READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

This report discusses how President Biden’s Executive Orders need to go further than examining energy sources to combat the climate crisis, emphasizing the need for the chemical industry to adapt and innovate, considering its significant impact on greenhouse gas emissions and environmental health.

Health Care Without Harm Europe advocates for the complete elimination of PVC due to its environmental impact, urging policymakers to develop a strategy for its phase-out in Europe.

If we are to have any chance of addressing the global plastics crisis, Polyvinyl Chloride plastic (PVC) also known as vinyl, has got to go.

It cannot be produced sustainably or equitably. It cannot be “optimized.” It cannot be recycled. It will never find a place in a circular economy, and it makes it harder to achieve circularity with other materials, including other plastics.

There are three reasons for this: technical, economic, and behavioral. The inherent qualities of PVC and its cousin, CPVC, make it among the most technologically challenging plastics to recycle. Like most plastics, PVC is made with fossil fuel feedstocks. Unlike other plastics, PVC/vinyl also contains substantial amounts of chlorine, upwards of 40%. This is the C in PVC, and this chlorine content adds an additional layer of negative impacts to the earth and its people, social inequity, and an impediment to recycling that cannot be overcome. Recyclers consider it a contaminant to other plastic feedstock streams.1 It mucks up the machines and the already perilous economics of plastics recycling.

There is an emerging global consensus on this point, albeit euphemistically stated. The Ellen MacArthur New Plastics Economy Project consists of representatives from the world’s largest plastic makers and users, along with governments, academics, and NGOs. In 2017 it reached the conclusion that PVC was an “uncommon” plastic that was unlikely to be recycled and should be avoided in favor of other more recyclable packaging materials.2 “Uncommon” in the diplomatic parlance of international multistakeholder initiatives means unrecyclable. The project also took note of the many toxic emissions associated with PVC production.

That’s not surprising since after 30 years of hollow promises and pilot projects doomed to fail, virtually no post-consumer PVC is recycled.3 Conversely, leading brands with forward-looking materials policies such such as Nike, Apple, and Google have prioritized PVC phase outs.4

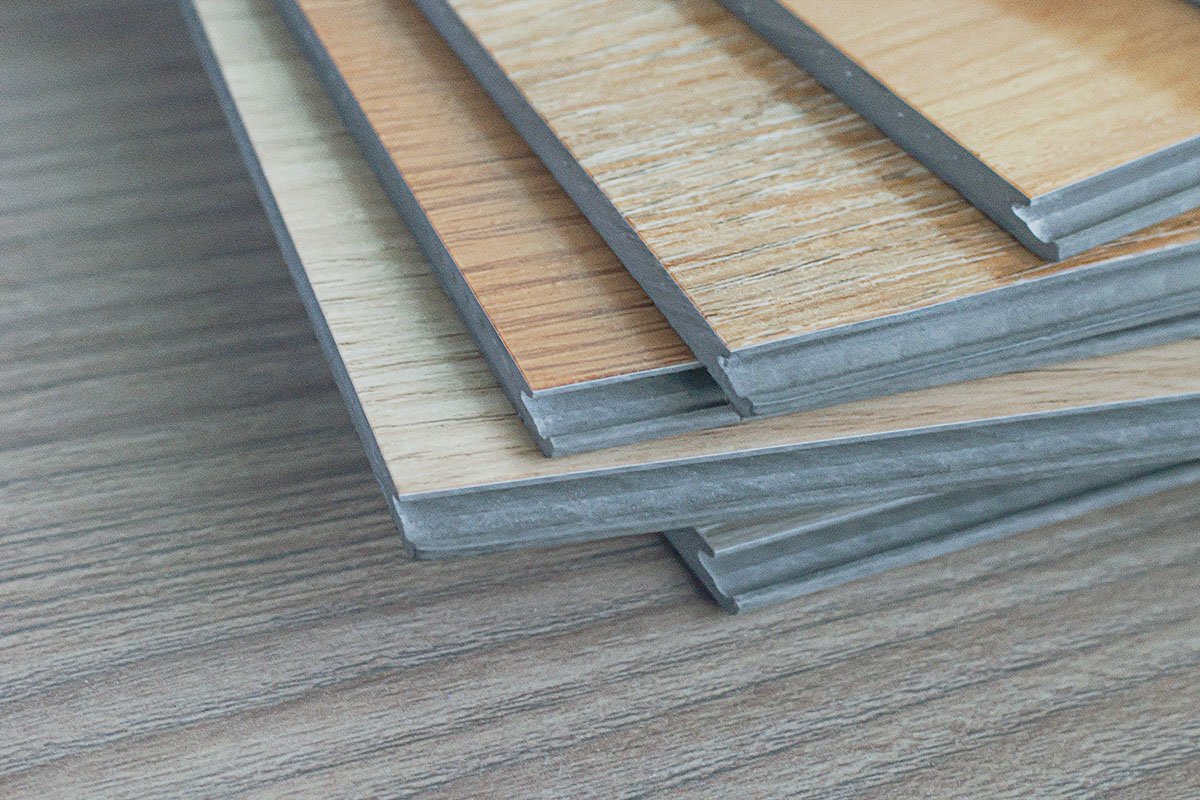

But in the building industry, PVC rages on. Virgin vinyl LVT flooring is the fastest growing product in the flooring sector. So much so that in 2017 sustainability leader Interface introduced a new product line of virgin vinyl LVT, despite forecasting just one year before that by 2020 the company would “source 95 percent of its materials from recycled or biobased resources.”5

