READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

Building products incorporating antimicrobial additives are becoming increasingly prevalent. Paints, and other touchable surfaces such as countertops, and virtually any product considered as an interior finish may contain one or a combination of antimicrobials. These agents are considered pesticides, but their identity—and related hazards—can be difficult for the average person to discover. This lack of transparency creates a hurdle for the informed selection of products with reduced negative impacts.

No evidence yet exists to demonstrate that products intended for use in interior spaces that incorporate antimicrobial additives actually result in healthier populations. Further, antimicrobials may have negative impacts on both people and the environment. This paper, prepared by Perkins&Will in partnership with HBN, aims to present current information about reported or potential health and environmental impacts of antimicrobial substances as commonly used within the building industry, and to assist architects, designers, building owners, tenants, and contractors in understanding those impacts.

In response to growing concerns over COVID-19, Healthy Building Network (HBN) and global architecture and design firm Perkins and Will reexamined and reaffirmed the conclusions and recommendations of this white paper.

Asphalt (also known as asphalt concrete, bitumen, or road tar) is the most common paving material by far, accounting for a 92 percent share of the 2.5 million miles of roads and highways in the United States. Reclaiming and reusing asphalt has many benefits, including waste prevention, reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, and lower lifecycle impacts compared to virgin asphalt material use.

Keys to increasing the recycling of asphalt and its attendant environmental benefits include simplifying the designs of asphalt mixes, reducing toxic additives in production, tracking materials from production through use and recycling, testing incoming materials for contaminants, and avoiding the addition of cutback solvents and other toxic rejuvenating agents.

Research from Healthy Building Network (HBN) documents how vinyl building products, also known as PVC or polyvinylchloride plastic, are the number one driver of asbestos use in the US.

The vinyl/asbestos connection stems from the fact that PVC production is the largest single use for industrial chlorine, and chlorine production is the largest single consumer of asbestos in the US. [1] More than 70% of PVC is used in building and construction applications – pipes, flooring, window frames, siding, wall coverings and membrane roofing. [2] This makes the building and construction industry the single largest product sector consuming chlorine, bearing sizeable responsibility for the ongoing demand for asbestos. [3]

Despite the existence of asbestos (and mercury) free chlorine production methods, the PVC industry has positioned itself at the vanguard of industry efforts to frustrate stronger asbestos regulation. According to Mike Belliveau, the Executive Director of the Environmental Health Strategy Center and a senior advisor to Safer Chemicals Healthy Families coalition, “The PVC market has spurred chemical industry lobbyists to urge the Trump Administration to exempt their use of deadly asbestos from future restrictions.” The last time the vinyl industry positioned themselves so publicly on the other side of common sense, they were defending the use of lead in children’s vinyl lunch boxes.

Among HBN’s Findings:

- The U.S. chlor-alkali industry (Olin/Dow, Occidental, and Westlake/Axiall [4]) consumed 88% of asbestos imports in 2014, and all asbestos imports in 2016.

- Three U.S. chemical companies are importing 1.2 million pounds of asbestos per year for use in 15 chlor-alkali plants. PVC used in building products requires an estimated 250,000 pounds of imported asbestos per year.

- Asbestos miners in Minaçu, Brazil, are literally dying to prop up the U.S. chemical and PVC building product industries’ reliance on asbestos. Dozens of asbestos baggers are dying or have died of asbestos related diseases, according to local reports. [5] Overall, Brazil exports over 13,000 bags of asbestos each year to the U.S. chlorine industry.

- Occidental Chemical imported 900,000 pounds of asbestos from Oct. 2013 through 2015, but apparently failed to report those imports to the EPA in possible violation of the Chemical Data Reporting rule as required under TSCA.

- Asbestos imports by Occidental Chemical and Olin Corporation more than doubled from 2015 to 2016, perhaps indicating a stockpiling of asbestos in anticipation of further restrictions on mining in Brazil or use in the U.S.

- Russia shipped asbestos to Dow in 2014 and to Olin in 2016 (when Olin took over Dow’s U.S. chlor-alkali plants). If the mine in Brazil closes, the U.S. chlor-alkali industry’s backup plan is the massive mine in Asbest, Russia.

