READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORTThis chapter in ILFI’s book The Regenerative Materials Economy explores the often overlooked life cycle chemical and environmental justice impacts of building materials, focusing on insulation materials like fiberglass and spray polyurethane foam (SPF).

Through a framework rooted in green chemistry and environmental justice principles, authors Rebecca Stamm of HBN and Veena Singla of NRDC analyze manufacturing realities, environmental justice concerns, and environmental health impacts, providing recommendations to improve the industry’s sustainability and reduce the negative effects on marginalized communities.

Simona Fischer, MSR Design

As registered architect, sustainable design professional, and associate with MSR Design, Simona Fischer has spent much of her career thus far developing and testing strategies for integrating sustainable design into the workflow of architectural practice. Her experience includes project management, Living Building Challenge documentation, and firmwide sustainable design implementation.

Simona is a dynamic community of practitioners who help co-create solutions to accelerate the adoption of healthier building materials in affordable housing. She has presented at national conferences, lectures regularly at the University of Minnesota, and currently co-chairs the AIA Minnesota Committee on the Environment (COTE).

Simona was instrumental in the Living Building Challenge Petal Certification of MSR Design’s new downtown Minneapolis headquarters, which achieved the materials, beauty, and equity petals. The project incorporated more than 114 Red List Free materials and achieved a 28 percent reduction of its embodied carbon footprint by using salvaged materials. She also led the development of guidelines around transparency, sustainability, and health for the firm’s materials library, including training materials for staff and external sales reps.

We sat down with Simona to learn why materials have been a focus of her career and to get her perspective on the green building industry today.

What sparked your passion about healthier materials? Was there an “aha” moment or a time that something just clicked?

I was that kid who won a prize for designing the elementary school recycling banner, so I guess I’ve cared about materials for a long time. But my interest in building materials was piqued in architecture school, when we were challenged to create a new ecolabel. Faced with inventing a way to compare one material to another in terms of sustainability, I realized how mind-blowingly complex of a task that was. How do you make the criteria objective? How do you compare products across categories? How do you measure health – is it just by the list of ingredients, or do you include research on health outcomes factoring exposure and risk (and if so, what research even exists)? How do you stack human health and other metrics against each other and choose which factor outweighs the other? How do you account for performance and durability? The questions were endless and led to more questions, which I found complex and intriguing. In other topic areas like water and energy in buildings, the goal seemed straightforward (at least on the surface). Use less energy, and make it cleaner. Use less water, and make it cleaner. But with materials, the number of variables were infinite. We had to think about balancing not just toxicity to people and embodied carbon, but also harvesting of raw materials, ethical manufacturing, and what to do with all that stuff at the end of its useful life.

I ended up writing my MS thesis on methods for assessing sustainability at the level of the manufacturer, as opposed to focusing solely on individual products which change so frequently. I was really just trying to find a system map at a higher level, and make the big, shifting world of materials more manageable in my head. I still use some of what I learned during that project as indicators of whether a building product manufacturer is serious about human health and sustainability, or just greenwashing. But sometimes they are greenwashing because they don’t know any better, and they are on their way to improving. So you can’t just write off smaller companies who don’t yet have all the documentation. It’s a learning process for them as well.

At MSR Design, the conversation about healthy materials had already started when I joined to work on The Rose, a Living Building-inspired affordable housing development in Minneapolis. My colleagues Rhys MacPherson, Paul Mellblom, and Rachelle Schoessler-Lynn were leading the conversation about why we should, and how we could, avoid vinyl and other chemicals on The Rose and on other projects across the firm. Over the next couple years we held a number of all-staff discussions and training sessions on healthy materials. Many staff members, from seasoned designers to interns, became interested in the question of how we could do better while still delivering a beautiful aesthetic and the best functionality for our clients. By the time we were ready to start designing our new studio, healthy materials as a concept had had enough time to become embedded in the culture

Tell us about your project to build the new MSR studio. Why was it important to prioritize healthy materials for this project? What went into your process?

When we knew we were moving, we held an all-staff discussion to debate frameworks for certification. We considered LEED, WELL, Fitwell, and Living Building Challenge Petal Certification. In the end, LBC won, because the Materials Petal was so ambitious, prioritizing not only human health through the use of Red List Free products, but also environmental health and other butterfly-effect impacts of resource harvesting and global warming potential and waste. At the same time, the LBC path included an emphasis on equity, as well as using the project as a tool to educate and inspire others. We found the holistic approach inspiring, and appreciated the challenge (most days).

It was important to prioritize healthy materials because we knew our staff cared about living out our values around healthy indoor environments. I think the team will agree that meeting the Red List requirement was difficult. It took time to develop a workflow for gathering the documentation. But it also gave us the opportunity to rethink the way we approach materials from the start of projects. Instead of trying to weed out all the “bad” chemistry, we found it was actually easier to start from scratch and build up a list of materials we knew were likely to comply with the requirement. It ended up being simpler, mostly natural materials, which we used as the palette for our space.

How do you consider low embodied carbon versus health in product selection?