The current flooring market demands the impossible – aesthetic qualities and durability at a price unmatchable by non-vinyl floor coverings. A price that is unmatchable because at every stage of vinyl production, the societal costs of its poisonous environmental health consequences are externalized, subsidized, paid for by the people who live in communities that have become virtual poster children for environmental injustice and oppression. Places like Mossville, LA; Freeport, TX; and the Xinjiang Province in China, home to the oppressed Uighur population. As we detail in our exhaustive Chlorine and Building Materials report, the unique chlorine component of PVC plastic contributes to a range of toxic pollution problems starting with the fact that chlorine production relies upon either mercury-, asbestos-, or PFAS-based processes. This is in addition to the onerous environmental health burdens of petrochemical processing that burden all plastics.

It is true that all plastics contribute to environmental injustices. Virtually all plastics are made from fossil fuel feedstocks, and all plastics share abysmally low recovery and cycling rates. Still, independent experts agree that some plastics are worse than others, and PVC is among the worst.6 Additionally, most uses of PVC have readily available alternatives or solutions that are within reach. Certainly there are non-PVC alternatives for flooring. What can’t be beat is the cost – that is, the low purchase price at the point of sale, subsidized by the sacrifices we ignore in the communities where the plastics are manufactured and the waste is dealt with. And BIPOC communities bear the disproportionate burden of it all. Acknowledging and addressing this tradeoff is at the root of the behavioral change that stands between us and a just and healthy circular economy.

In his influential book How To Be An Antiracist, Dr. Ibram X. Kendi argues that if we recognize we live in a society with many racial inequities – and acknowledge that since no racial group is inferior or superior to another, the cause of these inequities are policies and practices – then to be anti-racist is to challenge those policies and practices where we can and create new ones that create equity and justice for all.

Imagine if as part of our commitment to equity in our sustainability efforts, we recognized, acknowledged, and did what we could to address the racial inequities associated with PVC production, and committed right now to stop using PVC unless it was absolutely essential. The plastics industry would howl and point out inconsistencies, question priorities, highlight unintended consequences. We would all feel a tinge of whataboutism – what about carbon, or this other injustice, or that shortcoming of the alternatives. But it is clear that widespread incrementalism is failing us on so many fronts, none more than the environmental injustices that are hardwired into our supply chains.

In fact, there are many examples of companies and building projects that have prioritized PVC-free alternatives based upon principles of equity and justice. We need more leaders in the field to join those who are abandoning vinyl in product types that have superior options. Our CEO Gina Ciganik used a non-PVC flooring in 2015 at The Rose, her last development project prior to joining HBN.

First Community Housing, another affordable housing leader, has been using linoleum for many years for similar reasons. In their Leigh Avenue Apartments project. Forbo’s Marmoleum Click tiles were the flooring of choice.

Vinyl is not an essential material for any of the largest surface areas of our building projects – flooring, wall coverings, or roofing. It may often be the conventional choice in conventional buildings, but it should not be the conventional choice in buildings that promise to be green, healthy, and equitable. LVT may be the fastest growing flooring product in the world, but it is a throwback to the inequitable, unsustainable world we say is unacceptable, not the world we are trying to create.

Habitable can help you start by using our Informed™ product guidance, which helps identify worst and best in class products that are healthier for people and the planet. So why not start here and now, with a principled stand of refusing to profit from unjust, frequently racist, externalized costs?

SOURCES

- https://plasticsrecycling.org/pvc-design-guidance

- See pp. 27-29: www.newplasticseconomy.org/assets/doc/New-Plastics-Economy_Catalysing-Action_13-1-17.pdf

- See e.g. Figure 1: https://css.umich.edu/publication/plastics-us-toward-material-flow-characterization-production-markets-and-end-life

- See e.g.: www.apple.com/environment/answers (Apple); www.greenpeace.org/usa/reports/greener-electronics-2017 (Google); www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-aug-26-fi-16540-story.html (Nike)

- www.greenbiz.com/article/inside-interfaces-bold-new-mission-achieve-climate-take-back: “Going Beyond Zero” The march towards Mission Zero continued unabated, however, with consistent year-over-year improvement in most metrics. Today, the company forecasts that by 2020 it will halve its energy use, power 87 percent of its operations with renewable energy, cut water intake by 90 percent, reduce greenhouse gas emissions 95 percent (and its overall carbon footprint by 80 percent), send nothing to landfills, and source 95 percent of its materials from recycled or biobased resources.

