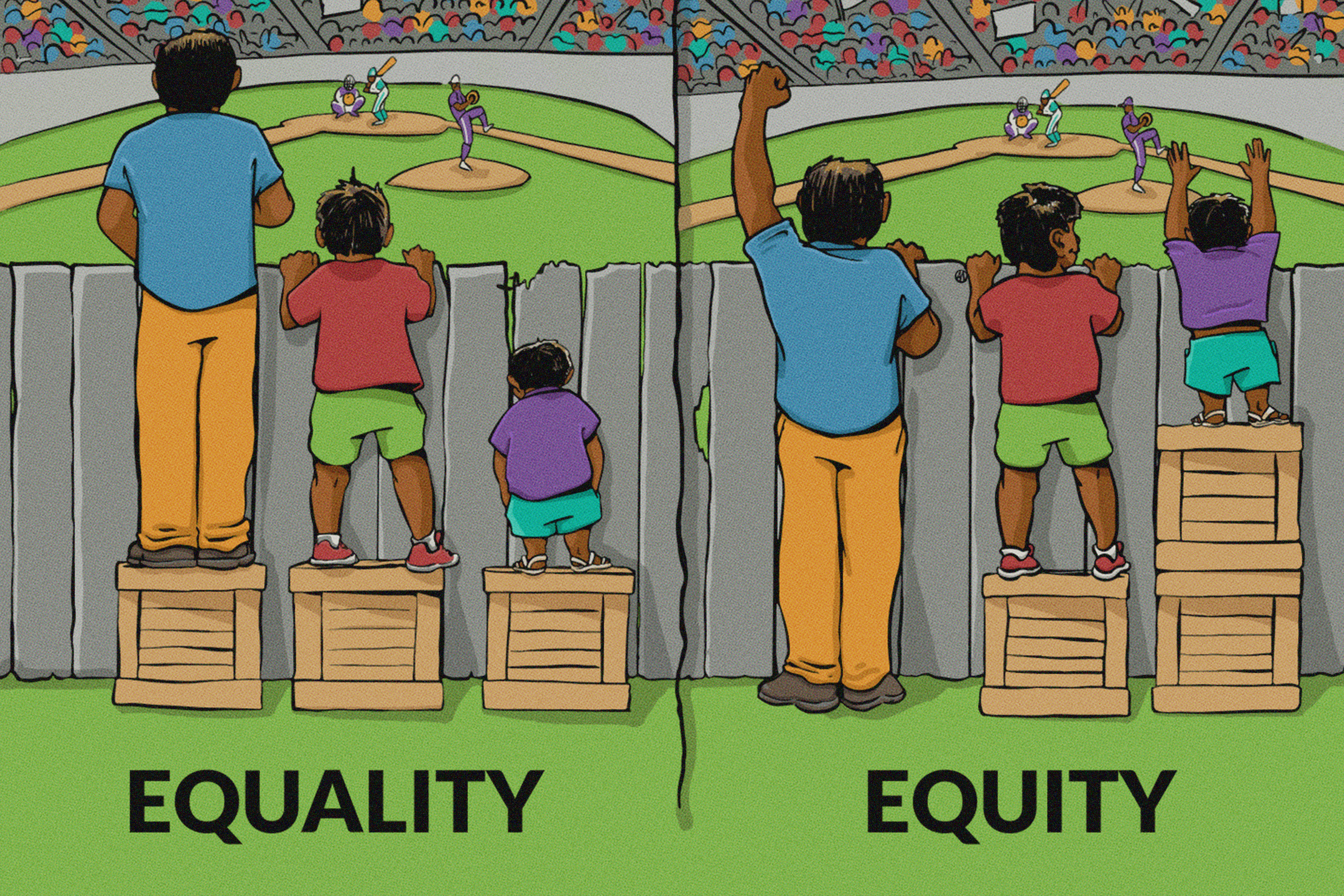

A whole lot of meaning is packaged in the word equity—a term Webster’s defines as “fairness or justice in the way people are treated.” However, the easiest way to understand equity is often through pictures, like the one below.