The health hazards of asbestos exposure, painful and deadly lung diseases including cancer, are clear. Green building professionals do not have to wait. Do your part to prevent asbestos-related diseases here and abroad. Don’t specify vinyl building products.

SOURCES

1. In the US more than half of chlorine is produced using asbestos, despite the availability of an alternative production method that does not require either asbestos or mercury.

2. http://www.vinylinfo.org/vinyl/uses

3. According to IHS Markit, “A majority of chlor-alkali capacity is built to supply feedstock for ethylene dichloride (EDC) production. EDC is then used to make vinyl chloride (VCM) and subsequently used to manufacture polyvinyl chloride (PVC). This chain, EDC to VCM to PVC, is normally called the vinyl chain. PVC demand correlates closely with construction spending, therefore, it can be concluded that chlorine consumption and production are driven by the construction industry. Hence, chlorine consumption growth depends on the growth of the global economy, since a country will spend more on construction if it has a healthy gross domestic product.” (IHS Markit. “Chemical Economics Handbook: Chlorine/Sodium Hydroxide (Chlor-Alkali),” December 2014. https://www.ihs.com/products/chlorine-sodium-chemical-economics-handbook.html)

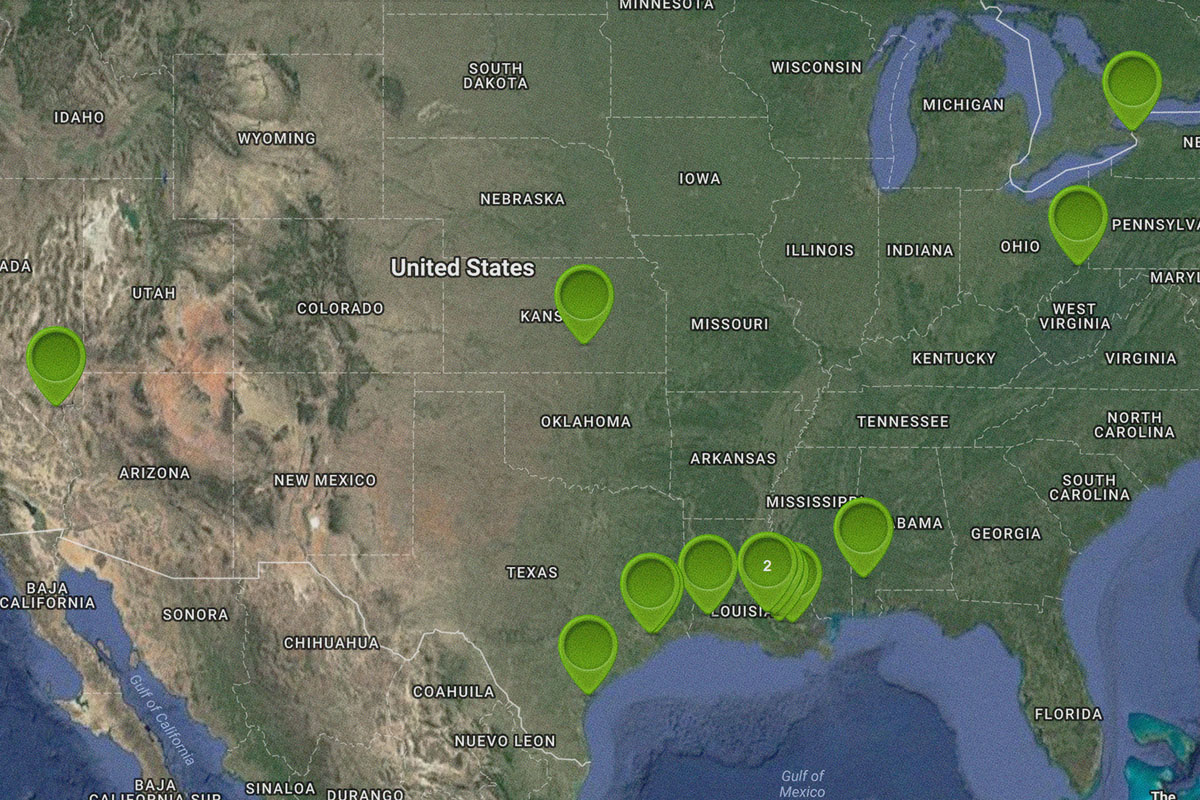

4. Fifteen chlor-alkali plants last reported to be using asbestos diaphragms include, in order of estimated chlorine capacity:

