READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

What do building materials have to do with social justice? Learn more in this article by Diana Alley, Avideh Haghighi, and Lona Rerickat at ZGF Architects.

Health Care Without Harm Europe advocates for the complete elimination of PVC due to its environmental impact, urging policymakers to develop a strategy for its phase-out in Europe.

If we are to have any chance of addressing the global plastics crisis, Polyvinyl Chloride plastic (PVC) also known as vinyl, has got to go.

It cannot be produced sustainably or equitably. It cannot be “optimized.” It cannot be recycled. It will never find a place in a circular economy, and it makes it harder to achieve circularity with other materials, including other plastics.

There are three reasons for this: technical, economic, and behavioral. The inherent qualities of PVC and its cousin, CPVC, make it among the most technologically challenging plastics to recycle. Like most plastics, PVC is made with fossil fuel feedstocks. Unlike other plastics, PVC/vinyl also contains substantial amounts of chlorine, upwards of 40%. This is the C in PVC, and this chlorine content adds an additional layer of negative impacts to the earth and its people, social inequity, and an impediment to recycling that cannot be overcome. Recyclers consider it a contaminant to other plastic feedstock streams.1 It mucks up the machines and the already perilous economics of plastics recycling.

There is an emerging global consensus on this point, albeit euphemistically stated. The Ellen MacArthur New Plastics Economy Project consists of representatives from the world’s largest plastic makers and users, along with governments, academics, and NGOs. In 2017 it reached the conclusion that PVC was an “uncommon” plastic that was unlikely to be recycled and should be avoided in favor of other more recyclable packaging materials.2 “Uncommon” in the diplomatic parlance of international multistakeholder initiatives means unrecyclable. The project also took note of the many toxic emissions associated with PVC production.

That’s not surprising since after 30 years of hollow promises and pilot projects doomed to fail, virtually no post-consumer PVC is recycled.3 Conversely, leading brands with forward-looking materials policies such such as Nike, Apple, and Google have prioritized PVC phase outs.4