While this photo considers height as an inequity, in real life, income, access to food and health care are often at the heart of equity discussions. Surprisingly, a critical topic often overlooked in the equity discussion is where we spent 90 percent of our lives—in buildings.1

Oregon Metro, otherwise known simply as Metro, released a report discussing toxics reduction and equity. Its section on building materials connects building materials and equity, calling attention to the need to reduce community exposure to toxic building materials in an equitable manner. Building materials seem harmless and inert in our homes, offices, schools, or cafes. But in 1991, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) characterized indoor air pollution as “one of the greatest threats to public health of all environmental problems”.2

A large proportion of indoor air pollution stems from building materials.3 In particular, asthmagens are of highest concern and contribute to indoor air pollution through the release of chemicals from the surface of building finishes.4 For example, carpet, furniture and wall decor release chemicals through degradation or abrasion.5 The chemicals end up in dust in our homes and can enter our bodies through the lungs, skin or mouth.6 Volatile organic compounds emitted from paints are also of concern.7 In fact, a study of children in Australia showed a strong association among indoor home exposure to VOCs and increased risk of asthma.8 Over 70 percent of building material asthmagens identified by Healthy Building Network (HBN) researchers are not covered by leading indoor air quality testing standards.9 These hazardous wastes and products used in building materials disproportionately affect historically marginalized communities of color, children and low-income families.10

Equity in housing is especially important for many families with low incomes who live in multifamily housing.11 Multifamily housing often poses challenges to achieving better air quality as pollutants easily travel between units due to inadequate ventilation. Residents are usually unable to improve building infrastructure themselves.12

Incorporating building materials into the equity discussion is only part of the solution. Product testing for chemicals of concern, biomonitoring, community health impact research, chemicals research, advocacy and education all stand to make a larger collective impact.13

For funders looking to increase diversity and equity initiatives in their grant making, the building industry provides a blooming landscape to foster substantial impact within communities. Here are some key questions to consider when funding proposals:

- What is the specific toxics reduction action?

- Are there particular populations or communities impacted more than the general population by the chemical/product/system in question?

- Does the action consider and address the structural barriers and existing resources available to a population?

- Does the recommendation ameliorate the disparity or gap in accessing resources for a marginalized community?

So often, sustainability standards and initiatives are cost prohibitive, developed for those with the most access and resources, in hopes that “someday” the solutions will trickle-down. In the meantime, children and the populations with the lowest income continue to bear the burden of toxic exposures and preventable health consequences. Habitable’s Informed™ healthy product guidance is changing that old, unsuccessful paradigm. Our resources will result in healthier products for everyone, and amplify the prospect for a healthier planet.

Visit informed.habitablefuture.org to join the movement towards a healthy future for all.

SOURCES

- Cuneo, Monica et. al. Toxics Reduction and Equity: Informing actions to reduce community risks from chemicals in products. Oregonmetro.gov, 2019. August 14, 2019. https://www.oregonmetro.gov/toxics-reduction-and-equity-study

- Ibid.

- Environmental Protection Agency. “Fundamentals of Indoor Air Quality in Buildings.” Indoor Air Quality, 1 Aug. 2018, www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/fundamentals-indoor-air-quality-buildings#Factors.

- Lott, Sarah, and Jim Vallette. Full Disclosure Required: A Strategy to Prevent Asthma Through Building Product Selection. Healthy Building Network, December 2013. August 14, 2019. https://habitablefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/93-full-disclosure-required-a-strategy-to-prevent-asthma-through-building-product-selection.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Singla, Veena. Toxic Dust: The Dangerous Chemical Brew in Every Home. Natural Resources Defense Council, September 13, 2016. August 20, 2019. https://www.nrdc.org/experts/veena-singla/toxic-dust-dangerous-chemical-brew-every-home

- Lott, Sarah, and Jim Vallette. Full Disclosure Required: A Strategy to Prevent Asthma Through Building Product Selection. Healthy Building Network, December 2013. August 14, 2019. https://habitablefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/93-full-disclosure-required-a-strategy-to-prevent-asthma-through-building-product-selection.pdf.

