Policy Brief + Recommendations

Policy Brief + RecommendationsEarthjustice lays out the pillars of the argument against the oil and gas industry’s push for a petrochemical boom, which threatens to lock in more climate pollution and toxic chemicals in already overburdened low-income and minority communities.

This podcast conversation explores the intersection of climate change and chemical pollution.

Highlighting opportunities to address both crises simultaneously while improving public health, equity, and economic vitality, featuring experts Dr. Elizabeth Sawin and Beverley Thorpe.

The idea of a “plastic building” might bring to mind Barbie DreamHouses or Lego towers, but probably not the real life spaces we occupy every day. However, plastics have a long history of use in construction and are increasingly being used in a wide variety of building products.

What are plastics?

Plastics are synthetic or semi-synthetic materials typically made from fossil fuels and their byproducts.1 Depending on the plastic’s intended use, they may also be combined with a variety of additives such as stabilizers, fillers, reinforcements, plasticizers, colorants, and processing aids, many of which are toxic chemicals that are linked to chronic disease. They are a material of choice in the built environment, however, they come with a host of deeply rooted problems.

Durable plastics are the new “frontier”

As the energy sector shifts away from fossil fuels, the fossil fuel industry has turned toward plastics as a way of maintaining demand for their products.2 An International Energy Report from 2018 showed that petrochemicals, which are used to make plastics, are slated to become the largest driver of global oil demand in the near future.3 Historically, much of the investment has been in single-use plastics, which are increasingly the focus of bans, restrictions, regulations, and product innovation due to their harmful environmental effects.2 To pick up this anticipated slack, petrochemical, fossil fuel, and plastics industries are now pushing to increase their market growth in more durable goods, like building materials.4 The building and construction industry is already the second largest consumer of plastics after packaging.5

Plastics contribute to climate change

Plastics contribute to greenhouse gas emissions at every stage of their lifecycle. Greenhouse gases are released during fossil fuel extraction, transport, feedstock refining, and plastic manufacture, and carbon is released into the atmosphere through degradation and incineration at plastic products’ end of life.6 A 2019 Center for International Environmental Law report concluded that these lifecycle emissions may make it impossible to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees if growth continues as projected.6 Any comprehensive climate change plan must curb the production of plastics.