- www.cleanproduction.org/resources/entry/plastics-scorecard-press-release

“When I came here, my unit was on the brink of falling apart. We had so many problems; the carpets were incredibly old, and turning the AC on was like having a helicopter inside the house.”

These are the words of Vanessa del Campo. She was born and raised in Mexico and like many other people, she moved to the United States searching for safer and better living conditions. She now lives in Minnesota and rents a small unit in a multifamily apartment building located in one of the areas designated by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) as of Environmental Justice concern. Her experience as a tenant is filled with stories of unjust evictions, health concerns, and constant battles with unlawful landlords that neglected her right to even the most basic human living conditions.

Fortunately for Vanessa and other neighbors in her building, she received support from a community-based organization, Renters United for Justice (abbreviated IX from its name in Spanish), that helped them organize and mobilize to reclaim desperately needed services to maintain their health and wellbeing. What began as an organized effort to request new windows for a handful of apartment units turned into an exhausting but successful journey to purchase the run-down complex of apartment buildings from their landlord and secure a loan to renovate all the apartments.

It’s easy to get lost in Vanessa’s excitement as she talks about this newfound opportunity. She mentioned that her baby had a tough time learning to crawl because it was too dangerous to place her on the ground due to rats and cockroaches often running past her. At the same time, it is also easy to forget that in addition to being a mother and having a demanding job, she now has to fulfill the role of a building co-owner as a leading member of the newly formed residents’ collective (A Sky Without Limits).

With so much work going into buying and renovating the apartment complex, the residents had little time to think about the chemical safety of their chosen building materials. That’s where HBN came in. In 2021 the MPCA awarded IX and Healthy Building Network a grant to work together to reduce toxic chemical exposures among children, pregnant individuals, employees, and communities who are disproportionately impacted by harmful chemicals used in common products.

One example of toxic chemicals in homes are phthalates, or orthophthalates, which are chemicals that help make plastics flexible. They can also impact the proper development of children. These chemicals are banned in children’s toys in the U.S., and The Minnesota Department of Health in partnership with MPCA named phthalates as “Priority Chemicals” as part of the 2017 Toxic-Free Kids Act. While many manufacturers have phased out hazardous phthalate plasticizers, existing vinyl flooring, especially those installed 2015 and earlier, likely contain these potential developmental toxicants. This translates to dozens of pounds of these hazardous chemicals in the floor of a single apartment unit. As these chemicals are released from products, they deposit in dust, which can be inhaled or ingested by residents – particularly young children who are crawling on floors and often place their hands in their mouths.

“Honestly, we never stopped to think about how harmful [building] materials could be.” Vanessa said. “It was just regrettable to see how we were living. We understand that the new materials that are going into our buildings today may not be the healthiest. Today, we realize it is important to think about how we want to live in our homes, to imagine the quality of life we want in our buildings, in our community.”

Over the coming year, HBN will work with IX and the residents’ collective to evaluate the materials used in their ongoing renovation process and provide recommendations to improve material selection. We will also develop resources tailored to residents to enhance their understanding of how the surrounding environment influences their health. To extend the impact of this work, we will create and share a set of best practices that property managers and tenant organizations can use to advocate for healthier materials in the communities they live in and properties they manage.

“Our collaboration with HBN is timely. By working together with the property managers, we can raise their awareness about how their work impacts our health and help change how they select materials,” Vanessa said.

At Healthy Building Network, we are grateful for the opportunity to work with IX and local leaders like Vanessa through the MPCA grant that makes this collaboration possible. We call on public agencies, foundations, and private investors to fund initiatives that seek to dismantle health inequities through direct investment in the communities disproportionately impacted by environmental injustice, especially related to toxic chemical exposures. We look forward to sharing with you the lessons, stories, and resources that come out of this collaboration.

To learn more about selecting healthier products, visit our Informed™ website, which includes a wide range of resources and tools to help you find healthier material options.

Un inquilino clama por viviendas más seguras y saludables

“Cuando llegué aquí, mi apartamento estaba a punto de desmoronarse. Tuvimos muchos problemas; las alfombras eran increíblemente viejas y encender el aire acondicionado era como tener un helicóptero dentro de la casa”. Estas son las palabras de Vanessa del Campo.

Vanessa nació y creció en México, y como muchas otras personas, se mudó a los Estados Unidos en busca de mejores condiciones de vida. Ahora vive en Minnesota y alquila un apartamento en un edificio multifamiliar ubicado en una de las áreas designadas por la Agencia de Control de Contaminación de Minnesota (MPCA) como de interés de Justicia Ambiental. Su experiencia como inquilina está marcada con historias de desalojos injustos, preocupaciones de salud, y batallas constantes con propietarios que negaron su derecho a incluso las condiciones más básicas de vida.