- Rumchev, K, et al. Association of Domestic Exposure to Volatile Organic Compounds with Asthma in Young Children. Thorax, BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, 1 Sep. 2004. August 14, 2019. http://thorax.bmj.com/content/59/9/746.

- Lott, Sarah, and Jim Vallette. Full Disclosure Required: A Strategy to Prevent Asthma Through Building Product Selection. Healthy Building Network, December 2013. August 14, 2019. https://habitablefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/93-full-disclosure-required-a-strategy-to-prevent-asthma-through-building-product-selection.pdf.

- Cuneo, Monica et. al. Toxics Reduction and Equity: Informing actions to reduce community risks from chemicals in products. Oregonmetro.gov, 2019. August 14, 2019. https://www.oregonmetro.gov/toxics-reduction-and-equity-study

- Ibid.

- Hayes, Vicky et al. Evaluating Ventilation in Multifamily Buildings. Home Energy Magazine, August 1994. August 14, 2019. www.homeenergy.org/show/article/nav/ventilation/id/1059.

- Cuneo, Monica et. al. Toxics Reduction and Equity: Informing actions to reduce community risks from chemicals in products. Oregonmetro.gov, 2019. August 14, 2019. https://www.oregonmetro.gov/toxics-reduction-and-equity-study

Asthma is a complex, heterogeneous disease, often of multifactorial origin. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported that the number of people diagnosed with asthma grew by 4.3 million during the last decade. Nearly 26 million people are affected by chronic asthma, including over eight million children.

Among asthma risk factors, health organizations have identified hundreds of substances that can cause the onset of asthma. Many of these asthmagens are common ingredients of building products like insulation, paints, adhesives, wall panels and floors. This paper identifies asthmagens found in building products, how people can be exposed to these substances, and what is known and yet-to-be known about the impacts of these exposures.

Asthma rates in the United States have been rising since at least 1980. Today, nearly 26 million people are affected by chronic asthma, including over eight million children. These rates are rising despite the proliferation of asthma control strategies, including indoor air quality pro- grams. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported that the number of people diagnosed with asthma grew by 4.3 million during the last decade from 2001 to 2009.

As asthma affects more people, it becomes increasingly clear that new strategies need to be considered, focusing on the prevention of asthma onset. Few strategies are in place that effectively prevents exposure to chemi- cals that cause asthma. Due to the complexity of this condition conventional efforts have largely focused on asthma management. Health organizations have identified a number of chemicals that are known to cause the onset of asthma, and are therefore labeled asthmagens. Since these chemicals are common ingredients of many interior finishes, like floors, carpets, and paints, it is possible to improve asthma prevention strategies by reducing or eliminating these chemicals from building materials. The Healthy Building Network (HBN) took a three-pronged approach that examined how pervasive asthmagen chemicals are in the built environment, what steps have been taken to address them, and what further actions are needed.

Lessons From The Formosa PVC Plant, Illiopolis, Illinois

One morning ten years ago, I was at work on a book about environmental health when the phone rang. It was my Uncle Roy. He wanted me to know that a developer had come to town peddling a plan to construct a giant waste incinerator in the cornfield next to his own. What the man was planning to burn in it, he said, was old auto interiors, including a lot of PVC plastic. If the people of the township went along, the company would build the school a new library.

Now how did they know we needed a library, my uncle wondered. And what did I know about a chemical called dioxin? Funny he should ask. I was just drafting that chapter.

So I took leave of the Harvard Medical School Library and went back home to library-less central Illinois to throw my hat in the ring with my mother’s brother and a group of other farmers who had vowed to fight the incinerator.

