READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORTPlastic is a ubiquitous part of our everyday lives, and its global production is expected to more than triple between now and 2050. According to industry projections, we will create more plastics in the next 25 years than have been produced in the history of the world so far.

The building and construction industry is the second largest use sector for plastics after packaging.1 From water infrastructure to roofing membranes, carpet tiles to resilient flooring, and insulation to interior paints, plastics are ubiquitous in the built environment.

These plastic materials are made from oil and gas. And, due to energy efficiency improvements, for example–in building operations and transportation–the production and use of plastics is predicted to soon be the largest driver of world oil demand.2

Plastic building products are often marketed in ways that give the illusion of progress toward an ill-defined future state of plastics sustainability. For the past 20 years, much of that marketing has focused on recycling. But for a variety of reasons, these programs have failed.

A recent study from the University of Michigan makes it clear that the scale of post-consumer plastics recycling in the US is dismal.3 Only about 8% of plastic is recycled, and virtually all of that is beverage containers. Further, most of the recyclate is downcycled into products of lower quality and value that themselves are not recyclable. For plastic building materials, the numbers are more dismal still. For example, carpet, which claims to have one of the more advanced recycling programs, is recycled at only a 5% rate, and only 0.45% of discarded carpet is recycled into new carpet. The rest is downcycled into other materials, which means their next go-around these materials are destined to be landfilled or burned.4 After 20 years of recycling hype, post-consumer recycling of plastic building materials into products of greater or equal value is essentially non-existent, and therefore incompatible with a circular economy.

Why isn’t plastic from building materials recycled?

Additives (which may be toxic), fillers, adhesives used in installation, and products made with multiple layers of different types of materials all make recycling of plastic building materials technically difficult. Lack of infrastructure to collect, sort, and recycle these materials contributes to the challenge of recycling building materials into high-value, safe new materials.

Manufacturers have continued to invest in products that are technically challenging to reuse or recycle – initially cheaper due to existing infrastructure – instead of innovating in new, circular-focused solutions. Additionally, their investment in plastics recycling has been paltry. In 2019 BASF, Dow, ExxonMobill, Shell and numerous other manufacturers formed the Alliance to End Plastic Waste (AEPW) and pledged to invest $1.5 billion over the next five years into research and development of plastic waste management technologies. Compare that to the over $180 billion invested by these same firms in new plastic manufacturing facilities since 2010.5

Globally, regulations that discourage or ban landfilling of plastics have, unfortunately, not led to more recycling overall. Instead, burning takes the place of landfilling as the eventual end of life for most plastics.

Confusing rhetoric around plastic end of life options can make this story seem more complicated than it is.6

- “incineration” or “waste to energy” burns plastic for energy.

- “Plastic-to-fuel” or “gasification” or “pyrolysis” generates fuel. This output is rarely used for anything but burning due to the additional processing required to use for any other purpose.

- “Chemical recycling” could, in theory, lead to new plastic products. This technology is unproven and currently not a scalable solution. The outputs are often burned due to low quality.

Plastic waste burning, regardless of the euphemism employed, is a well established environmental health and justice concern.

Burning plastics creates global pollution and has environmental justice impacts.

In its exhaustive 2019 report, the independent, nonprofit Center for International Environmental Law (CEIL) documents how burning plastic wastes increases unhealthy toxic exposures at every stage of the process. Increased truck traffic elevates air pollution, as do the emissions from the burner itself. Burned plastic produces toxic ash and residue at approximately one fifth the volume of the original waste, creating new disposal challenges and new vectors of exposure to additional communities that receive these wastes.7

In the US, eight out of every 10 solid waste incinerators are located in low-income neighborhoods and/or communities of color.8 This means, in some cases, the same communities that are disproportionately burdened with the pollution and toxic chemical releases related to the manufacture of virgin plastics are again burdened with its carbon and chemical releases when it is inevitably burned at the end of its life.

The issue is global in scale. A recent report by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) found that “plastic waste incineration has resulted in disproportionately dangerous impacts in Global South countries and communities.” The Global Alliance for Incineration Alternatives (GAIA), a worldwide alliance of more than 800 groups in over 90 countries, has been working for more than 20 years to defeat efforts to massively expand incineration, especially in the Global South. GAIA members have identified incineration not only as an immediate and significant health threat in their communities, but also a major obstacle to resource conservation, sustainable economic development, and environmental justice.

Where do we go from here?

- Minimize production of virgin plastic. This should be the main focus of any plastic waste reduction plan and part of any comprehensive climate change initiative. Policies banning single use plastics or banning the construction of new plastic production facilities or facility expansions are two example solutions cited by GAIA.9 Less plastic means less waste and less material to incinerate.

