READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT“When I came here, my unit was on the brink of falling apart. We had so many problems; the carpets were incredibly old, and turning the AC on was like having a helicopter inside the house.”

These are the words of Vanessa del Campo. She was born and raised in Mexico and like many other people, she moved to the United States searching for safer and better living conditions. She now lives in Minnesota and rents a small unit in a multifamily apartment building located in one of the areas designated by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) as of Environmental Justice concern. Her experience as a tenant is filled with stories of unjust evictions, health concerns, and constant battles with unlawful landlords that neglected her right to even the most basic human living conditions.

Fortunately for Vanessa and other neighbors in her building, she received support from a community-based organization, Renters United for Justice (abbreviated IX from its name in Spanish), that helped them organize and mobilize to reclaim desperately needed services to maintain their health and wellbeing. What began as an organized effort to request new windows for a handful of apartment units turned into an exhausting but successful journey to purchase the run-down complex of apartment buildings from their landlord and secure a loan to renovate all the apartments.

It’s easy to get lost in Vanessa’s excitement as she talks about this newfound opportunity. She mentioned that her baby had a tough time learning to crawl because it was too dangerous to place her on the ground due to rats and cockroaches often running past her. At the same time, it is also easy to forget that in addition to being a mother and having a demanding job, she now has to fulfill the role of a building co-owner as a leading member of the newly formed residents’ collective (A Sky Without Limits).

With so much work going into buying and renovating the apartment complex, the residents had little time to think about the chemical safety of their chosen building materials. That’s where HBN came in. In 2021 the MPCA awarded IX and Healthy Building Network a grant to work together to reduce toxic chemical exposures among children, pregnant individuals, employees, and communities who are disproportionately impacted by harmful chemicals used in common products.

One example of toxic chemicals in homes are phthalates, or orthophthalates, which are chemicals that help make plastics flexible. They can also impact the proper development of children. These chemicals are banned in children’s toys in the U.S., and The Minnesota Department of Health in partnership with MPCA named phthalates as “Priority Chemicals” as part of the 2017 Toxic-Free Kids Act. While many manufacturers have phased out hazardous phthalate plasticizers, existing vinyl flooring, especially those installed 2015 and earlier, likely contain these potential developmental toxicants. This translates to dozens of pounds of these hazardous chemicals in the floor of a single apartment unit. As these chemicals are released from products, they deposit in dust, which can be inhaled or ingested by residents – particularly young children who are crawling on floors and often place their hands in their mouths.

“Honestly, we never stopped to think about how harmful [building] materials could be.” Vanessa said. “It was just regrettable to see how we were living. We understand that the new materials that are going into our buildings today may not be the healthiest. Today, we realize it is important to think about how we want to live in our homes, to imagine the quality of life we want in our buildings, in our community.”

Over the coming year, HBN will work with IX and the residents’ collective to evaluate the materials used in their ongoing renovation process and provide recommendations to improve material selection. We will also develop resources tailored to residents to enhance their understanding of how the surrounding environment influences their health. To extend the impact of this work, we will create and share a set of best practices that property managers and tenant organizations can use to advocate for healthier materials in the communities they live in and properties they manage.

“Our collaboration with HBN is timely. By working together with the property managers, we can raise their awareness about how their work impacts our health and help change how they select materials,” Vanessa said.

At Healthy Building Network, we are grateful for the opportunity to work with IX and local leaders like Vanessa through the MPCA grant that makes this collaboration possible. We call on public agencies, foundations, and private investors to fund initiatives that seek to dismantle health inequities through direct investment in the communities disproportionately impacted by environmental injustice, especially related to toxic chemical exposures. We look forward to sharing with you the lessons, stories, and resources that come out of this collaboration.

To learn more about selecting healthier products, visit our Informed™ website, which includes a wide range of resources and tools to help you find healthier material options.

Un inquilino clama por viviendas más seguras y saludables

“Cuando llegué aquí, mi apartamento estaba a punto de desmoronarse. Tuvimos muchos problemas; las alfombras eran increíblemente viejas y encender el aire acondicionado era como tener un helicóptero dentro de la casa”. Estas son las palabras de Vanessa del Campo.

Vanessa nació y creció en México, y como muchas otras personas, se mudó a los Estados Unidos en busca de mejores condiciones de vida. Ahora vive en Minnesota y alquila un apartamento en un edificio multifamiliar ubicado en una de las áreas designadas por la Agencia de Control de Contaminación de Minnesota (MPCA) como de interés de Justicia Ambiental. Su experiencia como inquilina está marcada con historias de desalojos injustos, preocupaciones de salud, y batallas constantes con propietarios que negaron su derecho a incluso las condiciones más básicas de vida.

Afortunadamente para Vanessa y otros vecinos en su edificio, ella recibió el apoyo de Inquilinos Unidos por Justicia (IX), una organización comunitaria que les ayudó a organizarse y movilizarse para recuperar los servicios que desesperadamente necesitaban para mantener su salud y bienestar. Lo que comenzó como un esfuerzo organizado para solicitar nuevas ventanas para un pequeño número de apartamentos, se convirtió en una larga pero exitosa tarea para comprar el destartalado complejo de apartamentos y asegurar un préstamo para renovar todas sus unidades.

“Pasamos por muchos litigios con el propietario porque no estaba haciendo las reparaciones que necesitábamos y no quería vendernos los edificios. El año pasado, cuando llegó la pandemia, finalmente obtuvimos la oportunidad de comprar el edificio. Fue un momento feliz y difícil porque estábamos aterrorizados de enfermarnos [con el virus], pero logramos organizarnos y apoyarnos unos a otros. Hoy estamos trabajando con una nueva empresa de administración de propiedades y el banco para instalar alfombras, pisos, techos, ventanas, hornos, refrigeradores y baños nuevos. Estamos haciendo una profunda renovación para llevar todos los apartamentos a un estado que es mucho, mucho mejor que el que teníamos”.