Non-toxic materials and low embodied carbon are two lenses on a singular problem, which is planetary health. Human health is a subcategory of planetary health, since we’re part of the planet and made of its stuff. When indoor and outdoor environments, and plant and animal and human bodies, are polluted by toxic substances, both from human-made toxins and an overabundance of greenhouse gasses, the global ecosystem suffers and humans suffer within it. We are nature. What’s interesting is, younger, upcoming professionals and design students seem to understand this intuitively. They don’t even need to be told that human and global environmental health go hand in hand. So I think as an industry, we just need to accept the interplay of embodied carbon and human health as a foregone conclusion and get straight to the nitty-gritty of what materials we use and how those materials are grown, produced, manufactured and delivered.

That said, we also need to get serious about the data used to back up carbon and health claims. We need transparent, standardized reporting from manufacturers, including making sure the scope of every life cycle assessment (LCA) takes all the impact categories of the AIA Materials Pledge into account. I think petroleum-based building materials are going to be a battleground for a while to come. The low purchase price and saturation in the market make plastics seem like an easy choice for all kinds of different finishes and performance layers in buildings. It is possible to make them somewhat healthier for end-users by being careful to avoid certain additives. But that leaves a massive loophole; the impacts of production and waste on planetary health. I think there’s an opportunity for data to drive a new understanding here. If we can start seeing standardized collection and data crunching of environmental product declaration (EPD) data from different product sectors, we might be able to correlate carbon from building products more directly to regional health impacts of the production of those chemistries. This would help close loopholes that allow the incredible health impact of high global warming potential (GWP) emissions to stay hidden in the shadows

How have you used your knowledge to help move your clients toward healthier materials? What has been most successful?

I think some of my most successful work has been in addressing priorities and processes in our workflow. I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard people say they just wish there was a single, simple database of all the great products. There are ever-improving databases out there, but people always want something else that is missing, so the problem hasn’t been solved. I think the missing piece is a deeper understanding of the principles of product categories, such as knowing what different types–not brands, but general types–of insulation or countertop materials are made of, and where they come from. This level of knowledge, over time, becomes a kind of intuition one uses to filter the world of products even as new things constantly appear in your inbox or your lunch and learns. When you understand the principles, and don’t just rely on a database to provide a solution, it also gets easier to speak knowledgeably and make solid recommendations to clients.

On project work, I have the best luck when I’m upfront about why we need to consider material health alongside cost. You have to tailor your message to the audience, for example, some clients are most receptive to the idea of improving their impact on the world, whereas for others, the message that hits home is one of directly affecting their health or the health of people they care about

How has Habitable’s InformedTM building product research been helpful or influential?

I love InformedTMand recommend it to designers all the time, and clients too. The information is organized in terms of product categories as opposed to brand names or labels, so it aligns with the level of learning that I think is most beneficial to becoming smarter in practice. We used the sample specs to rewrite our paint specifications in 2021. We’ve also heard great lectures from Habitable research team members over the years that have left an impact on our staff.

What advice do you have for other AEC leaders? Are there processes or approaches you would recommend? Where would you recommend a newcomer to healthier materials start?

For designers, I recommend signing the AIA Materials Pledge and studying the categories. The Pledge is a great framework – if you address each of the Pledge categories in some way, you know you’re hitting the right bases. If you can, allot some time to staff education and discussion. I recommend the Living Building Challenge Materials Petal as a particularly inspiring framework for education and good discussion, because it is based on absolute goals, instead of relative improvement. The COTE Super Spreadsheet (downloadable on the AIA website) is a good starting point for addressing materials issues in an applied manner on projects.

At MSR Design, our internal education efforts led to the development of our Material Library Entry Criteria. If others want to design similar criteria for their libraries, they are welcome to copy ours outright or modify as needed: www.msrdesign.com/generative-impacts.

The more we as designers align in our message to manufacturers about health and carbon, the easier it becomes for them to stay in business while giving us what we want

What are you most excited about right now?

I’m excited about natural and biobased materials. On the high-tech side, there is so much opportunity for new materials to be developed, especially bio-based polymers. On the other hand, there is a new straw bale project that is being built in Minneapolis. It’s low tech in comparison to the latest research in biomaterials, and yet it combines healthy, natural materials seamlessly with low carbon construction. The team is using Passive House building science principles to build a durable system, which they will test with sensors in the walls over the next few years. I really resonate with the idea that we can build a sustainable future with natural materials in both high- and low-tech ways

What do you want other people to know?

We, as an industry, are practicing architecture and construction in an era where buildings are made of hybrid material systems so complex, we hardly know what’s in them or why they work. I think we architects can perhaps find evidence of the Vitruvian virtues of utilitas (utility) and venustas (beauty) in the work we produce, but somewhere as a profession, I think we have let go of the firmitas (stability). Not in the sense of solid structure, but in the sense of owning materiality and material knowledge as a critical aspect of an architect’s role. We have become accustomed to accepting a level of vagueness about assemblies and their tons of little components, and leaving the details to the product manufacturer. I think understanding materials deeply is about reclaiming this knowledge, and a piece of architecture we have lost

Thank you to Simona and MSR design for being leaders in healthier materials! To learn more about the MSR headquarters project, check out this case study. You can also learn more about MSR’s commitment to sustainable design and download their Sustainable Materials Action Packet on their website. Follow this link to learn more about InformedTM, product guidance which Simona mentions influencing her practice.