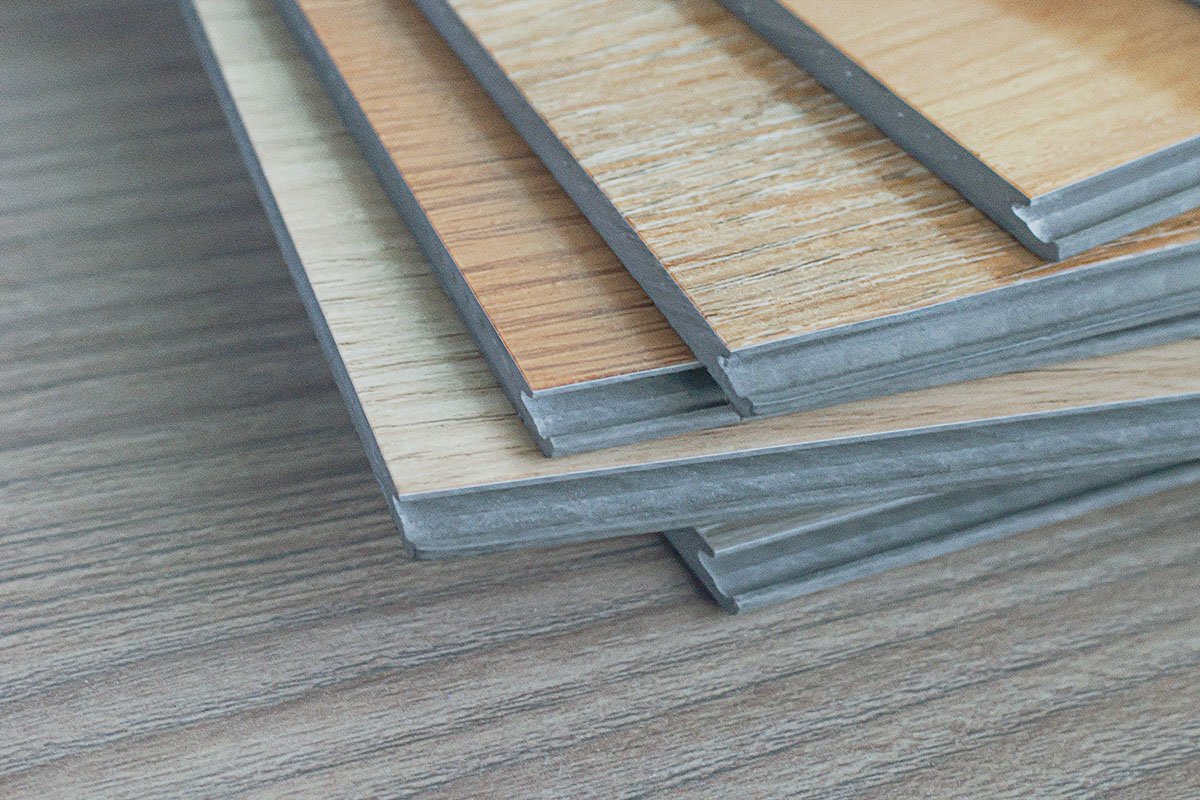

But in the building industry, PVC rages on. Virgin vinyl LVT flooring is the fastest growing product in the flooring sector. So much so that in 2017 sustainability leader Interface introduced a new product line of virgin vinyl LVT, despite forecasting just one year before that by 2020 the company would “source 95 percent of its materials from recycled or biobased resources.”5

The current flooring market demands the impossible – aesthetic qualities and durability at a price unmatchable by non-vinyl floor coverings. A price that is unmatchable because at every stage of vinyl production, the societal costs of its poisonous environmental health consequences are externalized, subsidized, paid for by the people who live in communities that have become virtual poster children for environmental injustice and oppression. Places like Mossville, LA; Freeport, TX; and the Xinjiang Province in China, home to the oppressed Uighur population. As we detail in our exhaustive Chlorine and Building Materials report, the unique chlorine component of PVC plastic contributes to a range of toxic pollution problems starting with the fact that chlorine production relies upon either mercury-, asbestos-, or PFAS-based processes. This is in addition to the onerous environmental health burdens of petrochemical processing that burden all plastics.

It is true that all plastics contribute to environmental injustices. Virtually all plastics are made from fossil fuel feedstocks, and all plastics share abysmally low recovery and cycling rates. Still, independent experts agree that some plastics are worse than others, and PVC is among the worst.6 Additionally, most uses of PVC have readily available alternatives or solutions that are within reach. Certainly there are non-PVC alternatives for flooring. What can’t be beat is the cost – that is, the low purchase price at the point of sale, subsidized by the sacrifices we ignore in the communities where the plastics are manufactured and the waste is dealt with. And BIPOC communities bear the disproportionate burden of it all. Acknowledging and addressing this tradeoff is at the root of the behavioral change that stands between us and a just and healthy circular economy.

In his influential book How To Be An Antiracist, Dr. Ibram X. Kendi argues that if we recognize we live in a society with many racial inequities – and acknowledge that since no racial group is inferior or superior to another, the cause of these inequities are policies and practices – then to be anti-racist is to challenge those policies and practices where we can and create new ones that create equity and justice for all.

Imagine if as part of our commitment to equity in our sustainability efforts, we recognized, acknowledged, and did what we could to address the racial inequities associated with PVC production, and committed right now to stop using PVC unless it was absolutely essential. The plastics industry would howl and point out inconsistencies, question priorities, highlight unintended consequences. We would all feel a tinge of whataboutism – what about carbon, or this other injustice, or that shortcoming of the alternatives. But it is clear that widespread incrementalism is failing us on so many fronts, none more than the environmental injustices that are hardwired into our supply chains.

In fact, there are many examples of companies and building projects that have prioritized PVC-free alternatives based upon principles of equity and justice. We need more leaders in the field to join those who are abandoning vinyl in product types that have superior options. Our CEO Gina Ciganik used a non-PVC flooring in 2015 at The Rose, her last development project prior to joining HBN.

First Community Housing, another affordable housing leader, has been using linoleum for many years for similar reasons. In their Leigh Avenue Apartments project. Forbo’s Marmoleum Click tiles were the flooring of choice.

Vinyl is not an essential material for any of the largest surface areas of our building projects – flooring, wall coverings, or roofing. It may often be the conventional choice in conventional buildings, but it should not be the conventional choice in buildings that promise to be green, healthy, and equitable. LVT may be the fastest growing flooring product in the world, but it is a throwback to the inequitable, unsustainable world we say is unacceptable, not the world we are trying to create.

Habitable can help you start by using our Informed™ product guidance, which helps identify worst and best in class products that are healthier for people and the planet. So why not start here and now, with a principled stand of refusing to profit from unjust, frequently racist, externalized costs?

SOURCES

- https://plasticsrecycling.org/pvc-design-guidance

- See pp. 27-29: www.newplasticseconomy.org/assets/doc/New-Plastics-Economy_Catalysing-Action_13-1-17.pdf

- See e.g. Figure 1: https://css.umich.edu/publication/plastics-us-toward-material-flow-characterization-production-markets-and-end-life

- See e.g.: www.apple.com/environment/answers (Apple); www.greenpeace.org/usa/reports/greener-electronics-2017 (Google); www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-aug-26-fi-16540-story.html (Nike)

- www.greenbiz.com/article/inside-interfaces-bold-new-mission-achieve-climate-take-back: “Going Beyond Zero” The march towards Mission Zero continued unabated, however, with consistent year-over-year improvement in most metrics. Today, the company forecasts that by 2020 it will halve its energy use, power 87 percent of its operations with renewable energy, cut water intake by 90 percent, reduce greenhouse gas emissions 95 percent (and its overall carbon footprint by 80 percent), send nothing to landfills, and source 95 percent of its materials from recycled or biobased resources.