- Invest in true circular economy initiatives. These may include, for example: extended producer responsibility programs, materials passports, materials disclosure, elimination of toxic chemical additives, product as a service models, and recycling facilities that support upcycling. By shifting industry investments toward circular economy infrastructure – instead of the nearly $200 billion investments in increased manufacturing and burning capacity – the plastic industry could start to be part of the solution of reducing plastic waste.

- When evaluating the “expense” of recycling and circularity vs business-as-usual, a fair calculation for the latter needs to include all costs associated with the production, use, and end of life impacts of plastics. That “cheap” vinyl floor is no longer so inexpensive when the full costs of global pollution and the health burdens of people of color and low income communities are included in the math. Externalities must be a part of the equation.

What is unquestionable is this: Today our only choices for plastic waste are to burn or landfill most of it. Expanding plastics production and incineration is a conscious decision to perpetuate well documented, fully understood inequity and injustice in our building products supply chain.

The folks at The Story of Stuff cover this in The Story of Plastics, four minute animated short suitable for the whole family. Comedian John Oliver tells the “R-rated” version of the story with impeccable research and insightful humor in his HBO show Last Week Tonight. It’s worth a look to learn exactly how the plastics industry uses the illusion of recycling to sell ever increasing volumes of plastic. Without manufacturer responsibility and investment, efforts to truly incorporate plastic into a circular economy have little chance of success.

SOURCES

- https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution

- https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/bee4ef3a-8876-4566-98cf-7a130c013805/The_Future_of_Petrochemicals.pdf See page 18, 30.

https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/us-energy-facts/ - https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab9e1e/pdf

- https://carpetrecovery.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CARE-2019-Annual-Report-6-7-20-FINAL-002.pdf

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jan/21/founders-of-plastic-waste-alliance-investing-billions-in-new-plants

- https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/False-solutions_Nov-9-2020.pdf

- https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Plastic-and-Climate-FINAL-2019.pdf

- https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d14dab43967cc000179f3d2/t/5d5c4bea0d59ad00012d220e/1566329840732/CR_GaiaReportFinal_05.21.pdf

- https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/False-solutions_Nov-9-2020.pdf

When celebrated Victorian painter Edward Burne-Jones learned that a favorite pigment—it was called Mummy Brown—was in fact manufactured from the desecrated Egyptian dead, he banished it from his palette and bore his remaining tubes to a solemn burial in his English garden.[1] Once you know better, you have to do better.

Transparency in the supply chain can reveal inconvenient truths about favored products. A fascinating new article about the plywood supply chain brings into view new incentives to stop using fly ash in building products.

In What You Don’t See, Brent Sturlaugson, a practicing architect and associate professor at the University of Kentucky attempts a full accounting of the environmental, social, financial, and political impacts he attributes to the supply chain for Georgia Pacific (GP) plywood. He opens his ledger at the world’s largest open pit coal mine, Peabody Energy’s North Antelope Rochelle Mine, located in the heart of Wyoming’s Thunder Basin National Grasslands. From there the environmental and health costs add up, many of them allocated to the utility that powers GP’s Madison, Georgia plant. The Robert W. Scherer Plant in Monroe County, Georgia, has been calculated to be the largest, dirtiest coal fired power plant in the United States.[2]

This caught the attention of the Healthy Building Network (HBN) Research Team, who previously identified this power plant as a huge mercury polluter. It is also the leading supplier of fly ash to U.S. carpet companies that use the ash as filler—replacing limestone in carpet tiles—in order to qualify for recycled content credits in LEED, the Living Building Challenge, and various government procurement standards. What we had not realized was that the Scherer plant relied upon a single source of coal, the North Antelope Rochelle Mine. HBN and others[3] have long recommended against the use of fly ash in various building products because of the heavy metal content of the ash and the cost incentives fly ash “recycling” provide to continue burning coal – absent reuse, the fly ash must be expensively managed as a hazardous waste. What You Don’t See compels us to consider the ash as processed coal, the original raw material ingredient. In this case, coal mined from the seam of a single, particularly gnarly open pit mine.

Located near Gillette, WY, the mine occupies territory whose history is steeped in the genocide of Indigenous Peoples who negotiated treaty rights to the region in the mid-1800’s. By the end of the century they lost their livelihood to the extermination of the American Bison, and then their land to well-documented, systemic treaty violations. Environmentalists and ranchers alike view the mine as a disaster for the local and global environment. It is a financial disaster for the American taxpayer, according to the U.S. General Accounting Office which cites the mine as an example of corrupt Bureau of Land Management practices that include no bid contracts, financial terms that deprive the U.S. of fair market value, and a brazen lack of transparency. All in violation of federal laws and regulations.