Afortunadamente para Vanessa y otros vecinos en su edificio, ella recibió el apoyo de Inquilinos Unidos por Justicia (IX), una organización comunitaria que les ayudó a organizarse y movilizarse para recuperar los servicios que desesperadamente necesitaban para mantener su salud y bienestar. Lo que comenzó como un esfuerzo organizado para solicitar nuevas ventanas para un pequeño número de apartamentos, se convirtió en una larga pero exitosa tarea para comprar el destartalado complejo de apartamentos y asegurar un préstamo para renovar todas sus unidades.

“Pasamos por muchos litigios con el propietario porque no estaba haciendo las reparaciones que necesitábamos y no quería vendernos los edificios. El año pasado, cuando llegó la pandemia, finalmente obtuvimos la oportunidad de comprar el edificio. Fue un momento feliz y difícil porque estábamos aterrorizados de enfermarnos [con el virus], pero logramos organizarnos y apoyarnos unos a otros. Hoy estamos trabajando con una nueva empresa de administración de propiedades y el banco para instalar alfombras, pisos, techos, ventanas, hornos, refrigeradores y baños nuevos. Estamos haciendo una profunda renovación para llevar todos los apartamentos a un estado que es mucho, mucho mejor que el que teníamos”.

Es fácil dejarse llevar por la emoción de Vanessa mientras habla de esta nueva oportunidad. Ella mencionó que su bebé tuvo dificultades para aprender a gatear porque era demasiado peligroso colocarle en el suelo debido a las ratas y cucarachas que a menudo rondaban la casa. Al mismo tiempo, también es fácil olvidar que además de ser madre y tener un trabajo exigente, ahora tiene que cumplir el rol de copropietaria de un edificio como miembro principal de un recién formado colectivo de residentes (Un Cielo Sin Límites).

Con tanto trabajo invertido en la compra y renovación del complejo de apartamentos, los residentes tuvieron poco tiempo para pensar en la seguridad química de los materiales de construcción que fueron utilizados en sus apartamentos. Ahí es donde entra Healthy Building Network (HBN, o, La Red de Edificios Saludables). A principios de este año, MPCA otorgó a IX y HBN una subvención para reducir la exposición a sustancias químicas tóxicas entre los niños, las personas embarazadas, los empleados y las comunidades que se ven afectadas de manera desproporcionada por sustancias químicas nocivas utilizadas en productos comunes.

Un ejemplo de sustancias químicas tóxicas en los hogares son los ftalatos u ortoftalatos, que son sustancias químicas utilizadas para ayudar a dar flexibilizar a los plásticos. Estas sustancias también pueden afectar el desarrollo adecuado de los niños. Estos productos químicos están prohibidos en los juguetes de los niños en los EE. UU. El Departamento de Salud de Minnesota, en asociación con MPCA, nombró a los ftalatos como “productos químicos prioritarios” como parte de la Ley de Niños Libres de Tóxicos de 2017. Si bien muchos fabricantes han eliminado los plastificantes de ftalato, estos químicos están presentes en los pisos de vinilo existentes, especialmente los instalados antes de 2016. Esto se traduce en docenas de libras de estos químicos peligrosos en el piso de una sola unidad de apartamento. A medida que estos productos químicos se liberan de los productos, se depositan en el polvo que los residentes pueden inhalar o ingerir, afectando especialmente a los niños pequeños que gatean por el suelo y a menudo se llevan las manos a la boca.

“Honestamente, nunca nos detuvimos a pensar en lo dañino que podrían ser los materiales [de construcción]”. Dijo Vanessa. “Fue lamentable ver cómo vivíamos. Entendemos que los materiales que se utilizan en nuestros edificios hoy en día pueden no ser los más saludables. Hoy nos damos cuenta de que es importante pensar en cómo queremos vivir en nuestros hogares, imaginar la calidad de vida que queremos en nuestros edificios, en nuestra comunidad”.

Durante el próximo año, HBN trabajará con IX y el colectivo de residentes para evaluar los materiales utilizados en su proceso de renovación y brindar recomendaciones para mejorar la selección de materiales. También desarrollaremos recursos para ayudar a los residentes a entender cómo el entorno circundante influye en su salud. Para extender el impacto de este trabajo, crearemos y compartiremos un conjunto de mejores prácticas para que los administradores de propiedades y las organizaciones de inquilinos puedan abogar por utilizar materiales más saludables en las comunidades en las que viven y en las propiedades que administran.

“Nuestra colaboración con HBN es oportuna. Al trabajar junto con los administradores de propiedades, podemos aumentar su conciencia sobre cómo su trabajo impacta nuestra salud y ayudar a cambiar la forma en que seleccionan los materiales”, dijo Vanessa.