- www.cleanproduction.org/resources/entry/plastics-scorecard-press-release

Phase 2 of this report is the first of its kind plant-by-plant accounting of the production, use, and releases of chlorine and related pollution around the world. It is intended to inform the efforts of building product manufacturers to reduce pollution in their supply chains.

Chlorine is a key feedstock for a wide range of chemicals and consumer products, and the major ingredient of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic. The report includes details aboutthe production technologies used and markets served by 146 chlor-alkali plants (60 in Asia) and which of these plants supply chlorine to 113 PVC plants (52 in Asia). The report answers fundamental questions like:

- Who is producing chlorine?

- Who is producing PVC?

- Where? How much? And with what technologies?

- What products use the chlorine made in each plant?

Key findings include:

- Over half of the world’s chlorine is consumed in the production of PVC. In China, we estimate that 74 percent of chlorine is used to make PVC.

- 94 percent of plants in Asia covered in this report use PFAS-coated membrane technology to generate chlorine.

- In Asia the PVC industry has traded one form of mercury use for another. While use of mercury cell in chlorine production is declining, the use of mercury catalysts in PVC production via the acetylene route is on the rise. 63 percent of PVC plants in Asia use the acetylene route.

- 100 percent of the PVC supply chain depends upon at least one form of toxic technology. These include mercury cells, diaphragms coated with asbestos, or membranes coated with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), used in chlorine production. In PVC production, especially in China, toxic technologies include the use of mercury catalysts.

Supplemental Documents:

For years, Habitable has been thinking about and consulting with our partners about how to describe the impact of choosing healthier building products. Here’s why this is a complex and challenging issue for the industry:

- Incomplete knowledge of what many building products are made of

- Limited understanding of the health hazards of the thousands of chemicals in commerce today

- Trade-offs when making material choices

These reasons drive the need for full transparency of chemical contents and full assessment of chemical hazards. This can ultimately lead to optimizing products in order to avoid hazardous chemicals.

Toxic chemicals have a huge and complex impact on the health and well-being of people and the environment. Those impacts are spread throughout a product’s life cycle. For example, fenceline communities can be exposed during the manufacturing of products in adjacent facilities, workers can be exposed on the job during the manufacturing and installation processes, and building occupants can be exposed during the product’s use stage. Some individuals suffer multiple exposures because they are affected in all of those instances.

In addition, toxic chemicals can be released when materials are disposed of or recycled. When they incorporate recycled content into new products, manufacturers can include legacy toxicants, inhibiting the circular economy and exposing individuals to hazardous chemicals—even those that have been phased out as intentional content in products.

We know intrinsically that hazardous chemicals have the potential to do harm and that they commonly do so. For champions of this cause, that understanding of the precautionary principle is enough. Others still need to be convinced and often want to quantify the impact of a healthy materials program. How can healthy building champions start to talk about and quantify the impacts of material choices?