What do building materials have to do with social justice? Learn more in this article by Diana Alley, Avideh Haghighi, and Lona Rerickat at ZGF Architects.

The Louisville Charter for Safer Chemicals, endorsed by over 100 organizations, confronts the chemical industry’s role in the climate crisis and provides guidance for advancing environmental justice in communities disproportionately affected by harmful chemical exposure.

Healthy Building Network (HBN) and 100+ organizations stand united behind the new Louisville Charter for Safer Chemicals, a roadmap for transforming the chemical industry to one that is no longer a source of greenhouse gas emissions and significant human and environmental health harms.

The goal of the updated charter is to protect human health and the environment and achieve environmental justice for all who experience disproportionate impacts from cumulative chemical sources, including people of color, low-income people, Tribes and Native/Indigenous communities, women, children, and farmworkers.

The original Charter was created in 2004; at that time, HBN joined a broad coalition of grassroots, labor, health, and environmental justice groups in an extensive process initiated by community organizations in Louisville, KY. Louisville’s “Rubbertown” area hosted 11 industrial facilities that released millions of pounds of toxic air emissions every year. The Charter was named in honor of this city and all of the communities across the nation exposed to toxic chemical contamination—starting with the people who are harmed first and worst. We participated in the 2021 update process, supporting the efforts of the most heavily impacted communities to more explicitly address the chemical industry’s massive contribution to the climate crisis, and the need to advance environmental justice in communities who are disproportionately impacted.

The Louisville Charter is a unifying guide for everyone working to ensure that toxic chemicals are no longer a source of harm, from local and national policy-makers and labor organizers, to health care workers and concerned community members, to committed leaders in the building industry. It is meant to be versatile and used in a wide variety of contexts for one overarching purpose: to overhaul chemical policies in favor of safety, health, equity, and justice, and avoid false solutions that simply shift harms to other people and places.

HBN is proud to be a signatory of the Charter and join this diverse and intersectional community of partners demanding urgent action to protect, strengthen, and restore our most vulnerable communities.

To learn more about the Louisville Charter for Safer Chemicals and its ten platform planks, visit www.louisvillecharter.org.

“When I came here, my unit was on the brink of falling apart. We had so many problems; the carpets were incredibly old, and turning the AC on was like having a helicopter inside the house.”

These are the words of Vanessa del Campo. She was born and raised in Mexico and like many other people, she moved to the United States searching for safer and better living conditions. She now lives in Minnesota and rents a small unit in a multifamily apartment building located in one of the areas designated by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) as of Environmental Justice concern. Her experience as a tenant is filled with stories of unjust evictions, health concerns, and constant battles with unlawful landlords that neglected her right to even the most basic human living conditions.

Fortunately for Vanessa and other neighbors in her building, she received support from a community-based organization, Renters United for Justice (abbreviated IX from its name in Spanish), that helped them organize and mobilize to reclaim desperately needed services to maintain their health and wellbeing. What began as an organized effort to request new windows for a handful of apartment units turned into an exhausting but successful journey to purchase the run-down complex of apartment buildings from their landlord and secure a loan to renovate all the apartments.

It’s easy to get lost in Vanessa’s excitement as she talks about this newfound opportunity. She mentioned that her baby had a tough time learning to crawl because it was too dangerous to place her on the ground due to rats and cockroaches often running past her. At the same time, it is also easy to forget that in addition to being a mother and having a demanding job, she now has to fulfill the role of a building co-owner as a leading member of the newly formed residents’ collective (A Sky Without Limits).

With so much work going into buying and renovating the apartment complex, the residents had little time to think about the chemical safety of their chosen building materials. That’s where HBN came in. In 2021 the MPCA awarded IX and Healthy Building Network a grant to work together to reduce toxic chemical exposures among children, pregnant individuals, employees, and communities who are disproportionately impacted by harmful chemicals used in common products.

One example of toxic chemicals in homes are phthalates, or orthophthalates, which are chemicals that help make plastics flexible. They can also impact the proper development of children. These chemicals are banned in children’s toys in the U.S., and The Minnesota Department of Health in partnership with MPCA named phthalates as “Priority Chemicals” as part of the 2017 Toxic-Free Kids Act. While many manufacturers have phased out hazardous phthalate plasticizers, existing vinyl flooring, especially those installed 2015 and earlier, likely contain these potential developmental toxicants. This translates to dozens of pounds of these hazardous chemicals in the floor of a single apartment unit. As these chemicals are released from products, they deposit in dust, which can be inhaled or ingested by residents – particularly young children who are crawling on floors and often place their hands in their mouths.

“Honestly, we never stopped to think about how harmful [building] materials could be.” Vanessa said. “It was just regrettable to see how we were living. We understand that the new materials that are going into our buildings today may not be the healthiest. Today, we realize it is important to think about how we want to live in our homes, to imagine the quality of life we want in our buildings, in our community.”