Es fácil dejarse llevar por la emoción de Vanessa mientras habla de esta nueva oportunidad. Ella mencionó que su bebé tuvo dificultades para aprender a gatear porque era demasiado peligroso colocarle en el suelo debido a las ratas y cucarachas que a menudo rondaban la casa. Al mismo tiempo, también es fácil olvidar que además de ser madre y tener un trabajo exigente, ahora tiene que cumplir el rol de copropietaria de un edificio como miembro principal de un recién formado colectivo de residentes (Un Cielo Sin Límites).

Con tanto trabajo invertido en la compra y renovación del complejo de apartamentos, los residentes tuvieron poco tiempo para pensar en la seguridad química de los materiales de construcción que fueron utilizados en sus apartamentos. Ahí es donde entra Healthy Building Network (HBN, o, La Red de Edificios Saludables). A principios de este año, MPCA otorgó a IX y HBN una subvención para reducir la exposición a sustancias químicas tóxicas entre los niños, las personas embarazadas, los empleados y las comunidades que se ven afectadas de manera desproporcionada por sustancias químicas nocivas utilizadas en productos comunes.

Un ejemplo de sustancias químicas tóxicas en los hogares son los ftalatos u ortoftalatos, que son sustancias químicas utilizadas para ayudar a dar flexibilizar a los plásticos. Estas sustancias también pueden afectar el desarrollo adecuado de los niños. Estos productos químicos están prohibidos en los juguetes de los niños en los EE. UU. El Departamento de Salud de Minnesota, en asociación con MPCA, nombró a los ftalatos como “productos químicos prioritarios” como parte de la Ley de Niños Libres de Tóxicos de 2017. Si bien muchos fabricantes han eliminado los plastificantes de ftalato, estos químicos están presentes en los pisos de vinilo existentes, especialmente los instalados antes de 2016. Esto se traduce en docenas de libras de estos químicos peligrosos en el piso de una sola unidad de apartamento. A medida que estos productos químicos se liberan de los productos, se depositan en el polvo que los residentes pueden inhalar o ingerir, afectando especialmente a los niños pequeños que gatean por el suelo y a menudo se llevan las manos a la boca.

“Honestamente, nunca nos detuvimos a pensar en lo dañino que podrían ser los materiales [de construcción]”. Dijo Vanessa. “Fue lamentable ver cómo vivíamos. Entendemos que los materiales que se utilizan en nuestros edificios hoy en día pueden no ser los más saludables. Hoy nos damos cuenta de que es importante pensar en cómo queremos vivir en nuestros hogares, imaginar la calidad de vida que queremos en nuestros edificios, en nuestra comunidad”.

Durante el próximo año, HBN trabajará con IX y el colectivo de residentes para evaluar los materiales utilizados en su proceso de renovación y brindar recomendaciones para mejorar la selección de materiales. También desarrollaremos recursos para ayudar a los residentes a entender cómo el entorno circundante influye en su salud. Para extender el impacto de este trabajo, crearemos y compartiremos un conjunto de mejores prácticas para que los administradores de propiedades y las organizaciones de inquilinos puedan abogar por utilizar materiales más saludables en las comunidades en las que viven y en las propiedades que administran.

“Nuestra colaboración con HBN es oportuna. Al trabajar junto con los administradores de propiedades, podemos aumentar su conciencia sobre cómo su trabajo impacta nuestra salud y ayudar a cambiar la forma en que seleccionan los materiales”, dijo Vanessa.

En Healthy Building Network, estamos agradecidos por la oportunidad de trabajar con IX y líderes locales como Vanessa a través de la subvención otorgada por MPCA que hace posible esta colaboración. Hacemos un llamado a las agencias públicas, fundaciones e inversionistas privados para que financien iniciativas que busquen desmantelar las inequidades en salud a través de inversión en las comunidades impactadas de manera desproporcionada por la injusticia ambiental, especialmente relacionada con la exposición a sustancias químicas tóxicas. Esperamos pronto poder compartir con ustedes las lecciones, historias y recursos que surgen de esta colaboración.

Have you ever seen a building product advertise that it contains recycled content and wondered what that material actually was and where it came from? We certainly have. Many building products advertise recycled content, but most often the identity and chemical makeup of the recycled material are not shared.

Using products that contain recycled content can be a great way to reduce environmental impacts and support a circular economy by keeping still-useful materials out of landfills and avoiding the impacts of manufacturing virgin materials. Unfortunately, some recycled materials contain toxic chemicals that come along for the ride when incorporated into new products. For example, 2015 testing of a range of vinyl floors found high levels of toxic lead and cadmium from recycled content in the inner layers of the floors.1

Defining recycled content

Recycled content is broadly broken down into pre-consumer and post-consumer materials. As defined by the U.S. Green Building Council2 :

- Post-consumer material is “waste material generated by households or by commercial, industrial, and institutional facilities in their role as end-users of the product, which can no longer be used for its intended purpose.” Some examples of post-consumer recycled material include glass bottles or vehicle tires.

- Pre-consumer material is “material diverted from the waste stream during the manufacturing process.” This definition excludes reuse of scrap materials back into the same process. Some examples of pre-consumer recycled material include treated waste from coal fired power plants (such as fly ash used in carpets or FGD gypsum used in drywall) or waste wood fiber from a sawmill used in composite wood like medium density fiberboard (MDF).