Broad Impacts of Toxic Chemicals

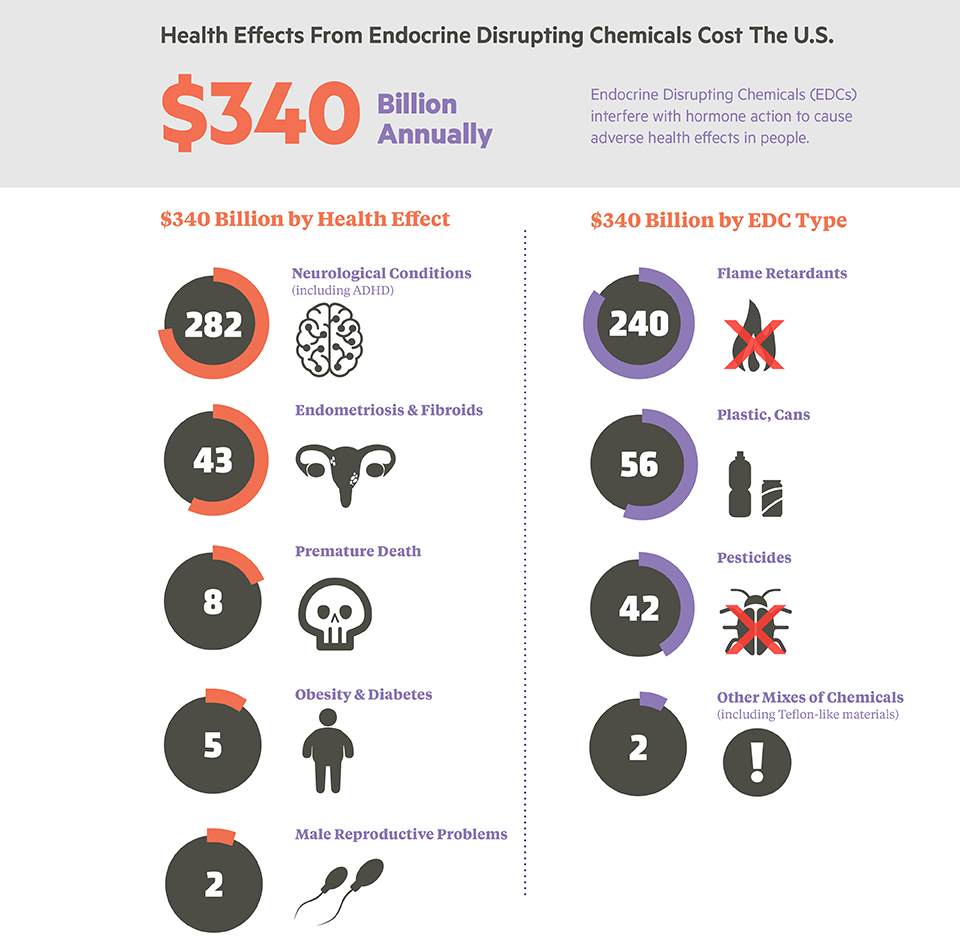

One way researchers quantify the impact of chemicals is to consider the broad economic impacts of chemical exposures. Evidence increasingly shows that toxic chemical exposures may be costing the USA billions of dollars and millions of IQ points. One recent study estimates that certain endocrine-disrupting chemicals cost the United States $340 billion each year. This is a staggerring 2.3% of the US gross domestic product.1 And that is for only a subset of the hazardous chemicals that surround us every day. These numbers provide important context for the larger discussion of toxic chemical use, but cannot easily be tied to daily decisions about specific materials.

Market Scale Impacts

For years, Habitable has been targeting orthophthalates in vinyl flooring as a key chemical and product category combination to be avoided. Orthophthalates can be released from products and deposited in dust which can be inhaled or ingested by residents—particularly young children who crawl on floors and often place their hands in their mouths3. By systematically reducing chemicals of concern in common products, we can all work together to continue to affect this scale of change in the marketplace and keep millions more tons of hazardous chemicals out of buildings.

Impacts on the Project Scale

Context is key for understanding the impact chemical reduction or elimination can have—a pound of one chemical may not have the same level of impact as a pound of another chemical. But, given the right context, this sort of calculation may prove useful as part of a larger story. The following examples provide context for the story of different impacts of different chemicals.

- Small decisions, big impacts: While many manufacturers and retailers have phased out hazardous orthophthalate plasticizers, some vinyl flooring may still contain them. If we consider an example affordable housing project, avoiding orthophthalates in flooring can keep dozens of pounds of these hazardous chemicals out of a single unit (about the equivalent of 10 gallons of milk).4 For a whole building, this equates to several tons of orthophthalates that can be avoided.5 It is easy to see how this impact quickly magnifies in the context of a broader market shift.

- Little things matter: Alkylphenol ethoxylates (APEs) in paints are endocrine-disrupting chemicals make up less than one percent of a typical paint. In this case, by making the choice to avoid APEs, a couple of pounds of these hazardous chemicals are kept out of a single unit (about the equivalent of a quart of milk). This translates to a couple of hundred pounds kept out of an entire building.6 This quantity may seem small compared to the tons avoided in the phthalate example above, but little things matter. Small exposures to chemicals can have big impacts, particularly for developing children.7 And, since our environments can contain many hazardous chemicals, and we aren’t exposed to just a single chemical at a time, these exposures stack up in our bodies.8

- Reducing exposure everywhere: Choosing products without hazardous target chemicals keeps them out of buildings, but can also reduce exposures as these products are manufactured, installed, and disposed of or recycled. Some chemicals may have impacts that occur primarily outside of the residence where they are installed, but these impacts can still be significant. Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), for example, a primary component of vinyl flooring, requires toxic processes for its production and can generate toxic pollution when it is disposed of. Manufacturing of the PVC needed to create the vinyl flooring for one building as described above can release dozens of pounds of hazardous chlorinated emissions, impacting air quality in surrounding communities.9 These fenceline communities are often low-income, and suffer from disproportionate exposure in their homes, through their work, and from local air pollution. If choosing non-vinyl flooring for a single building can help reduce potential exposure to hazardous chlorinated emissions in these fenceline communities, imagine the potential impacts of avoiding vinyl on a larger scale!