-

- Olin (formerly Dow), Freeport, Tex. (3,158,000 tons per year)

- Westlake (formerly Axiall), Lake Charles, La. (1,100,000 tpy)

- Olin, Plaquemine, La. (1,068,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Ingleside/Corpus Christi, Tex. (668,000 tpy)

- Occidental, La Porte, Tex. (580,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Hahnville/Taft, La. (567,000 tpy)

- Olin, McIntosh, Ala. (468,000 tpy)

- Westlake, Plaquemine, La. (410,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Convent, La. (389,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Niagara Falls, N.Y. (336,000 tpy)

- Westlake, Natrium/New Martinsville, W.Va. (297,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Geismar, La. (273,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Wichita, Kans. (182,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Deer Park, Tex. (162,500 tpy)

- Olin, Henderson, Nev. (153,000 tpy)

5. Carpentier, Steve. “Minaçu, a cidade que respira o amianto.” CartaCapital, May 21, 2013. http://www.cartacapital.com.br/sustentabilidade/minacu-a-cidade-que-respira-o-amianto-8717.html

Healthy Building Network’s research into current recycling practices for flexible polyurethane foam (FPF) indicates that most post-consumer feedstocks are contaminated with highly toxic flame retardants.

Discussions of recycling FPF have centered around the human health and environmental hazards posed by the flame retardant PentaBDE, which the foam industry phased out a decade ago. But the flame retardants that have replaced PentaBDE present similar concerns. Manufacturers incorporate flame retardant-laden post-consumer FPF into new products, primarily bonded carpet cushion. Recycling and installation workers and building occupants, particularly crawling children, can be exposed to these toxic chemicals. The recent emergence of pre-consumer FPF scrap that is free of flame retardants is a great step toward a safer, more valuable feedstock, but more work is needed to track and label flame retardant-free FPF to ensure that future post-consumer foam is also flame retardant-free.

Polyethylene is the world’s most common plastic. It is used in packaging, food and beverage containers, and consumer products.

Building product manufacturers sometimes use post-consumer recycled polyethylene bags and bottles in pipes and plastic lumber. This scrap usually has minimal contents of concern, but products like detergents stored in plastic packaging can remain. So-called “bio-degradation” agents in plastic bags also contaminate this feedstock and should never be used. The plastics recycling industry is developing protocols to screen out residual contaminants. Of greatest concern: Most polyethylene goes unrecycled in the United States due to problems in supply chain controls and the low price of virgin resins. This report examines ways to optimize the use of post-consumer polyethylene in building materials.

Not all recycled content materials are created equal – especially when it comes to recycled plastics.

In a report released by StopWaste and the Healthy Building Network, we take an in-depth look at the health implications, supply chain considerations, and potential to scale up recycling of the world’s most common plastic: polyethylene (aka PE). [1] This report, Post-Consumer Polyethylene in Building Products, is the latest installment in our Optimizing Recycling series.

Polyethylene is a material widely used in product packaging, beverage containers, and myriad consumer products. High Density Polyethylene (HDPE), Low Density Polyethylene (LDPE), and Linear Low Density Polyethylene (LLDPE) are all readily recyclable in California. Polyethylene plastic scrap bottles and plastic bags usually have minimal contents of concern and are easily processed into feedstock for new products, including building materials. Despite the great potential for recovery of PE, sizeable barriers stand in the way of a lot more recycling.