Over the coming year, HBN will work with IX and the residents’ collective to evaluate the materials used in their ongoing renovation process and provide recommendations to improve material selection. We will also develop resources tailored to residents to enhance their understanding of how the surrounding environment influences their health. To extend the impact of this work, we will create and share a set of best practices that property managers and tenant organizations can use to advocate for healthier materials in the communities they live in and properties they manage.

“Our collaboration with HBN is timely. By working together with the property managers, we can raise their awareness about how their work impacts our health and help change how they select materials,” Vanessa said.

At Healthy Building Network, we are grateful for the opportunity to work with IX and local leaders like Vanessa through the MPCA grant that makes this collaboration possible. We call on public agencies, foundations, and private investors to fund initiatives that seek to dismantle health inequities through direct investment in the communities disproportionately impacted by environmental injustice, especially related to toxic chemical exposures. We look forward to sharing with you the lessons, stories, and resources that come out of this collaboration.

To learn more about selecting healthier products, visit our Informed™ website, which includes a wide range of resources and tools to help you find healthier material options.

Un inquilino clama por viviendas más seguras y saludables

“Cuando llegué aquí, mi apartamento estaba a punto de desmoronarse. Tuvimos muchos problemas; las alfombras eran increíblemente viejas y encender el aire acondicionado era como tener un helicóptero dentro de la casa”. Estas son las palabras de Vanessa del Campo.

Vanessa nació y creció en México, y como muchas otras personas, se mudó a los Estados Unidos en busca de mejores condiciones de vida. Ahora vive en Minnesota y alquila un apartamento en un edificio multifamiliar ubicado en una de las áreas designadas por la Agencia de Control de Contaminación de Minnesota (MPCA) como de interés de Justicia Ambiental. Su experiencia como inquilina está marcada con historias de desalojos injustos, preocupaciones de salud, y batallas constantes con propietarios que negaron su derecho a incluso las condiciones más básicas de vida.

Afortunadamente para Vanessa y otros vecinos en su edificio, ella recibió el apoyo de Inquilinos Unidos por Justicia (IX), una organización comunitaria que les ayudó a organizarse y movilizarse para recuperar los servicios que desesperadamente necesitaban para mantener su salud y bienestar. Lo que comenzó como un esfuerzo organizado para solicitar nuevas ventanas para un pequeño número de apartamentos, se convirtió en una larga pero exitosa tarea para comprar el destartalado complejo de apartamentos y asegurar un préstamo para renovar todas sus unidades.

“Pasamos por muchos litigios con el propietario porque no estaba haciendo las reparaciones que necesitábamos y no quería vendernos los edificios. El año pasado, cuando llegó la pandemia, finalmente obtuvimos la oportunidad de comprar el edificio. Fue un momento feliz y difícil porque estábamos aterrorizados de enfermarnos [con el virus], pero logramos organizarnos y apoyarnos unos a otros. Hoy estamos trabajando con una nueva empresa de administración de propiedades y el banco para instalar alfombras, pisos, techos, ventanas, hornos, refrigeradores y baños nuevos. Estamos haciendo una profunda renovación para llevar todos los apartamentos a un estado que es mucho, mucho mejor que el que teníamos”.

Es fácil dejarse llevar por la emoción de Vanessa mientras habla de esta nueva oportunidad. Ella mencionó que su bebé tuvo dificultades para aprender a gatear porque era demasiado peligroso colocarle en el suelo debido a las ratas y cucarachas que a menudo rondaban la casa. Al mismo tiempo, también es fácil olvidar que además de ser madre y tener un trabajo exigente, ahora tiene que cumplir el rol de copropietaria de un edificio como miembro principal de un recién formado colectivo de residentes (Un Cielo Sin Límites).

Con tanto trabajo invertido en la compra y renovación del complejo de apartamentos, los residentes tuvieron poco tiempo para pensar en la seguridad química de los materiales de construcción que fueron utilizados en sus apartamentos. Ahí es donde entra Healthy Building Network (HBN, o, La Red de Edificios Saludables). A principios de este año, MPCA otorgó a IX y HBN una subvención para reducir la exposición a sustancias químicas tóxicas entre los niños, las personas embarazadas, los empleados y las comunidades que se ven afectadas de manera desproporcionada por sustancias químicas nocivas utilizadas en productos comunes.

Un ejemplo de sustancias químicas tóxicas en los hogares son los ftalatos u ortoftalatos, que son sustancias químicas utilizadas para ayudar a dar flexibilizar a los plásticos. Estas sustancias también pueden afectar el desarrollo adecuado de los niños. Estos productos químicos están prohibidos en los juguetes de los niños en los EE. UU. El Departamento de Salud de Minnesota, en asociación con MPCA, nombró a los ftalatos como “productos químicos prioritarios” como parte de la Ley de Niños Libres de Tóxicos de 2017. Si bien muchos fabricantes han eliminado los plastificantes de ftalato, estos químicos están presentes en los pisos de vinilo existentes, especialmente los instalados antes de 2016. Esto se traduce en docenas de libras de estos químicos peligrosos en el piso de una sola unidad de apartamento. A medida que estos productos químicos se liberan de los productos, se depositan en el polvo que los residentes pueden inhalar o ingerir, afectando especialmente a los niños pequeños que gatean por el suelo y a menudo se llevan las manos a la boca.