Ensuring safer recycled materials

While some recycled feedstocks, such as sawdust and glass containers, can be safely recycled into new products, others contain legacy contaminants that can lead to toxic exposures when used in new products. To address the potential for toxic re-exposures from recycled materials, HBN worked with green building standards such as LEED and Enterprise Green Communities to include credits that consider not just if a product contains recycled content, but also what that content is and if it has been screened for potential hazards.

Enterprise Green Communities Criterion 6.2, Recycled Content and Ingredient Transparency, acknowledges that the need for content transparency applies to recycled content as well as virgin materials. It calls for using products that contain post-consumer recycled content where the origin of the recycled content is publicly disclosed along with information on how the recycled content is screened for or otherwise avoids heavy metals.

Mind the data gap

Product manufacturers may not always have detailed content information available for the recycled materials they use. Supply chain tracking and internal screening requirements can help manufacturers ensure that the recycled materials they incorporate into new products don’t bring along hazardous contaminants.

Building a Sustainable Future

Removing toxic chemicals from new products makes a commercial afterlife possible, supports a safe and circular economy, and minimizes negative human health impacts. Using materials that are recoverable at the end of their life and building infrastructure to reuse or recycle them will lessen future impacts. Fully and transparently documenting product contents now also supports future recycling by identifying materials that may later be determined to be toxic.

As a building material specifier, the next time you consider a product with recycled content, make sure to ask the manufacturer for full transparency of product content, including where that recycled content came from.

Together we can reduce human exposure and work towards a safe and circular economy.

SOURCES

- Vallette, Jim. “Post-Consumer Polyvinyl Chloride in Building Products.” Healthy Building Network, 2015. https://habitablefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/90-post-consumer-polyvinyl-chloride-pvc-report.pdf.

- USGBC. “Building Product Disclosure and Optimization – Material Ingredients.” U.S. Green Building Council. Accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.usgbc.org/credits/new-construction-core-and-shell-schools-new-construction-retail-new-construction-healthca-24.

Phase 2 of this report is the first of its kind plant-by-plant accounting of the production, use, and releases of chlorine and related pollution around the world. It is intended to inform the efforts of building product manufacturers to reduce pollution in their supply chains.

Chlorine is a key feedstock for a wide range of chemicals and consumer products, and the major ingredient of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic. The report includes details aboutthe production technologies used and markets served by 146 chlor-alkali plants (60 in Asia) and which of these plants supply chlorine to 113 PVC plants (52 in Asia). The report answers fundamental questions like:

- Who is producing chlorine?

- Who is producing PVC?

- Where? How much? And with what technologies?

- What products use the chlorine made in each plant?

Key findings include:

- Over half of the world’s chlorine is consumed in the production of PVC. In China, we estimate that 74 percent of chlorine is used to make PVC.

- 94 percent of plants in Asia covered in this report use PFAS-coated membrane technology to generate chlorine.

- In Asia the PVC industry has traded one form of mercury use for another. While use of mercury cell in chlorine production is declining, the use of mercury catalysts in PVC production via the acetylene route is on the rise. 63 percent of PVC plants in Asia use the acetylene route.

- 100 percent of the PVC supply chain depends upon at least one form of toxic technology. These include mercury cells, diaphragms coated with asbestos, or membranes coated with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), used in chlorine production. In PVC production, especially in China, toxic technologies include the use of mercury catalysts.

Supplemental Documents:

For years, Habitable has been thinking about and consulting with our partners about how to describe the impact of choosing healthier building products. Here’s why this is a complex and challenging issue for the industry:

- Incomplete knowledge of what many building products are made of

- Limited understanding of the health hazards of the thousands of chemicals in commerce today

- Trade-offs when making material choices

These reasons drive the need for full transparency of chemical contents and full assessment of chemical hazards. This can ultimately lead to optimizing products in order to avoid hazardous chemicals.

Toxic chemicals have a huge and complex impact on the health and well-being of people and the environment. Those impacts are spread throughout a product’s life cycle. For example, fenceline communities can be exposed during the manufacturing of products in adjacent facilities, workers can be exposed on the job during the manufacturing and installation processes, and building occupants can be exposed during the product’s use stage. Some individuals suffer multiple exposures because they are affected in all of those instances.

In addition, toxic chemicals can be released when materials are disposed of or recycled. When they incorporate recycled content into new products, manufacturers can include legacy toxicants, inhibiting the circular economy and exposing individuals to hazardous chemicals—even those that have been phased out as intentional content in products.

We know intrinsically that hazardous chemicals have the potential to do harm and that they commonly do so. For champions of this cause, that understanding of the precautionary principle is enough. Others still need to be convinced and often want to quantify the impact of a healthy materials program. How can healthy building champions start to talk about and quantify the impacts of material choices?