En Healthy Building Network, estamos agradecidos por la oportunidad de trabajar con IX y líderes locales como Vanessa a través de la subvención otorgada por MPCA que hace posible esta colaboración. Hacemos un llamado a las agencias públicas, fundaciones e inversionistas privados para que financien iniciativas que busquen desmantelar las inequidades en salud a través de inversión en las comunidades impactadas de manera desproporcionada por la injusticia ambiental, especialmente relacionada con la exposición a sustancias químicas tóxicas. Esperamos pronto poder compartir con ustedes las lecciones, historias y recursos que surgen de esta colaboración.

Plastic is a ubiquitous part of our everyday lives, and its global production is expected to more than triple between now and 2050. According to industry projections, we will create more plastics in the next 25 years than have been produced in the history of the world so far.

The building and construction industry is the second largest use sector for plastics after packaging.1 From water infrastructure to roofing membranes, carpet tiles to resilient flooring, and insulation to interior paints, plastics are ubiquitous in the built environment.

These plastic materials are made from oil and gas. And, due to energy efficiency improvements, for example–in building operations and transportation–the production and use of plastics is predicted to soon be the largest driver of world oil demand.2

Plastic building products are often marketed in ways that give the illusion of progress toward an ill-defined future state of plastics sustainability. For the past 20 years, much of that marketing has focused on recycling. But for a variety of reasons, these programs have failed.

A recent study from the University of Michigan makes it clear that the scale of post-consumer plastics recycling in the US is dismal.3 Only about 8% of plastic is recycled, and virtually all of that is beverage containers. Further, most of the recyclate is downcycled into products of lower quality and value that themselves are not recyclable. For plastic building materials, the numbers are more dismal still. For example, carpet, which claims to have one of the more advanced recycling programs, is recycled at only a 5% rate, and only 0.45% of discarded carpet is recycled into new carpet. The rest is downcycled into other materials, which means their next go-around these materials are destined to be landfilled or burned.4 After 20 years of recycling hype, post-consumer recycling of plastic building materials into products of greater or equal value is essentially non-existent, and therefore incompatible with a circular economy.

Why isn’t plastic from building materials recycled?

Additives (which may be toxic), fillers, adhesives used in installation, and products made with multiple layers of different types of materials all make recycling of plastic building materials technically difficult. Lack of infrastructure to collect, sort, and recycle these materials contributes to the challenge of recycling building materials into high-value, safe new materials.

Manufacturers have continued to invest in products that are technically challenging to reuse or recycle – initially cheaper due to existing infrastructure – instead of innovating in new, circular-focused solutions. Additionally, their investment in plastics recycling has been paltry. In 2019 BASF, Dow, ExxonMobill, Shell and numerous other manufacturers formed the Alliance to End Plastic Waste (AEPW) and pledged to invest $1.5 billion over the next five years into research and development of plastic waste management technologies. Compare that to the over $180 billion invested by these same firms in new plastic manufacturing facilities since 2010.5

Globally, regulations that discourage or ban landfilling of plastics have, unfortunately, not led to more recycling overall. Instead, burning takes the place of landfilling as the eventual end of life for most plastics.

Confusing rhetoric around plastic end of life options can make this story seem more complicated than it is.6

- “incineration” or “waste to energy” burns plastic for energy.

- “Plastic-to-fuel” or “gasification” or “pyrolysis” generates fuel. This output is rarely used for anything but burning due to the additional processing required to use for any other purpose.

- “Chemical recycling” could, in theory, lead to new plastic products. This technology is unproven and currently not a scalable solution. The outputs are often burned due to low quality.

Plastic waste burning, regardless of the euphemism employed, is a well established environmental health and justice concern.

Burning plastics creates global pollution and has environmental justice impacts.

In its exhaustive 2019 report, the independent, nonprofit Center for International Environmental Law (CEIL) documents how burning plastic wastes increases unhealthy toxic exposures at every stage of the process. Increased truck traffic elevates air pollution, as do the emissions from the burner itself. Burned plastic produces toxic ash and residue at approximately one fifth the volume of the original waste, creating new disposal challenges and new vectors of exposure to additional communities that receive these wastes.7

In the US, eight out of every 10 solid waste incinerators are located in low-income neighborhoods and/or communities of color.8 This means, in some cases, the same communities that are disproportionately burdened with the pollution and toxic chemical releases related to the manufacture of virgin plastics are again burdened with its carbon and chemical releases when it is inevitably burned at the end of its life.

The issue is global in scale. A recent report by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) found that “plastic waste incineration has resulted in disproportionately dangerous impacts in Global South countries and communities.” The Global Alliance for Incineration Alternatives (GAIA), a worldwide alliance of more than 800 groups in over 90 countries, has been working for more than 20 years to defeat efforts to massively expand incineration, especially in the Global South. GAIA members have identified incineration not only as an immediate and significant health threat in their communities, but also a major obstacle to resource conservation, sustainable economic development, and environmental justice.