In addition to information about target chemicals to avoid, our Informed™ product guidance provides recommendations of alternative types of materials that are typically better from a health hazard perspective and includes steps to work toward the goal of full transparency of product content and full assessment of chemical hazards. This framework can help ensure that toxic chemicals and regrettable substitutions are avoided.

Each decision you make about the materials you use, each step toward using healthier products, can have big impacts within a housing unit, a building, and in the broader environment. Collectively, these individual decisions also influence manufacturers to provide better, more transparent products for us all. Ultimately, this can reduce the hazardous chemicals not just in our buildings but also in our bodies.

SOURCES

- Attina, Teresa M, Russ Hauser, Sheela Sathyanaraya, Patricia A Hunt, Jean-Pierre Bourguignon, John Peterson Myers, Joseph DiGangi, R Thomas Zoeller, and Leonardo Trasande. “Exposure to Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in the USA: A Population-Based Disease Burden and Cost Analysis.” The Lancet 4, no. 12 (December 1, 2016): 996–1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30275-3.

- “Disease Burden & Costs Due to Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals.” NYU Langone Health, July 12, 2019. https://med.nyu.edu/departments-institutes/pediatrics/divisions/environmental-pediatrics/research/policy-initiatives/disease-burden-costs-endocrine-disrupting-chemicals.

- Bi, Chenyang, Juan P. Maestre, LiG Hongwan, GeR Zhang, Raheleh Givehchi, Alireza Mahdavi, Kerry A. Kinney, Jeffery Siegel, Sharon D. Horner, and Ying Xu. “Phthalates and Organophosphates in Settled Dust and HVAC Filter Dust of U.S. Low-Income Homes: Association with Season, Building Characteristics, and Childhood Asthma.” Environment International 121 (December 2018): 916–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.09.013.; Mitro, Susanna D., Robin E. Dodson, Veena Singla, Gary Adamkiewicz, Angelo F. Elmi, Monica K. Tilly, and Ami R. Zota. “Consumer Product Chemicals in Indoor Dust: A Quantitative Meta-Analysis of U.S. Studies.” Environmental Science & Technology 50, no. 19 (October 4, 2016): 10661–72. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b02023.

- According to the USDA, milk typically weighs about 8.6 pounds per gallon. See: “Weights, Measures, and Conversion Factors for Agricultural Commodities and Their Products.” United States Department of Agriculture, June 1992. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/41880/33132_ah697_002.pdf?v=0.

- HBN used the Common Products for Luxury Vinyl Tile and Vinyl Sheet to estimate the amount of plasticizer. We assumed a 100 unit building of 1000 square foot two-bedroom apartments with vinyl flooring throughout the units.

- HBN used the Common Product profiles for Eggshell and Flat Paint to estimate the amount of surfactant and assumed a 100 unit building of 1000 square foot two-bedroom apartments.

- Vandenberg, Laura N., Theo Colborn, Tyrone B. Hayes, Jerrold J. Heindel, David R. Jacobs, Duk-Hee Lee, Toshi Shioda, et al. “Hormones and Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: Low-Dose Effects and Nonmonotonic Dose Responses.” Endocrine Reviews 33, no. 3 (June 1, 2012): 378–455. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2011-1050.

- Impacts can be additive, where health impacts are equal to the sum of the effect of each chemical alone. They can also be synergistic, where the resulting health impacts are greater than the sum of the individual chemicals’ expected impacts.

- HBN used the Common Products for Luxury Vinyl Tile and Vinyl Sheet to estimate the amount of PVC. We assumed a 100 unit building of 1000 square foot two-bedroom apartments with vinyl flooring throughout the units. Emissions are based on the Calvert City, KY Westlake plant examined in HBN’s Chlorine and Building Materials Project. According to EPA’s EJScreen tool, the census blockgroup where this facility is located is primarily low income, with 62% of the population considered low income (putting this census block group in the 88th percentile nationwide in terms of low income population). EJScreen, EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool (Version 2018). Accessed March 18, 2019. https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/.

Discover how bisphenols and phthalates, commonly used in plastics for added strength or flexibility, can disrupt hormone function, and learn ways to reduce their use for improved health in this informative video.

Phase 1 of this report is the first of its kind plant-by-plant accounting of the production, use, and releases of chlorine and related pollution around the world. It is intended to inform the efforts of building product manufacturers to reduce pollution in their supply chains.