Broad Impacts of Toxic Chemicals

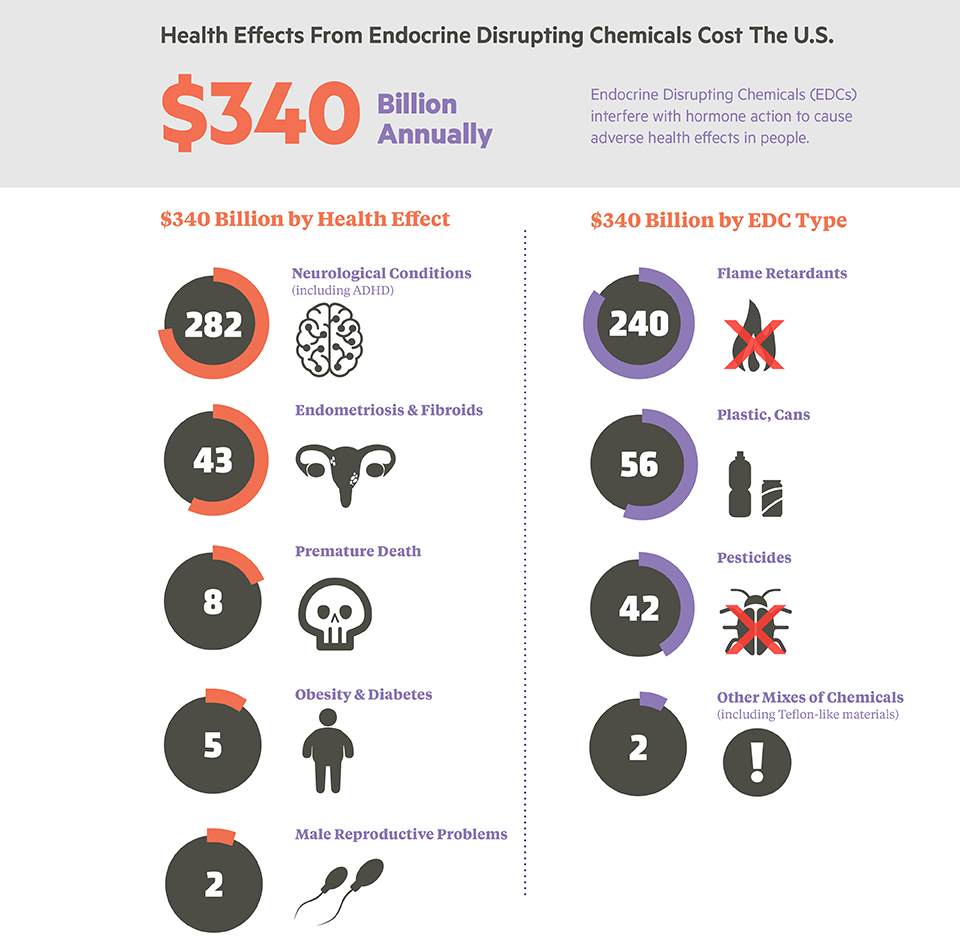

One way researchers quantify the impact of chemicals is to consider the broad economic impacts of chemical exposures. Evidence increasingly shows that toxic chemical exposures may be costing the USA billions of dollars and millions of IQ points. One recent study estimates that certain endocrine-disrupting chemicals cost the United States $340 billion each year. This is a staggerring 2.3% of the US gross domestic product.1 And that is for only a subset of the hazardous chemicals that surround us every day. These numbers provide important context for the larger discussion of toxic chemical use, but cannot easily be tied to daily decisions about specific materials.

Market Scale Impacts

For years, Habitable has been targeting orthophthalates in vinyl flooring as a key chemical and product category combination to be avoided. Orthophthalates can be released from products and deposited in dust which can be inhaled or ingested by residents—particularly young children who crawl on floors and often place their hands in their mouths3. By systematically reducing chemicals of concern in common products, we can all work together to continue to affect this scale of change in the marketplace and keep millions more tons of hazardous chemicals out of buildings.

Impacts on the Project Scale

Context is key for understanding the impact chemical reduction or elimination can have—a pound of one chemical may not have the same level of impact as a pound of another chemical. But, given the right context, this sort of calculation may prove useful as part of a larger story. The following examples provide context for the story of different impacts of different chemicals.

- Small decisions, big impacts: While many manufacturers and retailers have phased out hazardous orthophthalate plasticizers, some vinyl flooring may still contain them. If we consider an example affordable housing project, avoiding orthophthalates in flooring can keep dozens of pounds of these hazardous chemicals out of a single unit (about the equivalent of 10 gallons of milk).4 For a whole building, this equates to several tons of orthophthalates that can be avoided.5 It is easy to see how this impact quickly magnifies in the context of a broader market shift.

- Little things matter: Alkylphenol ethoxylates (APEs) in paints are endocrine-disrupting chemicals make up less than one percent of a typical paint. In this case, by making the choice to avoid APEs, a couple of pounds of these hazardous chemicals are kept out of a single unit (about the equivalent of a quart of milk). This translates to a couple of hundred pounds kept out of an entire building.6 This quantity may seem small compared to the tons avoided in the phthalate example above, but little things matter. Small exposures to chemicals can have big impacts, particularly for developing children.7 And, since our environments can contain many hazardous chemicals, and we aren’t exposed to just a single chemical at a time, these exposures stack up in our bodies.8

- Reducing exposure everywhere: Choosing products without hazardous target chemicals keeps them out of buildings, but can also reduce exposures as these products are manufactured, installed, and disposed of or recycled. Some chemicals may have impacts that occur primarily outside of the residence where they are installed, but these impacts can still be significant. Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), for example, a primary component of vinyl flooring, requires toxic processes for its production and can generate toxic pollution when it is disposed of. Manufacturing of the PVC needed to create the vinyl flooring for one building as described above can release dozens of pounds of hazardous chlorinated emissions, impacting air quality in surrounding communities.9 These fenceline communities are often low-income, and suffer from disproportionate exposure in their homes, through their work, and from local air pollution. If choosing non-vinyl flooring for a single building can help reduce potential exposure to hazardous chlorinated emissions in these fenceline communities, imagine the potential impacts of avoiding vinyl on a larger scale!

In addition to information about target chemicals to avoid, our Informed™ product guidance provides recommendations of alternative types of materials that are typically better from a health hazard perspective and includes steps to work toward the goal of full transparency of product content and full assessment of chemical hazards. This framework can help ensure that toxic chemicals and regrettable substitutions are avoided.

Each decision you make about the materials you use, each step toward using healthier products, can have big impacts within a housing unit, a building, and in the broader environment. Collectively, these individual decisions also influence manufacturers to provide better, more transparent products for us all. Ultimately, this can reduce the hazardous chemicals not just in our buildings but also in our bodies.