Where do we go from here?

- Minimize production of virgin plastic. This should be the main focus of any plastic waste reduction plan and part of any comprehensive climate change initiative. Policies banning single use plastics or banning the construction of new plastic production facilities or facility expansions are two example solutions cited by GAIA.9 Less plastic means less waste and less material to incinerate.

- Invest in true circular economy initiatives. These may include, for example: extended producer responsibility programs, materials passports, materials disclosure, elimination of toxic chemical additives, product as a service models, and recycling facilities that support upcycling. By shifting industry investments toward circular economy infrastructure – instead of the nearly $200 billion investments in increased manufacturing and burning capacity – the plastic industry could start to be part of the solution of reducing plastic waste.

- When evaluating the “expense” of recycling and circularity vs business-as-usual, a fair calculation for the latter needs to include all costs associated with the production, use, and end of life impacts of plastics. That “cheap” vinyl floor is no longer so inexpensive when the full costs of global pollution and the health burdens of people of color and low income communities are included in the math. Externalities must be a part of the equation.

What is unquestionable is this: Today our only choices for plastic waste are to burn or landfill most of it. Expanding plastics production and incineration is a conscious decision to perpetuate well documented, fully understood inequity and injustice in our building products supply chain.

The folks at The Story of Stuff cover this in The Story of Plastics, four minute animated short suitable for the whole family. Comedian John Oliver tells the “R-rated” version of the story with impeccable research and insightful humor in his HBO show Last Week Tonight. It’s worth a look to learn exactly how the plastics industry uses the illusion of recycling to sell ever increasing volumes of plastic. Without manufacturer responsibility and investment, efforts to truly incorporate plastic into a circular economy have little chance of success.

SOURCES

- https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution

- https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/bee4ef3a-8876-4566-98cf-7a130c013805/The_Future_of_Petrochemicals.pdf See page 18, 30.

https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/us-energy-facts/ - https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab9e1e/pdf

- https://carpetrecovery.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CARE-2019-Annual-Report-6-7-20-FINAL-002.pdf

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jan/21/founders-of-plastic-waste-alliance-investing-billions-in-new-plants

- https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/False-solutions_Nov-9-2020.pdf

- https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Plastic-and-Climate-FINAL-2019.pdf

- https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d14dab43967cc000179f3d2/t/5d5c4bea0d59ad00012d220e/1566329840732/CR_GaiaReportFinal_05.21.pdf

- https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/False-solutions_Nov-9-2020.pdf

In Louisiana, the factories that make the chemicals and plastics for our building products are built literally upon the bones of African Americans. Plantation fields have been transformed into industrial fortresses.

A Shell Refinery1 sprawls across the former Bruslie and Monroe plantations. Belle Pointe is now the DuPont Pontchartrain Works, among the most toxic air polluters in the state.2 Soon, the Taiwan-based Formosa Plastics Group intends to build a 2400-acre complex of 14 facilities that will transform fracked gas into plastics. It will occupy land that was formerly the Acadia and Buena Vista plantations, and not incidentally, the ancestral burial grounds of local African American residents, some of whom trace their lineage back to people enslaved there.3

Formosa has earned a reputation of being a poor steward of sacred places. Local residents have petitioned the Governor to deny permits for the facility, citing a long list of environmental health violations in its existing Louisiana facilities, including violations of the Clean Air Act every quarter since 2009.4 The scofflaw company was found to have dumped plastic pellets known as “nurdles” into the fragile ecosystem of Lavaca Bay on the Gulf of Mexico for years – leading to a record $50 million settlement with activists in that community in 2019.5

In the Antebellum South, formerly enslaved people often homesteaded on lands that were part of or near the plantations they once worked. They established communities of priceless historical and cultural worth, towns such as Morrisonville, Diamond, Convent, Donaldsonville, and St. James. Donaldsonville, Louisiana, is the town that elected Pierre Caliste Landry, America’s first African American mayor in 1868, just three years after the end of the Civil War. This part of Louisiana holds many layers of complex and deep African American history.

But in the last 75 years, since World War II, these communities have been overrun by petrochemical industry expansion enabled by governments wielding the clout of Jim Crow laws to snuff out any opposition or objection. Towns like Morrisonville and Diamond have been bought up to accommodate plant expansion. Residents have been forced to move out, their history and heritage literally paved over. It wasn’t until 1994 that the River Road African American Museum was established to preserve and present the history of the Black population as distinct from plantation representations of slavery. According to Michael Taylor, Curator of Books, Louisiana State University Libraries: “Only in the last few decades have historians themselves begun to appreciate the complexity of free black communities and their significance to our understanding not just of the past, but also the present.”6

Charting a New Way Forward—Together

Virtually every building product we use today contains a petrochemical component that originates from heavily polluted communities, frequently home to people of color. As the green building movement searches for ways to enhance diversity, inclusion and equity, how might it address the legacies of injustice that are tied to the products and materials we use every day?