“Honestamente, nunca nos detuvimos a pensar en lo dañino que podrían ser los materiales [de construcción]”. Dijo Vanessa. “Fue lamentable ver cómo vivíamos. Entendemos que los materiales que se utilizan en nuestros edificios hoy en día pueden no ser los más saludables. Hoy nos damos cuenta de que es importante pensar en cómo queremos vivir en nuestros hogares, imaginar la calidad de vida que queremos en nuestros edificios, en nuestra comunidad”.

Durante el próximo año, HBN trabajará con IX y el colectivo de residentes para evaluar los materiales utilizados en su proceso de renovación y brindar recomendaciones para mejorar la selección de materiales. También desarrollaremos recursos para ayudar a los residentes a entender cómo el entorno circundante influye en su salud. Para extender el impacto de este trabajo, crearemos y compartiremos un conjunto de mejores prácticas para que los administradores de propiedades y las organizaciones de inquilinos puedan abogar por utilizar materiales más saludables en las comunidades en las que viven y en las propiedades que administran.

“Nuestra colaboración con HBN es oportuna. Al trabajar junto con los administradores de propiedades, podemos aumentar su conciencia sobre cómo su trabajo impacta nuestra salud y ayudar a cambiar la forma en que seleccionan los materiales”, dijo Vanessa.

En Healthy Building Network, estamos agradecidos por la oportunidad de trabajar con IX y líderes locales como Vanessa a través de la subvención otorgada por MPCA que hace posible esta colaboración. Hacemos un llamado a las agencias públicas, fundaciones e inversionistas privados para que financien iniciativas que busquen desmantelar las inequidades en salud a través de inversión en las comunidades impactadas de manera desproporcionada por la injusticia ambiental, especialmente relacionada con la exposición a sustancias químicas tóxicas. Esperamos pronto poder compartir con ustedes las lecciones, historias y recursos que surgen de esta colaboración.

Dr. Ami Zota, Associate Professor at the Department of Environmental & Occupational Health at the George Washington University (GWU) Milken Institute School of Public Health, created a platform to amplify underrepresented voices in science and environmental health. She launched her vision, Agents of Change, in 2019 with its first cohort of changemakers.

The high-achieving crew included Dr. MyDzung Chu, a first-generation Vietnamese-American, environmental epidemiologist, new mother, and postdoctoral scientist at the GWU Milken Institute School of Public Health. MyDzung is invested in understanding social determinants of health and environmental exposures within the home, workplace, and neighborhood contexts. Her current research investigates the impact of federal housing assistance on residential environmental exposures for low-income communities.

In her Agents of Change blog, Why Housing Security is Key to Environmental Justice, MyDzung examines the intersection of housing, racism, and environmental justice, and its effects on population health. She challenges us: “It is time for the environmental health community to step up and be at the forefront of addressing housing insecurity.”

MyDzung is practicing what she preaches – and blazing a trail while doing it. In her local community, MyDzung organizes with residents and non-profit organizations for affordable housing, equitable development, and anti-displacement policies. Her dissertation research examined socio-contextual drivers of disparities in indoor and ambient air pollution and poor housing quality for low-income, immigrant, and Black and Brown households. In a study published in Environmental Research, MyDzung and colleagues found that renters in multifamily housing were exposed to higher levels of fine particulate matter indoors that homeowner households, due to a combination of building factors and source activities that may be modifiable, such as building density, air exchange, cooking, and smoking.

MyDzung has a PhD in Population Health Sciences from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, a MSPH in Environmental-Occupational Health and Epidemiology from Emory University, and a BA in Neuroscience from Smith College.

To keep up to date with MyDzung’s research and impacts, you can follow her on Twitter or LinkedIn. And, click this link to learn more about her colleagues at Agents of Change. Thanks, MyDzung, for your leadership and courage to advance real change.

Plastic is a ubiquitous part of our everyday lives, and its global production is expected to more than triple between now and 2050. According to industry projections, we will create more plastics in the next 25 years than have been produced in the history of the world so far.

The building and construction industry is the second largest use sector for plastics after packaging.1 From water infrastructure to roofing membranes, carpet tiles to resilient flooring, and insulation to interior paints, plastics are ubiquitous in the built environment.

These plastic materials are made from oil and gas. And, due to energy efficiency improvements, for example–in building operations and transportation–the production and use of plastics is predicted to soon be the largest driver of world oil demand.2

Plastic building products are often marketed in ways that give the illusion of progress toward an ill-defined future state of plastics sustainability. For the past 20 years, much of that marketing has focused on recycling. But for a variety of reasons, these programs have failed.