SOURCES

- Attina, Teresa M, Russ Hauser, Sheela Sathyanaraya, Patricia A Hunt, Jean-Pierre Bourguignon, John Peterson Myers, Joseph DiGangi, R Thomas Zoeller, and Leonardo Trasande. “Exposure to Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in the USA: A Population-Based Disease Burden and Cost Analysis.” The Lancet 4, no. 12 (December 1, 2016): 996–1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30275-3.

- “Disease Burden & Costs Due to Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals.” NYU Langone Health, July 12, 2019. https://med.nyu.edu/departments-institutes/pediatrics/divisions/environmental-pediatrics/research/policy-initiatives/disease-burden-costs-endocrine-disrupting-chemicals.

- Bi, Chenyang, Juan P. Maestre, LiG Hongwan, GeR Zhang, Raheleh Givehchi, Alireza Mahdavi, Kerry A. Kinney, Jeffery Siegel, Sharon D. Horner, and Ying Xu. “Phthalates and Organophosphates in Settled Dust and HVAC Filter Dust of U.S. Low-Income Homes: Association with Season, Building Characteristics, and Childhood Asthma.” Environment International 121 (December 2018): 916–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.09.013.; Mitro, Susanna D., Robin E. Dodson, Veena Singla, Gary Adamkiewicz, Angelo F. Elmi, Monica K. Tilly, and Ami R. Zota. “Consumer Product Chemicals in Indoor Dust: A Quantitative Meta-Analysis of U.S. Studies.” Environmental Science & Technology 50, no. 19 (October 4, 2016): 10661–72. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b02023.

- According to the USDA, milk typically weighs about 8.6 pounds per gallon. See: “Weights, Measures, and Conversion Factors for Agricultural Commodities and Their Products.” United States Department of Agriculture, June 1992. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/41880/33132_ah697_002.pdf?v=0.

- HBN used the Common Products for Luxury Vinyl Tile and Vinyl Sheet to estimate the amount of plasticizer. We assumed a 100 unit building of 1000 square foot two-bedroom apartments with vinyl flooring throughout the units.

- HBN used the Common Product profiles for Eggshell and Flat Paint to estimate the amount of surfactant and assumed a 100 unit building of 1000 square foot two-bedroom apartments.

- Vandenberg, Laura N., Theo Colborn, Tyrone B. Hayes, Jerrold J. Heindel, David R. Jacobs, Duk-Hee Lee, Toshi Shioda, et al. “Hormones and Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: Low-Dose Effects and Nonmonotonic Dose Responses.” Endocrine Reviews 33, no. 3 (June 1, 2012): 378–455. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2011-1050.

- Impacts can be additive, where health impacts are equal to the sum of the effect of each chemical alone. They can also be synergistic, where the resulting health impacts are greater than the sum of the individual chemicals’ expected impacts.

- HBN used the Common Products for Luxury Vinyl Tile and Vinyl Sheet to estimate the amount of PVC. We assumed a 100 unit building of 1000 square foot two-bedroom apartments with vinyl flooring throughout the units. Emissions are based on the Calvert City, KY Westlake plant examined in HBN’s Chlorine and Building Materials Project. According to EPA’s EJScreen tool, the census blockgroup where this facility is located is primarily low income, with 62% of the population considered low income (putting this census block group in the 88th percentile nationwide in terms of low income population). EJScreen, EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool (Version 2018). Accessed March 18, 2019. https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/.

Two important initiatives are gaining momentum in the green building movement. One seeks to reduce the embodied carbon of building products. The other seeks to increase inclusion, diversity and equity in the green building industry.

It is critical that these efforts align their goals lest, once again, the latest definition and marketing of “green” building products overlooks and overrides the interests of the front line communities most impacted by both climate change and toxic pollution.

The Carbon Leadership Forum describes embodied carbon as “the sum impact of all the greenhouse gas emissions attributed to the materials throughout their life cycle (extracting from the ground, manufacturing, construction, maintenance and end of life/disposal).2 In a widely praised book, The New Carbon Architecture3, Bruce King explains clearly why reducing carbon inputs to building materials immediately—present day carbon releases—is more effective at meeting urgent carbon reduction goals than the gains of even a Net Zero building, which are realized over decades. This approach is embraced by the Materials Carbon Action Network, a growing association of manufacturers and others, which states as its aim “prioritization of embodied carbon in building materials.”(emphasis added).4

Climate action priorities are framed differently by groups at the forefront of movements for climate justice and equity in the green building movement. Mary Robinson, past President of Ireland, UN High Commissioner on Human Rights and UN Special Envoy on Climate Change, says climate justice “insists on a shift from a discourse on greenhouse gases and melting ice caps into a civil rights movement with the people and communities most vulnerable to climate impacts at its heart.” 5 The Equitable and Just National Climate Platform6, adopted by a broad cross section of environmental justice groups and national organizations including Center for American Progress, League of Conservation Voters, Natural Resources Defense Council, and Sierra Club, calls for “prioritizing climate solutions and other policies that also reduce pollution in these legacy communities at the scale needed to significantly improve their public health and quality of life.” The NAACP’s Centering Equity In The Sustainable Building Sector (CESBS)7 initiative advocates “action on shutting down coal plants and other toxic facilities at the local level, as well as building of new toxic facilities, with advocacy to strengthen development, monitoring, and enforcement of regulations at federal, state, and local levels. Also includes a focus on corporate responsibility and accountability.”8

The embodied carbon and climate justice initiatives are aligned when carbon reductions in building products are achieved through industrial process changes that reduce the use of fossil fuels and other petrochemicals. But rarely, if ever, can building products be manufactured with no carbon footprint, i.e. without fossil fuel inputs. These initiatives may not be aligned when manufacturers promote “carbon neutral” or “carbon negative” products that rely on carbon trading or offsets, the practice of supporting carbon reduction elsewhere (by planting trees or investing in renewable energy) to offset fossil fuel and petrochemical inputs at the factory. According to the Equitable and Just National Climate Platform: “ . . . these policies do not guarantee emissions reduction in EJ communities and can even allow increased emissions in communities that are already disproportionately burdened with pollution and substandard infrastructure.” They may also allow increased toxic pollution, if a manufacturer chooses to invest in carbon offsets, for example, rather than invest in process changes that reduce toxic chemical use or emissions. As a result, disproportionate impacts, often correlated with race, can be perpetuated.