Chlorine is a key feedstock for a wide range of chemicals and consumer products, and the major ingredient of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic. The report includes details about the largest 86 chlor-alkali facilities and reveals their connections to 56 PVC resin plants in the Americas, Africa and Europe. (The second phase of this project will inventory the industry in Asia.) A substantial number of these facilities, which are identified in the report, continue to use outmoded and highly polluting mercury or asbestos.

Demand from manufacturers of building and construction products now drives the production of chlorine, the key ingredient of PVC used in pipes, siding, roofing membranes, wall covering, flooring, and carpeting. It is also an essential feedstock for epoxies used in adhesives and flooring topcoats, and for polyurethane used in insulation and flooring.

Key findings include:

- In the United States, the chlor-alkali industry is the only industry that still uses asbestos, importing 480 tons per year on average for 11 chlor-alkali plants in the country (including 7 of the 12 largest plants).

- The only suppliers of asbestos to the chlor-alkali industry are Brazil (which banned its production, although exports continue for the moment) and Russia, whose Uralasbest mine is poised to become the sole source of asbestos once Brazil’s ban is in place.

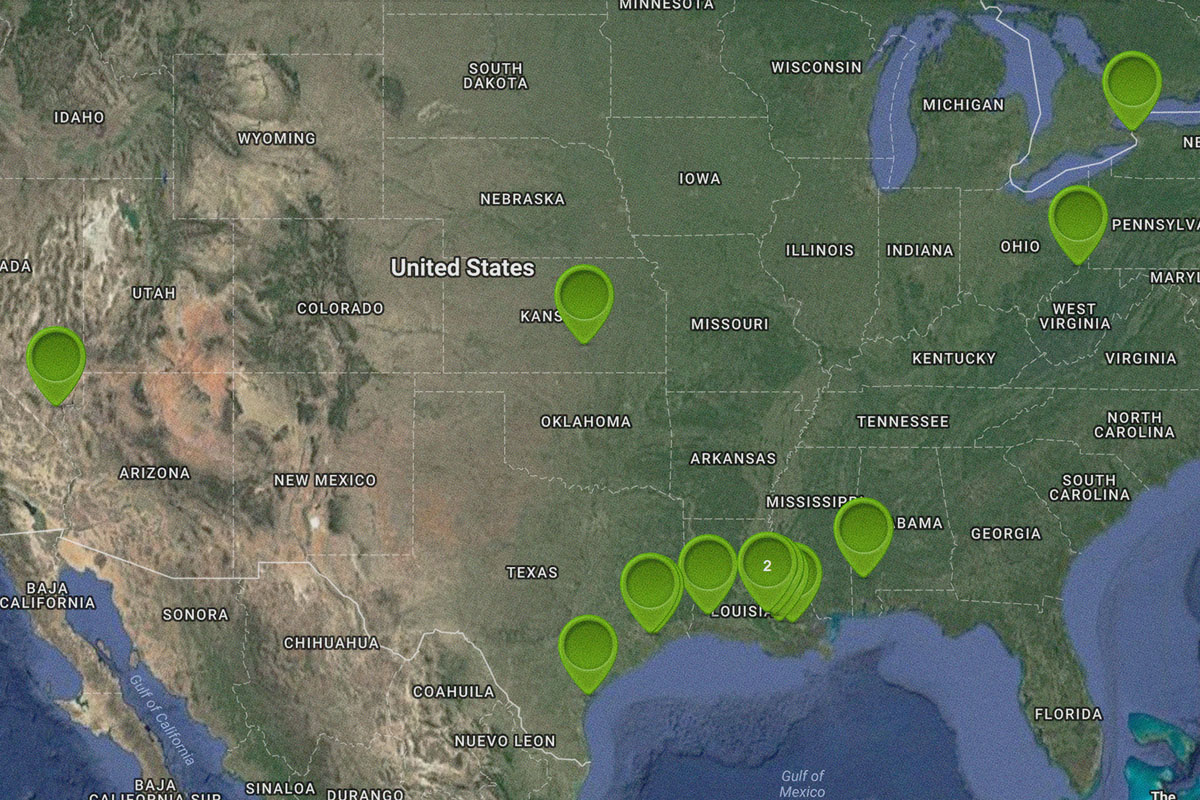

- The US Gulf Coast is the world’s lowest-cost region for production of chlorine and its derivatives. It is home to 9 facilities that use asbestos technology, and some of the industry’s worst polluters including 5 of the 6 largest emitters of dioxin.

- One Gulf Coast facility has been found responsible for chronic releases of PVC plastic pellets into the Gulf of Mexico watershed.

- The US, Russia and Germany are the only countries in this report that allow the indefinite use of both mercury and asbestos in chlorine production.