A recent study from the University of Michigan makes it clear that the scale of post-consumer plastics recycling in the US is dismal.3 Only about 8% of plastic is recycled, and virtually all of that is beverage containers. Further, most of the recyclate is downcycled into products of lower quality and value that themselves are not recyclable. For plastic building materials, the numbers are more dismal still. For example, carpet, which claims to have one of the more advanced recycling programs, is recycled at only a 5% rate, and only 0.45% of discarded carpet is recycled into new carpet. The rest is downcycled into other materials, which means their next go-around these materials are destined to be landfilled or burned.4 After 20 years of recycling hype, post-consumer recycling of plastic building materials into products of greater or equal value is essentially non-existent, and therefore incompatible with a circular economy.

Why isn’t plastic from building materials recycled?

Additives (which may be toxic), fillers, adhesives used in installation, and products made with multiple layers of different types of materials all make recycling of plastic building materials technically difficult. Lack of infrastructure to collect, sort, and recycle these materials contributes to the challenge of recycling building materials into high-value, safe new materials.

Manufacturers have continued to invest in products that are technically challenging to reuse or recycle – initially cheaper due to existing infrastructure – instead of innovating in new, circular-focused solutions. Additionally, their investment in plastics recycling has been paltry. In 2019 BASF, Dow, ExxonMobill, Shell and numerous other manufacturers formed the Alliance to End Plastic Waste (AEPW) and pledged to invest $1.5 billion over the next five years into research and development of plastic waste management technologies. Compare that to the over $180 billion invested by these same firms in new plastic manufacturing facilities since 2010.5

Globally, regulations that discourage or ban landfilling of plastics have, unfortunately, not led to more recycling overall. Instead, burning takes the place of landfilling as the eventual end of life for most plastics.

Confusing rhetoric around plastic end of life options can make this story seem more complicated than it is.6

- “incineration” or “waste to energy” burns plastic for energy.

- “Plastic-to-fuel” or “gasification” or “pyrolysis” generates fuel. This output is rarely used for anything but burning due to the additional processing required to use for any other purpose.

- “Chemical recycling” could, in theory, lead to new plastic products. This technology is unproven and currently not a scalable solution. The outputs are often burned due to low quality.

Plastic waste burning, regardless of the euphemism employed, is a well established environmental health and justice concern.

Burning plastics creates global pollution and has environmental justice impacts.

In its exhaustive 2019 report, the independent, nonprofit Center for International Environmental Law (CEIL) documents how burning plastic wastes increases unhealthy toxic exposures at every stage of the process. Increased truck traffic elevates air pollution, as do the emissions from the burner itself. Burned plastic produces toxic ash and residue at approximately one fifth the volume of the original waste, creating new disposal challenges and new vectors of exposure to additional communities that receive these wastes.7

In the US, eight out of every 10 solid waste incinerators are located in low-income neighborhoods and/or communities of color.8 This means, in some cases, the same communities that are disproportionately burdened with the pollution and toxic chemical releases related to the manufacture of virgin plastics are again burdened with its carbon and chemical releases when it is inevitably burned at the end of its life.

The issue is global in scale. A recent report by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) found that “plastic waste incineration has resulted in disproportionately dangerous impacts in Global South countries and communities.” The Global Alliance for Incineration Alternatives (GAIA), a worldwide alliance of more than 800 groups in over 90 countries, has been working for more than 20 years to defeat efforts to massively expand incineration, especially in the Global South. GAIA members have identified incineration not only as an immediate and significant health threat in their communities, but also a major obstacle to resource conservation, sustainable economic development, and environmental justice.

Where do we go from here?

- Minimize production of virgin plastic. This should be the main focus of any plastic waste reduction plan and part of any comprehensive climate change initiative. Policies banning single use plastics or banning the construction of new plastic production facilities or facility expansions are two example solutions cited by GAIA.9 Less plastic means less waste and less material to incinerate.

- Invest in true circular economy initiatives. These may include, for example: extended producer responsibility programs, materials passports, materials disclosure, elimination of toxic chemical additives, product as a service models, and recycling facilities that support upcycling. By shifting industry investments toward circular economy infrastructure – instead of the nearly $200 billion investments in increased manufacturing and burning capacity – the plastic industry could start to be part of the solution of reducing plastic waste.

- When evaluating the “expense” of recycling and circularity vs business-as-usual, a fair calculation for the latter needs to include all costs associated with the production, use, and end of life impacts of plastics. That “cheap” vinyl floor is no longer so inexpensive when the full costs of global pollution and the health burdens of people of color and low income communities are included in the math. Externalities must be a part of the equation.

What is unquestionable is this: Today our only choices for plastic waste are to burn or landfill most of it. Expanding plastics production and incineration is a conscious decision to perpetuate well documented, fully understood inequity and injustice in our building products supply chain.

The folks at The Story of Stuff cover this in The Story of Plastics, four minute animated short suitable for the whole family. Comedian John Oliver tells the “R-rated” version of the story with impeccable research and insightful humor in his HBO show Last Week Tonight. It’s worth a look to learn exactly how the plastics industry uses the illusion of recycling to sell ever increasing volumes of plastic. Without manufacturer responsibility and investment, efforts to truly incorporate plastic into a circular economy have little chance of success.