Vinyl provides one example of such inequity. Vinyl’s carbon footprint includes carbon tetrachloride, a chemical released during chlorine production that is simultaneously highly toxic, ozone depleting, and a global warming gas 1,400 times more potent than CO2. Offsetting these releases with tree planting or renewable energy purchases does nothing for the toxic fallout, from carbon tetrachloride, fossil fuels and other petrochemicals, on the communities adjacent to those manufacturing facilities.

Experts agree that the most embodied carbon reductions by far are to be had in addressing steel and concrete in buildings. Beyond that, experts disagree about the strength of the data available to track carbon reductions and compare products in a meaningful, objective way, and warn of diminishing returns relative to the investment needed to track carbon in every product. These may prove to be worth pursuing, but not at the expense of meaningful improvements to conditions in fenceline communities.

Habitable believes that these approaches can be reconciled and aligned through dialogue that includes the communities most impacted by the petrochemical infrastructure that is driving climate change. Our chemical hazard database, Pharos, and our collaboration with ChemFORWARD provide manufacturers with the ability to reduce their product’s carbon and toxic footprints.

We can in good faith pursue reductions in embedded carbon and toxic chemical use, climate and environmental justice and to define climate positive building products accordingly. Prioritizing selection of products simply upon claims of carbon neutrality, however, is not yet warranted.

SOURCES

- U.S. Green Building Council, “Resources | U.S. Green Building Council,” LEED, accessed November 14, 2019, http://www.usgbc.org/resources/social-equity-built-environment.

- Carbon Leadership Forum, “Why Embodied Carbon?,” Carbon Leadership Forum (blog), accessed November 14, 2019, http://carbonleadershipforum.org/about/why-embodied-carbon/.]

- Ecological Building Network, “The New Carbon Architecture,” EBNet, accessed November 14, 2019, https://www.ecobuildnetwork.org/projects/new-carbon-architecture.

- Interface, “MaterialsCAN,” accessed November 14, 2019, https://www.interface.com/US/en-US/campaign/transparency/materialsCAN-en_US.

- Martin, “Climate Justice,” United Nations Sustainable Development (blog), May 31, 2019, https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/05/climate-justice/.

- Equitable and Just, “A Just Climate,” accessed November 14, 2019, https://ajustclimate.org.

- NAACP, “NAACP | Centering Equity in the Sustainable Building Sector,” NAACP, accessed November 14, 2019, https://www.naacp.org/climate-justice-resources/centering-equity-sustainable-building-sector/.

- NAACP, “NAACP | NAACP Environmental and Climate Justice Program,” NAACP, accessed November 14, 2019, https://www.naacp.org/environmental-climate-justice-about/.

Discover how bisphenols and phthalates, commonly used in plastics for added strength or flexibility, can disrupt hormone function, and learn ways to reduce their use for improved health in this informative video.

Phase 1 of this report is the first of its kind plant-by-plant accounting of the production, use, and releases of chlorine and related pollution around the world. It is intended to inform the efforts of building product manufacturers to reduce pollution in their supply chains.

Chlorine is a key feedstock for a wide range of chemicals and consumer products, and the major ingredient of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic. The report includes details about the largest 86 chlor-alkali facilities and reveals their connections to 56 PVC resin plants in the Americas, Africa and Europe. (The second phase of this project will inventory the industry in Asia.) A substantial number of these facilities, which are identified in the report, continue to use outmoded and highly polluting mercury or asbestos.

Demand from manufacturers of building and construction products now drives the production of chlorine, the key ingredient of PVC used in pipes, siding, roofing membranes, wall covering, flooring, and carpeting. It is also an essential feedstock for epoxies used in adhesives and flooring topcoats, and for polyurethane used in insulation and flooring.

Key findings include:

- In the United States, the chlor-alkali industry is the only industry that still uses asbestos, importing 480 tons per year on average for 11 chlor-alkali plants in the country (including 7 of the 12 largest plants).

- The only suppliers of asbestos to the chlor-alkali industry are Brazil (which banned its production, although exports continue for the moment) and Russia, whose Uralasbest mine is poised to become the sole source of asbestos once Brazil’s ban is in place.