Architect, Zena Howard, FAIA, offered insight in her 2019 J. Max Bond Lecture, Planning to Stay, keynoting the National Organization of Minority Architects national conference. Howard, known for her work on the design team for the breathtaking Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, most often works with people in communities whose culture and heritage were “erased” by urban renewal in the 1960’s. In Greenville, North Carolina, she looked to people from the historically African American Downtown Greenville community and Sycamore Hill Missionary Baptist Church Congregation to guide the planning and design process for a new town common and gateway plaza. The goal was not to “replicate” the lost community, but to bring its history and present day aspirations to life in the new design. In Vancouver, British Columbia, the development plan for a neighborhood founded by African Canadian railroad porters included an unprecedented chapter on “reconciliation and cultural redress.” The key to such efforts, according to Howard is co-creation and meaningful collaboration, whose Greek roots, she notes, mean “to labor together.”

How might we labor together to address environmental injustice when evaluating the overall healthfulness and equity of our building materials? The precedent of “insetting” suggests an approach.

Insetting has been pioneered by companies whose supply chains rely upon agricultural communities across the globe. According to Ceres, insetting is “a type of carbon emissions offset, but it’s about much more than sequestering carbon: It’s also about companies building resiliency in their supply chains and restoring the ecosystems on which their growers depend.”

In previous columns, I’ve addressed concerns about the social in industrial communities, e.g., proposals that perpetuate disproportionate pollution impacts when buying offsets rather than addressing emissions from a specific facility. Applying the “insetting” approach we might ask our materials manufacturers—and the communities that are home to the building materials industries—what steps can we take to encourage manufacturers to “labor with” communities seeking environmental justice, such as those along the Mississippi River? Can we, together, resurrect and restore their history, reconcile and redress historical wrongs, and build a healthier future for all?

Black History

Month Readings

To learn more about the history and present day conditions of Cancer Alley, see these excellent articles from The Guardian and Pro Publica: https://www.ehn.org/search/?q=cancer+alley

You can watch to Zena Howard’s J. Max Bond lecture, Planning to Stay, here: https://vimeo.com/378622662

You can learn more about the River Road African American History Museum here: https://africanamericanmuseum.org/

SOURCES

- Terry L. Jones, “Graves of 1,000 Enslaved People Found near Ascension Refinery; Shell, Preservationists to Honor Them | Ascension | Theadvocate.Com,” accessed February 18, 2020, https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/communities/ascension/article_18c62526-2611-11e8-9aec-d71a6bbc9b0c.html.

- Oliver Laughland and Jamiles Lartey, “First Slavery, Then a Chemical Plant and Cancer Deaths: One Town’s Brutal History,” The Guardian, May 6, 2019, sec. US news, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/may/06/cancertown-louisiana-reserve-history-slavery.

- Sharon Lerner, “New Chemical Complex Would Displace Suspected Slave Burial Ground in Louisiana’s ‘Cancer Alley,’” The Intercept (blog), December 18, 2019, https://theintercept.com/2019/12/18/formosa-plastics-louisiana-slave-burial-ground/.

- Louisiana Bucket Brigade, “Sign the Petition,” Change.org, accessed February 25, 2020, https://www.change.org/p/governor-edwards-stop-the-formosa-chemical-plant.

- Stacy Fernández, “Plastic Company Set to Pay $50 Million Settlement in Water Pollution Suit Brought on by Texas Residents,” The Texas Tribune, October 15, 2019, https://www.texastribune.org/2019/10/15/formosa-plastics-pay-50-million-texas-clean-water-act-lawsuit/.

- LSU Libraries, “Free People of Color in Louisiana,” LSU Libraries, accessed February 18, 2020, https://lib.lsu.edu/sites/all/files/sc/fpoc/history.html.

Discover how bisphenols and phthalates, commonly used in plastics for added strength or flexibility, can disrupt hormone function, and learn ways to reduce their use for improved health in this informative video.

The Future of Petrochemicals report explores the role of the petrochemical sector in the global energy system and its increasing significance for energy security and the environment, highlighting the need for attention from policymakers.

Polyethylene is the world’s most common plastic. It is used in packaging, food and beverage containers, and consumer products.

Building product manufacturers sometimes use post-consumer recycled polyethylene bags and bottles in pipes and plastic lumber. This scrap usually has minimal contents of concern, but products like detergents stored in plastic packaging can remain. So-called “bio-degradation” agents in plastic bags also contaminate this feedstock and should never be used. The plastics recycling industry is developing protocols to screen out residual contaminants. Of greatest concern: Most polyethylene goes unrecycled in the United States due to problems in supply chain controls and the low price of virgin resins. This report examines ways to optimize the use of post-consumer polyethylene in building materials.