The explosive growth in virgin ethylene production on the U.S. Gulf Coast, driven by cheap energy, has meant that most post-consumer scrap PE is either landfilled, incinerated, or sent overseas for processing. [2]

Industry trends in recycling collection technology are also undermining the value of post-consumer polyethylene feedstocks. Pipe and plastic lumber manufacturers in the U.S. require supplies that have minimal amounts of contaminants such as volatile residual substances in packaging and other types of plastics. Yet proportionally less “good material” is coming out of the plastic waste recycling stream due to the rising use of municipal single stream recycling over the past decade. Mixed and low quality scrap materials that come from single-stream recycling centers are more likely to be exported than sorted and screened for high-quality polyethylene scrap. As a result, more recovered plastic bags are exported than processed domestically. [3]

Additives used for plastics can turn into contaminants when recycled. As seen with other recycled content materials, feedstocks with less contamination have an increased potential for recyclability as well as increased value to purchasers. [4] For PE, contaminants come in the form of residual materials from packaging (residue from bottles that contained pesticides, for example), or from additives used in manufacturing to achieve certain product characteristics. Perhaps the most problematic additive to PE products are so-called biodegradation additives used in plastic packaging. These additives (but not the rest of the plastic) degrade when exposed to sunlight or other environmental conditions. When these products are collected and used as post-consumer recycled feedstocks in products like pipes and decking, however, these additives can lower the reliability and value of a manufacturer’s product. This is why, in our report, we recommend that plastic manufacturers stop using degradability additives in all new polyethylene.

SOURCES

- Polyethylene sales accounted for 35% of all USA plastic resin sales in 2014. The next most common resins, polypropylene and polyvinyl chloride, accounted for 15 percent and 14 percent, respectively. (American Chemistry Council. “2015 Resin Review,” April 2015.)

- In 2005, the Healthy Building Network and the Institute for Local Self-Reliance examined the market for lumber made from recycled plastic. The report rated fourteen plastic lumber products as “most environmentally preferable” because they contained only polyethylene plastics and, according to the manufacturer at the time, at least 50% of the polyethylene was from post-consumer sources. (Platt, Brenda, Tom Lent, and Bill Walsh. “The Healthy Building Network’s Guide to Plastic Lumber.” Institute for Local Self-Reliance, June 2005. https://www.greenbiz.com/sites/default/files/document/CustomO16C45F64528.pdf.) At least eight of these fourteen products remain on the market, but current literature reveals that most if not all have decreased post-consumer content in favor of pre-consumer (factory-generated) scrap or even virgin polyethylene. Plastic lumber products listed in the report that are still on the market include: SelectForce; PlasTEAK; TRIMAX; American Plastic Lumber’s HPDE decking; Perma-Deck Advantage+; Eco-Tech; Enviro-Curb; and MAXiTUF. Resco Plastics, manufacturer of MAXiTUF plastic lumber, explains, “Due to the current price increases for our raw material, Resco Plastics, Inc. is no longer able to guarantee its post consumer content.” (Resco Plastics Incorporated. “Plastic Lumber Warranty,” 2016. http://rescoplastics.com/warranty/.)

- Plastic scrap exports to Asia have soared since 2000. This trend continued through 2013, the most recent year for which data are available from the Society of the Plastics Industry. Of the plastic film collected for recycling in the US, only 42 percent was processed in the U.S. or Canada. Shippers exported the remaining 58 percent. (Taylor, Michael D. “The State of Plastics Recycling in the U.S.” presented at the 11th China International Forum on Development of the Plastics Industry & China Plastics Recycling/ Reutilization Forum, Yuyao, China, October 2015. http://www.slideshare.net/mdairtaylor/the-state-of-plastics-recycling-in-the-us.)

- See our report Optimizing Recycling: Criteria for Comparing and Improving Recycled Feedstocks in Building Products for more on how additives and contaminants can affect common post-consumer recycled feedstock materials markets.

When one waste disposal option closes, another inevitably opens.

A half-century ago, the federal government started regulating solid wastes and preventing rampant dumping in the woods, ocean, and unlined dumps. Then the so-called Not-In-My-Backyard (NIMBY) movement of the 1970s and 1980s prevented scores of landfills and incinerators from being permitted across the country, just as existing disposal sites were reaching capacity. There were also spectacular failures at waste sites that made headlines. Coal ash ponds failed, releasing contaminated waste into rivers and drinking water. Giant piles of tires caught on fire, and came to symbolize the crisis of growing piles of waste.