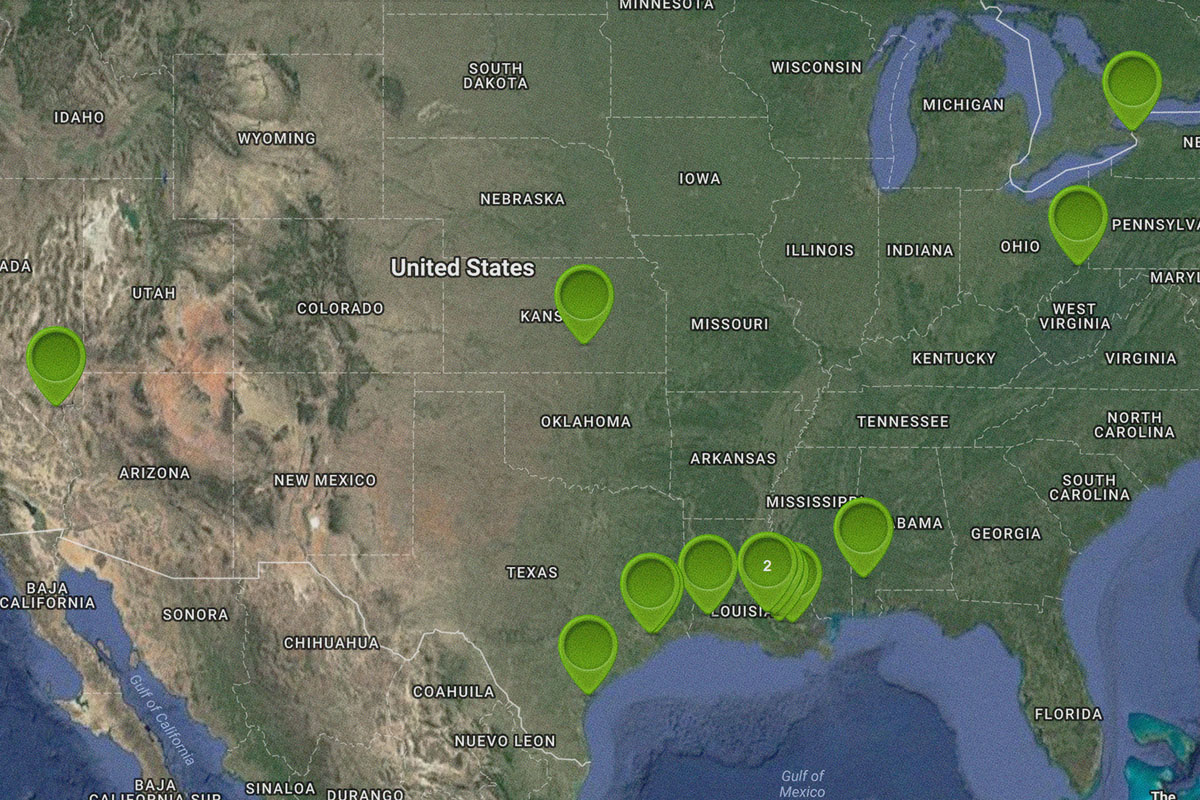

- The US Gulf Coast is the world’s lowest-cost region for production of chlorine and its derivatives. It is home to 9 facilities that use asbestos technology, and some of the industry’s worst polluters including 5 of the 6 largest emitters of dioxin.

- One Gulf Coast facility has been found responsible for chronic releases of PVC plastic pellets into the Gulf of Mexico watershed.

- The US, Russia and Germany are the only countries in this report that allow the indefinite use of both mercury and asbestos in chlorine production.

- The world’s two largest chemical corporations – BASF and DowDuPont – have not announced any plans to phase out the use of mercury and asbestos, respectively, at their plants in Germany.

- Chlor-alkali facilities are major sources of rising levels of carbon tetrachloride, a potent global warming and ozone depleting gas, in the earth’s atmosphere.

- Far more chlorinated pollution, such as dioxins and vinyl chloride monomer, is released from chlor-alkali plants that produce feedstocks for the PVC industry than from plants that produce chlorine for other uses.

Supplemental Documents:

Research from Healthy Building Network (HBN) documents how vinyl building products, also known as PVC or polyvinylchloride plastic, are the number one driver of asbestos use in the US.

The vinyl/asbestos connection stems from the fact that PVC production is the largest single use for industrial chlorine, and chlorine production is the largest single consumer of asbestos in the US. [1] More than 70% of PVC is used in building and construction applications – pipes, flooring, window frames, siding, wall coverings and membrane roofing. [2] This makes the building and construction industry the single largest product sector consuming chlorine, bearing sizeable responsibility for the ongoing demand for asbestos. [3]

Despite the existence of asbestos (and mercury) free chlorine production methods, the PVC industry has positioned itself at the vanguard of industry efforts to frustrate stronger asbestos regulation. According to Mike Belliveau, the Executive Director of the Environmental Health Strategy Center and a senior advisor to Safer Chemicals Healthy Families coalition, “The PVC market has spurred chemical industry lobbyists to urge the Trump Administration to exempt their use of deadly asbestos from future restrictions.” The last time the vinyl industry positioned themselves so publicly on the other side of common sense, they were defending the use of lead in children’s vinyl lunch boxes.

Among HBN’s Findings:

- The U.S. chlor-alkali industry (Olin/Dow, Occidental, and Westlake/Axiall [4]) consumed 88% of asbestos imports in 2014, and all asbestos imports in 2016.

- Three U.S. chemical companies are importing 1.2 million pounds of asbestos per year for use in 15 chlor-alkali plants. PVC used in building products requires an estimated 250,000 pounds of imported asbestos per year.

- Asbestos miners in Minaçu, Brazil, are literally dying to prop up the U.S. chemical and PVC building product industries’ reliance on asbestos. Dozens of asbestos baggers are dying or have died of asbestos related diseases, according to local reports. [5] Overall, Brazil exports over 13,000 bags of asbestos each year to the U.S. chlorine industry.

- Occidental Chemical imported 900,000 pounds of asbestos from Oct. 2013 through 2015, but apparently failed to report those imports to the EPA in possible violation of the Chemical Data Reporting rule as required under TSCA.

- Asbestos imports by Occidental Chemical and Olin Corporation more than doubled from 2015 to 2016, perhaps indicating a stockpiling of asbestos in anticipation of further restrictions on mining in Brazil or use in the U.S.