SOURCES

- https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution

- https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/bee4ef3a-8876-4566-98cf-7a130c013805/The_Future_of_Petrochemicals.pdf See page 18, 30.

https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/us-energy-facts/ - https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab9e1e/pdf

- https://carpetrecovery.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CARE-2019-Annual-Report-6-7-20-FINAL-002.pdf

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jan/21/founders-of-plastic-waste-alliance-investing-billions-in-new-plants

- https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/False-solutions_Nov-9-2020.pdf

- https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Plastic-and-Climate-FINAL-2019.pdf

- https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d14dab43967cc000179f3d2/t/5d5c4bea0d59ad00012d220e/1566329840732/CR_GaiaReportFinal_05.21.pdf

- https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/False-solutions_Nov-9-2020.pdf

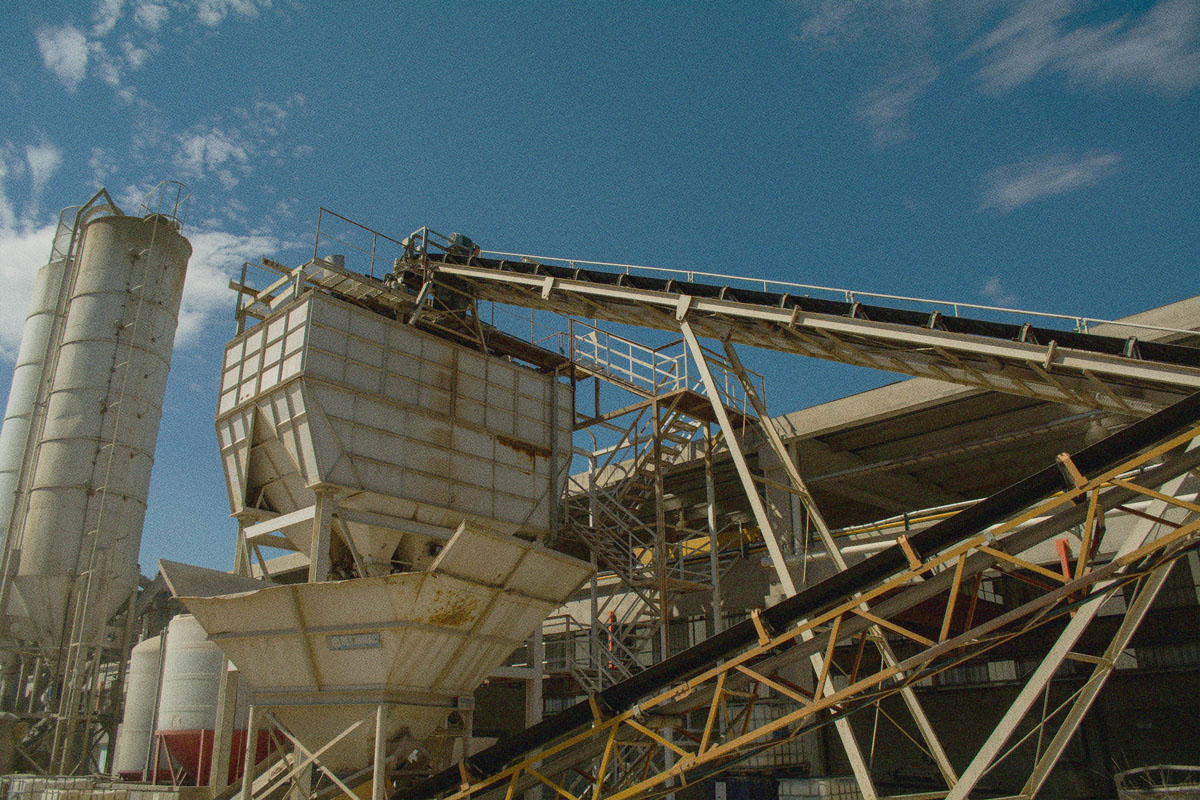

In Louisiana, the factories that make the chemicals and plastics for our building products are built literally upon the bones of African Americans. Plantation fields have been transformed into industrial fortresses.

A Shell Refinery1 sprawls across the former Bruslie and Monroe plantations. Belle Pointe is now the DuPont Pontchartrain Works, among the most toxic air polluters in the state.2 Soon, the Taiwan-based Formosa Plastics Group intends to build a 2400-acre complex of 14 facilities that will transform fracked gas into plastics. It will occupy land that was formerly the Acadia and Buena Vista plantations, and not incidentally, the ancestral burial grounds of local African American residents, some of whom trace their lineage back to people enslaved there.3

Formosa has earned a reputation of being a poor steward of sacred places. Local residents have petitioned the Governor to deny permits for the facility, citing a long list of environmental health violations in its existing Louisiana facilities, including violations of the Clean Air Act every quarter since 2009.4 The scofflaw company was found to have dumped plastic pellets known as “nurdles” into the fragile ecosystem of Lavaca Bay on the Gulf of Mexico for years – leading to a record $50 million settlement with activists in that community in 2019.5

In the Antebellum South, formerly enslaved people often homesteaded on lands that were part of or near the plantations they once worked. They established communities of priceless historical and cultural worth, towns such as Morrisonville, Diamond, Convent, Donaldsonville, and St. James. Donaldsonville, Louisiana, is the town that elected Pierre Caliste Landry, America’s first African American mayor in 1868, just three years after the end of the Civil War. This part of Louisiana holds many layers of complex and deep African American history.