In response, environmental agencies partnered with waste generators like the coal power and tire industries to find ways to reduce the amount of their wastes going to landfills. The US Environmental Protection Agency developed an option called “beneficial use,” in which these wastes could be diverted to build roads, fill old mines, and turn wastelands into golf courses. Some of these “beneficial uses” hit literally close to home; coal waste has been diverted into wallboard and carpet backing, tires into flooring, and contaminated soils into our own backyards, without any regulation.

In two articles, we describe the impacts of this waste management strategy.

“On Tire Wastes in Playgrounds” reveals how chopped up tire mulch is becoming as common as dirt in playgrounds, and why government health agencies are beginning to take action to protect children from exposure to toxic substances in the rubber waste, like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and lead.

“Filled with Uncertainty: Toxic Dirt in Building & Construction” examines the unregulated dirt trade. Our research found that soil and coal ash contaminated with neurotoxic substances have become commonplace construction materials, from structural fill to flower bed topsoil. Contaminated material is often sold as “clean fill” by untrustworthy companies. With no tracking in place, building owners have no idea, and probably don’t think to ask, where their fill is coming from.

Waste has a way of finding the path of least resistance. A void of oversight coupled with numerous government and private sector incentives promoting the use of unregulated recycled content leaves it to responsible architects, designers, contractors and building owners to increase scrutiny of this vast diversion of wastes into our homes, schools, playgrounds and places of business. In the absence of political will, building owners and residents are left to protect themselves. We hope these articles will lead developers, especially of residential areas and playgrounds, to start asking more questions of dirt and fill contractors, beginning with: where did your materials come from, and have they been tested for toxic contaminants?

The recycling industry has made significant strides toward a closed loop material system in which the materials that make up new products today will become the raw material used to manufacture products in the future. However, contamination in some sources of recycled content raw material (“feedstock”) contain potentially toxic substances that can devalue feedstocks, impede growth of recycling markets, and harm human and environmental health.

Since May 2014, the Healthy Building Network, in collaboration with StopWaste and the San Francisco Department of Environment, has been evaluating 11 common post-consumer recycled-content feedstocks used in the manufacturing of building products. This paper is a distillation of that larger effort, and provides analysis on two major feedstocks found in building products: recycled PVC and glass cullet. This research partnership seeks to provide manufacturers, purchasers, government agencies, and the recycling industry with recommendations for optimizing the use of recycled content feedstocks in building products in order to increase their value, marketability and safety. This report was prepared in support of a research session at the 2015 Greenbuild conference in Washington, DC.

New HBN research reveals that legacy toxic hazards are being reintroduced into our homes, schools and offices in recycled vinyl content that is routinely added to floors and other building products. Legacy substances used in PVC products, like lead, cadmium, and phthalates, are turning up in new products through the use of cheap recycled content.

Funding for research on post-consumer PVC feedstock was provided by StopWaste and donors to the Healthy Building Network (HBN). It was conducted using an evaluative framework to optimize recycling developed by StopWaste, the San Francisco Department of the Environment, and HBN. This briefing paper on post-consumer recycled PVC is a prequel to a forthcoming white paper by this new collaboration.

Source separation of waste streams and toxic content restrictions are crucial actions toward optimizing the value of recycled feedstocks in building products. HBN’s research on glass waste – known as cullet – reveals the multitude of economic and environmental benefits of these practices.

The ability of fiber glass insulation manufacturers to incorporate cullet increases; the wasteful landfilling of discarded glass (nationally, only 28% is recycled) decreases. Manufacturers need less energy to produce insulation, leading to lower greenhouse gas emissions. Workers, surrounding neighborhoods, and the environment at large are exposed to fewer toxic contaminants. Post-Consumer Cullet in California is the second in a series of Healthy Building Network reports for the Optimizing Recycling collaboration.

Health

Health Climate Change

Climate Change Pollution

Pollution