Not all recycled content materials are created equal – especially when it comes to recycled plastics.

In a report released by StopWaste and the Healthy Building Network, we take an in-depth look at the health implications, supply chain considerations, and potential to scale up recycling of the world’s most common plastic: polyethylene (aka PE). [1] This report, Post-Consumer Polyethylene in Building Products, is the latest installment in our Optimizing Recycling series.

Polyethylene is a material widely used in product packaging, beverage containers, and myriad consumer products. High Density Polyethylene (HDPE), Low Density Polyethylene (LDPE), and Linear Low Density Polyethylene (LLDPE) are all readily recyclable in California. Polyethylene plastic scrap bottles and plastic bags usually have minimal contents of concern and are easily processed into feedstock for new products, including building materials. Despite the great potential for recovery of PE, sizeable barriers stand in the way of a lot more recycling.

The explosive growth in virgin ethylene production on the U.S. Gulf Coast, driven by cheap energy, has meant that most post-consumer scrap PE is either landfilled, incinerated, or sent overseas for processing. [2]

Industry trends in recycling collection technology are also undermining the value of post-consumer polyethylene feedstocks. Pipe and plastic lumber manufacturers in the U.S. require supplies that have minimal amounts of contaminants such as volatile residual substances in packaging and other types of plastics. Yet proportionally less “good material” is coming out of the plastic waste recycling stream due to the rising use of municipal single stream recycling over the past decade. Mixed and low quality scrap materials that come from single-stream recycling centers are more likely to be exported than sorted and screened for high-quality polyethylene scrap. As a result, more recovered plastic bags are exported than processed domestically. [3]

Additives used for plastics can turn into contaminants when recycled. As seen with other recycled content materials, feedstocks with less contamination have an increased potential for recyclability as well as increased value to purchasers. [4] For PE, contaminants come in the form of residual materials from packaging (residue from bottles that contained pesticides, for example), or from additives used in manufacturing to achieve certain product characteristics. Perhaps the most problematic additive to PE products are so-called biodegradation additives used in plastic packaging. These additives (but not the rest of the plastic) degrade when exposed to sunlight or other environmental conditions. When these products are collected and used as post-consumer recycled feedstocks in products like pipes and decking, however, these additives can lower the reliability and value of a manufacturer’s product. This is why, in our report, we recommend that plastic manufacturers stop using degradability additives in all new polyethylene.

SOURCES

- Polyethylene sales accounted for 35% of all USA plastic resin sales in 2014. The next most common resins, polypropylene and polyvinyl chloride, accounted for 15 percent and 14 percent, respectively. (American Chemistry Council. “2015 Resin Review,” April 2015.)

- In 2005, the Healthy Building Network and the Institute for Local Self-Reliance examined the market for lumber made from recycled plastic. The report rated fourteen plastic lumber products as “most environmentally preferable” because they contained only polyethylene plastics and, according to the manufacturer at the time, at least 50% of the polyethylene was from post-consumer sources. (Platt, Brenda, Tom Lent, and Bill Walsh. “The Healthy Building Network’s Guide to Plastic Lumber.” Institute for Local Self-Reliance, June 2005. https://www.greenbiz.com/sites/default/files/document/CustomO16C45F64528.pdf.) At least eight of these fourteen products remain on the market, but current literature reveals that most if not all have decreased post-consumer content in favor of pre-consumer (factory-generated) scrap or even virgin polyethylene. Plastic lumber products listed in the report that are still on the market include: SelectForce; PlasTEAK; TRIMAX; American Plastic Lumber’s HPDE decking; Perma-Deck Advantage+; Eco-Tech; Enviro-Curb; and MAXiTUF. Resco Plastics, manufacturer of MAXiTUF plastic lumber, explains, “Due to the current price increases for our raw material, Resco Plastics, Inc. is no longer able to guarantee its post consumer content.” (Resco Plastics Incorporated. “Plastic Lumber Warranty,” 2016. http://rescoplastics.com/warranty/.)

- Plastic scrap exports to Asia have soared since 2000. This trend continued through 2013, the most recent year for which data are available from the Society of the Plastics Industry. Of the plastic film collected for recycling in the US, only 42 percent was processed in the U.S. or Canada. Shippers exported the remaining 58 percent. (Taylor, Michael D. “The State of Plastics Recycling in the U.S.” presented at the 11th China International Forum on Development of the Plastics Industry & China Plastics Recycling/ Reutilization Forum, Yuyao, China, October 2015. http://www.slideshare.net/mdairtaylor/the-state-of-plastics-recycling-in-the-us.)

- See our report Optimizing Recycling: Criteria for Comparing and Improving Recycled Feedstocks in Building Products for more on how additives and contaminants can affect common post-consumer recycled feedstock materials markets.

Climate Change

Climate Change Pollution

Pollution Equity

Equity Health

Health