- The world’s two largest chemical corporations – BASF and DowDuPont – have not announced any plans to phase out the use of mercury and asbestos, respectively, at their plants in Germany.

- Chlor-alkali facilities are major sources of rising levels of carbon tetrachloride, a potent global warming and ozone depleting gas, in the earth’s atmosphere.

- Far more chlorinated pollution, such as dioxins and vinyl chloride monomer, is released from chlor-alkali plants that produce feedstocks for the PVC industry than from plants that produce chlorine for other uses.

Supplemental Documents:

While attending a 2018 meeting of U.S. EPA’s National Environmental Justice Advisory Council (NEJAC) in Boston, I heard the testimony of Delma and Christine Bennet. They live in Mossville, LA, amidst what is likely the nation’s largest concentration of PVC (polyvinyl chloride) manufacturing facilities. I was there to present the findings of HBN’s inventory of pollution associated with the chlorine/PVC supply chain.

Our study found, among other things, that the Gulf Coast region (which includes Mossville) is home to nine facilities that use outmoded asbestos technology, and home also to some of the industry’s worst polluters: Five of the six largest emitters of dioxins––a long lasting, extremely toxic family of hazardous waste that causes cancer and many other health impacts, are located there. The Bennets reminded the EPA that according to studies by a division of the Centers for Disease Control, Mossville residents have three times higher levels of dioxin in their blood than average Americans, and the dioxin levels found in their yards and attic dust exceed regulatory standards typically used for toxic waste remediations of industrial sites. Even the vegetables in their gardens tested positive for dioxin.

When I think about why we fight so hard to exclude PVC from any palette of green, healthy, or sustainable building materials, I think first of people like Delma and Christine. I then think about the many non-profits, government agencies, and private enterprises dedicated to recycling. Way back in the 1990’s, the industry Association of Plastic Recyclers declared PVC a contaminant to the recycling stream. A generation later, a 2016 study by the Circular Economy evangelist Ellen MacArthur Foundation called out PVC packaging for global phase-out, citing low recycling rates and chemical hazard concerns. Much of the concern about PVC packaging is driven by worries about ocean pollution. HBN’s study found that at least one U.S. PVC manufacturer is routinely dumping tons of PVC pellets into local waterways and refusing to stop even after being ordered to do so by the state of Texas.

The list goes on. Our report documents the types of industrial pollution in addition to dioxin that could be reduced or avoided by a switch to more recyclable plastics that are not made with the chlorine that is an essential ingredient of PVC, including ozone depleting and potent global warming gasses. HBN’s earlier studies have documented the hazards posed by legacy pollutants that are returning to our consumer products in recycled PVC content––heavy metals such as lead, and endocrine-disrupting plasticizers known as phthalates.

There is a better way.

There is virtually no use of PVC in building products that could not be replaced with another plastic or other material. Indeed, from siding, to wallpaper, to window frames, PVC has displaced materials that are more recyclable, such as aluminum and paper. Because the industry is not held accountable for the environmental health damages wrought in places like Mossville, PVC has artificially low costs that present barriers to entry, or inhibit market expansion of less hazardous, more sustainable alternatives.

That is why PVC should not be part of any building, or any building rating system, that claims to advance environmental and health objectives. It’s not green. It’s not healthy. It’s not sustainable. It’s just cheap––for us. Because folks like Delma and Christine Bennet pay the true cost.

Know Better

Learn more about the implications of chlorine as a feedstock in plastics in HBN’s Chlorine and Building Materials report.

Research from Healthy Building Network (HBN) documents how vinyl building products, also known as PVC or polyvinylchloride plastic, are the number one driver of asbestos use in the US.

The vinyl/asbestos connection stems from the fact that PVC production is the largest single use for industrial chlorine, and chlorine production is the largest single consumer of asbestos in the US. [1] More than 70% of PVC is used in building and construction applications – pipes, flooring, window frames, siding, wall coverings and membrane roofing. [2] This makes the building and construction industry the single largest product sector consuming chlorine, bearing sizeable responsibility for the ongoing demand for asbestos. [3]

Despite the existence of asbestos (and mercury) free chlorine production methods, the PVC industry has positioned itself at the vanguard of industry efforts to frustrate stronger asbestos regulation. According to Mike Belliveau, the Executive Director of the Environmental Health Strategy Center and a senior advisor to Safer Chemicals Healthy Families coalition, “The PVC market has spurred chemical industry lobbyists to urge the Trump Administration to exempt their use of deadly asbestos from future restrictions.” The last time the vinyl industry positioned themselves so publicly on the other side of common sense, they were defending the use of lead in children’s vinyl lunch boxes.