- Russia shipped asbestos to Dow in 2014 and to Olin in 2016 (when Olin took over Dow’s U.S. chlor-alkali plants). If the mine in Brazil closes, the U.S. chlor-alkali industry’s backup plan is the massive mine in Asbest, Russia.

The health hazards of asbestos exposure, painful and deadly lung diseases including cancer, are clear. Green building professionals do not have to wait. Do your part to prevent asbestos-related diseases here and abroad. Don’t specify vinyl building products.

SOURCES

1. In the US more than half of chlorine is produced using asbestos, despite the availability of an alternative production method that does not require either asbestos or mercury.

2. http://www.vinylinfo.org/vinyl/uses

3. According to IHS Markit, “A majority of chlor-alkali capacity is built to supply feedstock for ethylene dichloride (EDC) production. EDC is then used to make vinyl chloride (VCM) and subsequently used to manufacture polyvinyl chloride (PVC). This chain, EDC to VCM to PVC, is normally called the vinyl chain. PVC demand correlates closely with construction spending, therefore, it can be concluded that chlorine consumption and production are driven by the construction industry. Hence, chlorine consumption growth depends on the growth of the global economy, since a country will spend more on construction if it has a healthy gross domestic product.” (IHS Markit. “Chemical Economics Handbook: Chlorine/Sodium Hydroxide (Chlor-Alkali),” December 2014. https://www.ihs.com/products/chlorine-sodium-chemical-economics-handbook.html)

4. Fifteen chlor-alkali plants last reported to be using asbestos diaphragms include, in order of estimated chlorine capacity:

-

- Olin (formerly Dow), Freeport, Tex. (3,158,000 tons per year)

- Westlake (formerly Axiall), Lake Charles, La. (1,100,000 tpy)

- Olin, Plaquemine, La. (1,068,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Ingleside/Corpus Christi, Tex. (668,000 tpy)

- Occidental, La Porte, Tex. (580,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Hahnville/Taft, La. (567,000 tpy)

- Olin, McIntosh, Ala. (468,000 tpy)

- Westlake, Plaquemine, La. (410,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Convent, La. (389,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Niagara Falls, N.Y. (336,000 tpy)

- Westlake, Natrium/New Martinsville, W.Va. (297,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Geismar, La. (273,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Wichita, Kans. (182,000 tpy)

- Occidental, Deer Park, Tex. (162,500 tpy)

- Olin, Henderson, Nev. (153,000 tpy)

5. Carpentier, Steve. “Minaçu, a cidade que respira o amianto.” CartaCapital, May 21, 2013. http://www.cartacapital.com.br/sustentabilidade/minacu-a-cidade-que-respira-o-amianto-8717.html

This paper was prepared by Perkins+Will, in partnership with Healthy Building Network (HBN), as part of a larger effort to promote health in the built environment. Indoor environments commonly have higher levels of pollutants, and architects and designers may frequently have the opportunity to help reduce or mitigate exposures.

The purpose of this report is to present information on the environmental and health hazards of PVC, with an emphasis on information found in government sources. This report is not intended to be a comprehensive analysis of all aspects of the PVC lifecycle, or a comprehensive comparative analysis of polymer lifecycles. Rather, in light of recent claims that PVC formulas have been improved by reducing certain toxic additives, this paper reviews contemporary research and data to determine if hazards are still associated with the lifecycle of PVC. This research has been surveyed from a perspective consistent with the precautionary principle, which, as applied, means that where there is some evidence of environmental or human health impact of PVC that reasonable alternatives should be used where possible. Furthermore, and more generally, this paper is intended to build greater awareness of this common building material.

Home Depot, the world’s largest purchaser of building products, announced that by the end of 2015 it will eliminate phthalate plasticizers from the vinyl flooring it sells.

Phthalates are endocrine disrupting chemicals that have been banned in children’s products since 2008 but are still widely used in a wide range of vinyl products to make them flexible.

The announcement came after lengthy negotiations led by the Mind The Store Campaign, a grassroots effort supported by the Healthy Building Network’s (HBN) cutting-edge research on building products. Mind The Store is challenging the country’s largest retailers to restrict 100 hazardous chemicals in the products they sell. Also today, the Mind The Store campaign released a report identifying phthalates and other chemical hazards detected in vinyl flooring products.

HBN first addressed the issue of phthalate substitution in polyvinyl chloride (PVC or “vinyl”) flooring in our 2014 report, Phthalate-free Plasticizers in PVC. The HBN analysis was intended to help purchasers evaluate the claims of phthalate-free product lines in order to make informed choices about a wide array of materials including flooring, wall guards and coverings, wire and cabling, upholstery and membrane roofing. And it worked: the report helped to convince Home Depot that change was possible in short order. Now that Home Depot has acted, the whole industry will surely follow.

And what a relief it will be for people who live, work and play on vinyl floors. PVC sheet floors can contain over 20% phthalate plasticizers. These semi-volatile organic compounds readily migrate from flooring into dust and are inhaled by building occupants. Researchers are finding that exposures to phthalates occurs in the womb as well as after birth, and can impair the development of lungs and immune systems. This disruption in turn can lead to the development of asthma, as we first reported in 2004, and genital deformities in boys.

For over a decade now, leading green designers, architects and building owners have taken a precautionary approach, avoiding PVC building products in commercial buildings as evidence grew of the many toxic impacts associated with PVC and its additives. As a result, phthalate-free formulations of vinyl floor and wall coverings began appearing in this market a few years ago. Home Depot’s leadership marks a tipping point that will bring these products to everyone.

Equity

Equity Pollution

Pollution Health

Health Climate Change

Climate Change