And we won. Not only did Forrest, Illinois vote down the incinerator plan, it was defeated in six other small, impoverished farming communities where the same developer had dangled it. People looked out at their turkeys, hogs, and fields of corn and imagined what could happen if one semi-truck full of dioxin-laden incinerator ash overturned on a windy day. It just wasn’t worth the risk, they decided.

A decade later, central Illinoisians are confronted with a similar choice. This time it involves the manufacture of PVC rather than its destruction.

On April 23, 2004, the PVC plant in Illiopolis, Illinois exploded, spewing fireballs into the night sky, cutting power and water, and sending all of the village’s 900-something inhabitants into makeshift shelters in distant towns. Four workers were killed instantly. Three were hospitalized.

The U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board conducted an investigation of the long-term environmental health effects of the explosion. Its chairwoman, Carolyn W. Merritt, called the explosion at Illiopolis among the most serious the agency has ever investigated. So far, no signs of air or water contamination have been uncovered. On the other hand, at this writing, investigators were not able to get closer than a quarter mile to the plant because of safety concerns.

But, let’s suppose that no chemical contamination from the plant’s destruction was found. Let’s imagine that thousands of pounds of vinyl chloride and vinyl acetate-which workers were mixing at the time of detonation-somehow all burned up without leaving behind any toxic residues in the community’s air or water or farm fields. It would still be a bad idea to rebuild this plant. Which is the current plan.

Each year, the Illiopolis PVC plant releases into the air more than 40,000 pounds of vinyl chloride, a recognized human carcinogen and reproductive toxicant. It releases another 40,000 pounds of vinyl acetate, a suspected carcinogen and neurotoxin. In other words, under normal operating conditions, this plant routinely discharges into the surrounding community more than 40 tons of toxic chemicals annually. That works out to 220 pounds of known and probable carcinogens every single day. The weight of a large man.

Such releases make this plant one of Illinois’ biggest polluters. But when you stack the Illiopolis facility next to all the other PVC plants in the United States, of which there are about 40, it pales in comparison. Its emissions are far from the worst. (Oxyvinyl in Pasadena, Texas releases more than 100,000 pounds of vinyl chloride annually.)

Even absent horrific accidents like the one in Illiopolis, which made headlines across the world, there seems to be no way of making PVC without contaminating somebody’s beloved hometown with cancer-causing substances. And that fact alone should be sufficient to compel us to seek out substitutes for PVC for all its various uses.

Here are the names of those who died in the Illiopolis explosion: Joseph Machalek, age 50; Larry Graves; age 47; Glenn Lyman, age 49; Linda Hancock, age 56.

What are the names of those who have died of cancer caused by the routine operation of this same plant over the years? Who have suffered miscarriages, birth defects, or neurological disorders due to their constant exposure to reproductive and neurological poisons? It is an unknown and unknowable number. But it may well exceed four. And it may be too high a price to pay for vinyl.

Sandra Steingraber, Ph.D., grew up in Pekin, Illinois. She is a biologist and author of the book Living Downstream: An Ecologist Looks at Cancer and the Environment. She is currently on the faculty of Ithaca College in New York.

In the last 40 years, polyvinyl chloride plastic (PVC) has become a major building material. Global vinyl production now totals over 30 million tons per year, the majority of which is directed to building applications, furnishings, and electronics.

The hazards posed by dioxins, phthalates, metals, vinyl chloride, and ethylene dichloride are largely unique to PVC, which is the only major building material and the only major plastic that contains chlorine or requires plasticizers or stabilizers. PVC building materials therefore represent a significant and unnecessary environmental health risk, and their phase-out in favor of safer alternatives should be a high priority. PVC is the antithesis of a green building material. Efforts to speed adoption of safer, viable substitute building materials can have significant, tangible benefits for human health and the environment. This report describes the full life cycle of PVC in the contemporary building industry from production to disposal.

Equity

Equity Climate Change

Climate Change Health

Health Pollution

Pollution