Among HBN’s Findings:

- The U.S. chlor-alkali industry (Olin/Dow, Occidental, and Westlake/Axiall [4]) consumed 88% of asbestos imports in 2014, and all asbestos imports in 2016.

- Three U.S. chemical companies are importing 1.2 million pounds of asbestos per year for use in 15 chlor-alkali plants. PVC used in building products requires an estimated 250,000 pounds of imported asbestos per year.

- Asbestos miners in Minaçu, Brazil, are literally dying to prop up the U.S. chemical and PVC building product industries’ reliance on asbestos. Dozens of asbestos baggers are dying or have died of asbestos related diseases, according to local reports. [5] Overall, Brazil exports over 13,000 bags of asbestos each year to the U.S. chlorine industry.

- Occidental Chemical imported 900,000 pounds of asbestos from Oct. 2013 through 2015, but apparently failed to report those imports to the EPA in possible violation of the Chemical Data Reporting rule as required under TSCA.

- Asbestos imports by Occidental Chemical and Olin Corporation more than doubled from 2015 to 2016, perhaps indicating a stockpiling of asbestos in anticipation of further restrictions on mining in Brazil or use in the U.S.

- Russia shipped asbestos to Dow in 2014 and to Olin in 2016 (when Olin took over Dow’s U.S. chlor-alkali plants). If the mine in Brazil closes, the U.S. chlor-alkali industry’s backup plan is the massive mine in Asbest, Russia.

The health hazards of asbestos exposure, painful and deadly lung diseases including cancer, are clear. Green building professionals do not have to wait. Do your part to prevent asbestos-related diseases here and abroad. Don’t specify vinyl building products.

SOURCES

1. In the US more than half of chlorine is produced using asbestos, despite the availability of an alternative production method that does not require either asbestos or mercury.

2. http://www.vinylinfo.org/vinyl/uses

3. According to IHS Markit, “A majority of chlor-alkali capacity is built to supply feedstock for ethylene dichloride (EDC) production. EDC is then used to make vinyl chloride (VCM) and subsequently used to manufacture polyvinyl chloride (PVC). This chain, EDC to VCM to PVC, is normally called the vinyl chain. PVC demand correlates closely with construction spending, therefore, it can be concluded that chlorine consumption and production are driven by the construction industry. Hence, chlorine consumption growth depends on the growth of the global economy, since a country will spend more on construction if it has a healthy gross domestic product.” (IHS Markit. “Chemical Economics Handbook: Chlorine/Sodium Hydroxide (Chlor-Alkali),” December 2014. https://www.ihs.com/products/chlorine-sodium-chemical-economics-handbook.html)

4. Fifteen chlor-alkali plants last reported to be using asbestos diaphragms include, in order of estimated chlorine capacity:

-

- Olin (formerly Dow), Freeport, Tex. (3,158,000 tons per year)

- Westlake (formerly Axiall), Lake Charles, La. (1,100,000 tpy)

- Olin, Plaquemine, La. (1,068,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Ingleside/Corpus Christi, Tex. (668,000 tpy)

- Occidental, La Porte, Tex. (580,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Hahnville/Taft, La. (567,000 tpy)

- Olin, McIntosh, Ala. (468,000 tpy)

- Westlake, Plaquemine, La. (410,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Convent, La. (389,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Niagara Falls, N.Y. (336,000 tpy)

- Westlake, Natrium/New Martinsville, W.Va. (297,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Geismar, La. (273,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Wichita, Kans. (182,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Deer Park, Tex. (162,500 tpy)

- Olin, Henderson, Nev. (153,000 tpy)

5. Carpentier, Steve. “Minaçu, a cidade que respira o amianto.” CartaCapital, May 21, 2013. http://www.cartacapital.com.br/sustentabilidade/minacu-a-cidade-que-respira-o-amianto-8717.html

The recycling industry has made significant strides toward a closed loop material system in which the materials that make up new products today will become the raw material used to manufacture products in the future. However, contamination in some sources of recycled content raw material (“feedstock”) contain potentially toxic substances that can devalue feedstocks, impede growth of recycling markets, and harm human and environmental health.

Since May 2014, the Healthy Building Network, in collaboration with StopWaste and the San Francisco Department of Environment, has been evaluating 11 common post-consumer recycled-content feedstocks used in the manufacturing of building products. This paper is a distillation of that larger effort, and provides analysis on two major feedstocks found in building products: recycled PVC and glass cullet. This research partnership seeks to provide manufacturers, purchasers, government agencies, and the recycling industry with recommendations for optimizing the use of recycled content feedstocks in building products in order to increase their value, marketability and safety. This report was prepared in support of a research session at the 2015 Greenbuild conference in Washington, DC.

Equity

Equity Pollution

Pollution Health

Health