But in the last 75 years, since World War II, these communities have been overrun by petrochemical industry expansion enabled by governments wielding the clout of Jim Crow laws to snuff out any opposition or objection. Towns like Morrisonville and Diamond have been bought up to accommodate plant expansion. Residents have been forced to move out, their history and heritage literally paved over. It wasn’t until 1994 that the River Road African American Museum was established to preserve and present the history of the Black population as distinct from plantation representations of slavery. According to Michael Taylor, Curator of Books, Louisiana State University Libraries: “Only in the last few decades have historians themselves begun to appreciate the complexity of free black communities and their significance to our understanding not just of the past, but also the present.”6

Charting a New Way Forward—Together

Virtually every building product we use today contains a petrochemical component that originates from heavily polluted communities, frequently home to people of color. As the green building movement searches for ways to enhance diversity, inclusion and equity, how might it address the legacies of injustice that are tied to the products and materials we use every day?

Architect, Zena Howard, FAIA, offered insight in her 2019 J. Max Bond Lecture, Planning to Stay, keynoting the National Organization of Minority Architects national conference. Howard, known for her work on the design team for the breathtaking Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, most often works with people in communities whose culture and heritage were “erased” by urban renewal in the 1960’s. In Greenville, North Carolina, she looked to people from the historically African American Downtown Greenville community and Sycamore Hill Missionary Baptist Church Congregation to guide the planning and design process for a new town common and gateway plaza. The goal was not to “replicate” the lost community, but to bring its history and present day aspirations to life in the new design. In Vancouver, British Columbia, the development plan for a neighborhood founded by African Canadian railroad porters included an unprecedented chapter on “reconciliation and cultural redress.” The key to such efforts, according to Howard is co-creation and meaningful collaboration, whose Greek roots, she notes, mean “to labor together.”

How might we labor together to address environmental injustice when evaluating the overall healthfulness and equity of our building materials? The precedent of “insetting” suggests an approach.

Insetting has been pioneered by companies whose supply chains rely upon agricultural communities across the globe. According to Ceres, insetting is “a type of carbon emissions offset, but it’s about much more than sequestering carbon: It’s also about companies building resiliency in their supply chains and restoring the ecosystems on which their growers depend.”

In previous columns, I’ve addressed concerns about the social in industrial communities, e.g., proposals that perpetuate disproportionate pollution impacts when buying offsets rather than addressing emissions from a specific facility. Applying the “insetting” approach we might ask our materials manufacturers—and the communities that are home to the building materials industries—what steps can we take to encourage manufacturers to “labor with” communities seeking environmental justice, such as those along the Mississippi River? Can we, together, resurrect and restore their history, reconcile and redress historical wrongs, and build a healthier future for all?

Black History

Month Readings

To learn more about the history and present day conditions of Cancer Alley, see these excellent articles from The Guardian and Pro Publica: https://www.ehn.org/search/?q=cancer+alley

You can watch to Zena Howard’s J. Max Bond lecture, Planning to Stay, here: https://vimeo.com/378622662

You can learn more about the River Road African American History Museum here: https://africanamericanmuseum.org/

SOURCES

- Terry L. Jones, “Graves of 1,000 Enslaved People Found near Ascension Refinery; Shell, Preservationists to Honor Them | Ascension | Theadvocate.Com,” accessed February 18, 2020, https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/communities/ascension/article_18c62526-2611-11e8-9aec-d71a6bbc9b0c.html.

- Oliver Laughland and Jamiles Lartey, “First Slavery, Then a Chemical Plant and Cancer Deaths: One Town’s Brutal History,” The Guardian, May 6, 2019, sec. US news, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/may/06/cancertown-louisiana-reserve-history-slavery.

- Sharon Lerner, “New Chemical Complex Would Displace Suspected Slave Burial Ground in Louisiana’s ‘Cancer Alley,’” The Intercept (blog), December 18, 2019, https://theintercept.com/2019/12/18/formosa-plastics-louisiana-slave-burial-ground/.

- Louisiana Bucket Brigade, “Sign the Petition,” Change.org, accessed February 25, 2020, https://www.change.org/p/governor-edwards-stop-the-formosa-chemical-plant.

- Stacy Fernández, “Plastic Company Set to Pay $50 Million Settlement in Water Pollution Suit Brought on by Texas Residents,” The Texas Tribune, October 15, 2019, https://www.texastribune.org/2019/10/15/formosa-plastics-pay-50-million-texas-clean-water-act-lawsuit/.

- LSU Libraries, “Free People of Color in Louisiana,” LSU Libraries, accessed February 18, 2020, https://lib.lsu.edu/sites/all/files/sc/fpoc/history.html.

The Global Chemicals Outlook II assesses global trends and progress in managing chemicals and waste to achieve sustainable development goals, with a focus on innovative solutions and policy recommendations.

Equity

Equity Health

Health Pollution

Pollution