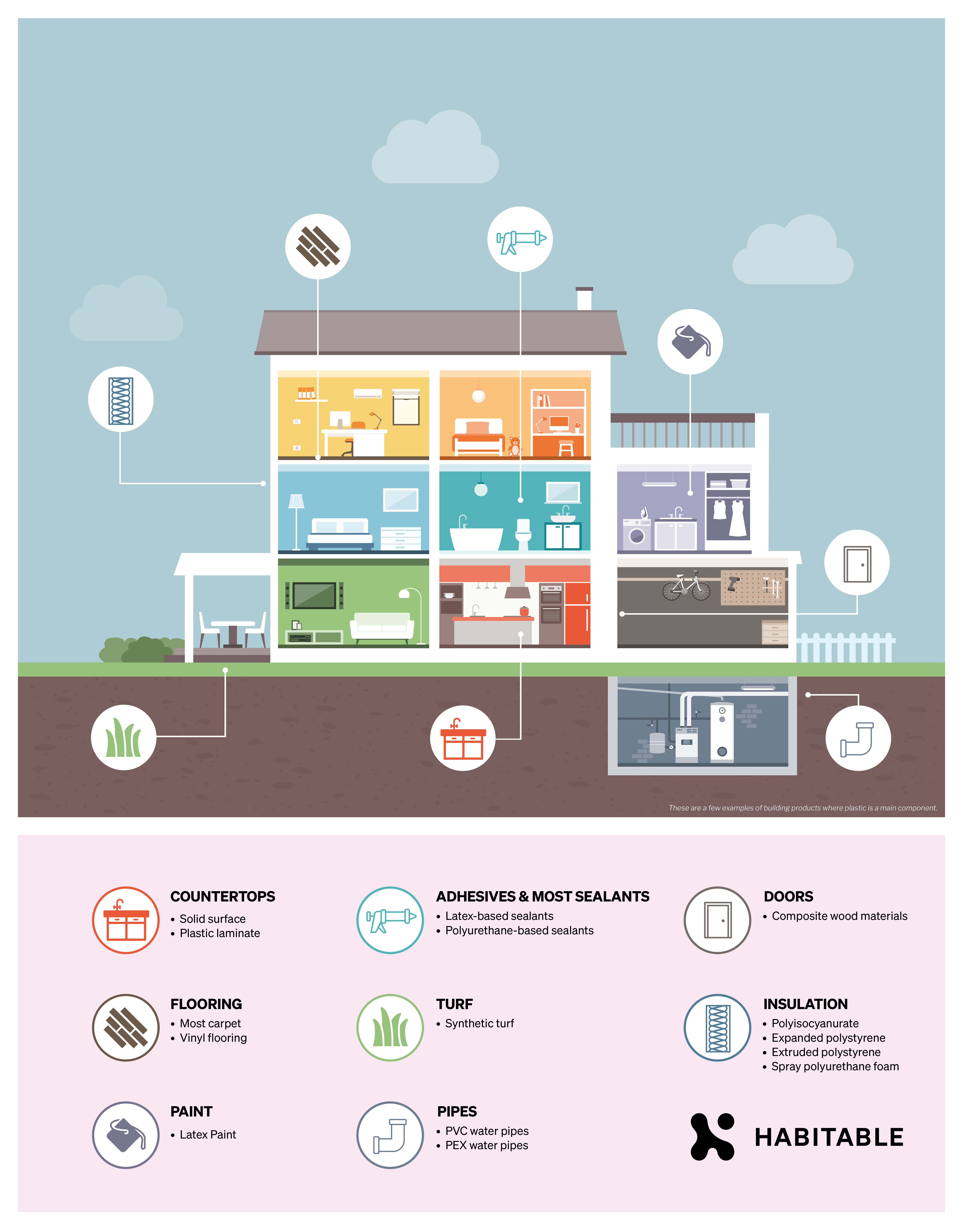

Plastic is ubiquitous in buildings

Maybe you know that vinyl flooring is plastic, but did you know that latex paint is mostly plastic? That many insulation products are plastic? How about carpet? Plastic-containing products can be found in almost every part of a building, from the waterproofing on foundations to roofing materials. See below for an infographic showing just some of the plastic materials in an average home. The products included are not exhaustive, but rather a list of example product types from Habitable’s InformedTM product categories where a main component is plastic. There are many more products that are predominantly made of plastic, and even more that contain smaller amounts of plastic additives or plastic binders.

Our plastic buildings are driving the growth in fossil fuels at the same time as we are diligently working to incorporate clean energy solutions and decarbonize these very same places.

Hidden costs of cheap plastic

Plastic products are often favored due to their “low cost.” This low retail cost is achieved by avoiding and externalizing the costs of fossil fuels and industrial pollution – and their related chronic diseases – throughout the plastics supply chain. These externalized costs are real and paid for by the BIPOC and low-income communities across the nation who are disproportionately burdened with toxic pollution flowing from refineries, chemical manufacturing, and plastics plants. It is fair to say that most of the stories about environmental justice that you have heard can be linked to plastics manufacturing.

Where is the plastic in my building?

With the building and construction industries anticipating growth over the next several years,7 commensurate growth is to be expected in their use of plastics. Indeed, market trends and projections show a steady increase in polyvinyl chloride (aka vinyl), polystyrene, polyethylene, polyurethanes, and other plastics used in building materials.8

It is, of course, unrealistic to avoid all plastic in building materials at this time, but there are steps we can take to reduce plastic waste, decrease toxic chemical use, and curb the demand for fossil fuels.

Select Better: Avoid worst-in-class plastics where possible.

- Where product performance and chemical hazards are similar or better, non-plastic products are preferred.

- Not all plastic products are the same when it comes to impacts. Where plastic products are needed, avoid halogenated plastics or plastics reliant on halogenated chemistry during production – such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC, also known as vinyl) and epoxy-based materials.

- Where plastic products are needed, avoiding virgin plastic materials reduces demand for oil and gas extraction and ultimately mitigates harmful end of life scenarios for the plastic waste such as incineration or landfilling.

Prioritize Transparency: Prefer products that provide transparency

- Disclosure of product content including the type of plastic used and any potential additives will allow for healthier materials choices and better material end-of-life planning.

- In the case of products containing recycled plastics, disclosure of where the recycled content originated and any additives that may be present is crucial in selecting healthier products.

Aim for Circularity: Select products designed for recycling.

- Where possible, incorporating recyclable building materials in ways that allow for end-of-life recycling is preferred.

- Prefer products with “take back” programs. Because true plastics recycling rates are abysmal, the most promising recycling programs are those in which manufacturers retain responsibility for their products and provide recycling options.

- Prefer products that are made with high levels of recycled content that has been screened to avoid toxic tag-alongs and, equally as important, contact manufacturers to recycle any existing product.

With all of these plastic products, our buildings may seem increasingly like Barbie’s DreamHouse and a climate nightmare, but as specifiers, designers, architects, contractors, and owners we can do much to control what products end up in our projects. Starting with the recommendations above, we have the power to influence demand for better and safer materials. In the case of plastics, choosing better materials can lead to less reliance on fossil fuels, fewer greenhouse gas emissions, a decrease in toxic chemical use, and a win for our changing climate.

SOURCES

- For the purposes of this article we are including any synthetic polymer in our definition of a plastic, including thermoplastic, thermoset, and elastomeric polymeric materials.

- Ciel, 2018:

https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Fueling-Plastics-Untested-Assumptions-and-Unanswered-Questions-in-the-Plastics-Boom.pdf - IEA, 2018: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/bee4ef3a-8876-4566-98cf-7a130c013805/The_Future_of_Petrochemicals.pdf

- Plastics Industry Association, 2016:

https://www.plasticsindustry.org/article/growing-role-plastics-construction-and-building - UNEP, 2021:

https://www.unep.org/resources/report/neglected-environmental-justice-impacts-marine-litter-and-plastic-pollution - CIEL, 2019:

https://www.ciel.org/plasticandclimate/ - BusinessWire, 2021:

https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210111005587/en/Global-Construction-Industry-Report-2021-10.5-Trillion-Growth-Opportunities-by-2023—ResearchAndMarkets.com - Grandview Research, 2018:

https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/building-construction-plastics-market

This report discusses how President Biden’s Executive Orders need to go further than examining energy sources to combat the climate crisis, emphasizing the need for the chemical industry to adapt and innovate, considering its significant impact on greenhouse gas emissions and environmental health.

The Future of Petrochemicals report explores the role of the petrochemical sector in the global energy system and its increasing significance for energy security and the environment, highlighting the need for attention from policymakers.

Climate Change

Climate Change Pollution

Pollution