Squandered water and subsidized carbon emissions are only the beginning of the staggering sustainability losses from this coal, according to Sturlaugson’s detailed accounting, which also includes: “dark money” political contributions from the Koch brothers, the use of bankruptcy laws to renege on union pension obligations, and significant releases of toxic chemicals that can cause cancer, respiratory disease, and reproductive and neurological impacts.

Like the rich umber of Mummy Brown pigment, recycled coal ash in building products has a superficial appeal, until you learn the truth. What You Don’t See opens our eyes even wider to the reasons why the use of coal ash—processed coal—is unacceptable in green buildings and building products. Burying these products in our gardens or landfills won’t do. But we can and must root them out of our green rating system and recycling incentives.

SOURCES

- From the article Blue As Can Be, by Simon Schama, a fascinating history of prized (frequently toxic) artistic pigments. Schama, Simon. “Blue as Can Be.” The New Yorker, September 3, 2018.

- Schneider, Jordan, Travis Madsen, and Julian Boggs. “America’s Dirtiest Power Plants: Their Oversized Contribution to Global Warming and What We Can Do About It.” Environment America Research & Policy Center, September 2013. https://environmentamericacenter.org/sites/environment/files/reports/Dirty%20Power%20Plants.pdf.

- BuildingGreen and Perkins+Will are among those that have recommended against the use of coal fly ash in certain building products. Wilson, Alex. “OP-ED: EBN’s Position on Fly Ash.” Environmental Building News, August 30, 2010. https://www.buildinggreen.com/op-ed/ebns-position-fly-ash.; Glazer, Breeze, Craig Graber, Carolyn Roose, Peter Syrett, and Chris Youssef. “Fly Ash in Concrete.” Perkins+Will, November 2011. http://assets.ctfassets.net/t0qcl9kymnlu/1Tx57nRsWYYMEC824CkOaI/38239c5e0fb2044af10bc2b1fac38cf8/FlyAsh_WhitePaper.pdf.

- Vallette, Jim, Rebecca Stamm, and Tom Lent. “Eliminating Toxics in Carpet: Lessons for the Future of Recycling.” Healthy Building Network, October 2017. https://habitablefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/81-eliminating-toxics-in-carpet-lessons-for-the-future-of-recycling.pdf. (see p. 21)

- Walsh, Bill. “Home Depot Raises The Bar On Hazard Avoidance – New Chemical Strategy Is An Important Step Towards Healthier Product Options.” Healthy Building Network Blog, October 25, 2017. https://habitablefuture.org/resources/home-depot-raises-the-bar-on-hazard-avoidance/.

Healthy Building Network’s report on post-consumer carpet feedstocks calls for eliminating over 40 highly toxic chemicals in carpets that threaten public health and impede recycling. These toxics are known to cause respiratory disease, heart attacks, cancer, and asthma, and impair children’s developmental health.

The report outlines strategies to protect public health and the environment by improving product transparency, eliminating dangerous chemicals from carpets, and increasing carpet recycling rates. It also reveals surprising efforts in the industry to remove many of these toxic substances from carpet design.

Asphalt (also known as asphalt concrete, bitumen, or road tar) is the most common paving material by far, accounting for a 92 percent share of the 2.5 million miles of roads and highways in the United States. Reclaiming and reusing asphalt has many benefits, including waste prevention, reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, and lower lifecycle impacts compared to virgin asphalt material use.

Keys to increasing the recycling of asphalt and its attendant environmental benefits include simplifying the designs of asphalt mixes, reducing toxic additives in production, tracking materials from production through use and recycling, testing incoming materials for contaminants, and avoiding the addition of cutback solvents and other toxic rejuvenating agents.

Healthy Building Network’s research into current recycling practices for flexible polyurethane foam (FPF) indicates that most post-consumer feedstocks are contaminated with highly toxic flame retardants.

Discussions of recycling FPF have centered around the human health and environmental hazards posed by the flame retardant PentaBDE, which the foam industry phased out a decade ago. But the flame retardants that have replaced PentaBDE present similar concerns. Manufacturers incorporate flame retardant-laden post-consumer FPF into new products, primarily bonded carpet cushion. Recycling and installation workers and building occupants, particularly crawling children, can be exposed to these toxic chemicals. The recent emergence of pre-consumer FPF scrap that is free of flame retardants is a great step toward a safer, more valuable feedstock, but more work is needed to track and label flame retardant-free FPF to ensure that future post-consumer foam is also flame retardant-free.

Polyethylene is the world’s most common plastic. It is used in packaging, food and beverage containers, and consumer products.

Building product manufacturers sometimes use post-consumer recycled polyethylene bags and bottles in pipes and plastic lumber. This scrap usually has minimal contents of concern, but products like detergents stored in plastic packaging can remain. So-called “bio-degradation” agents in plastic bags also contaminate this feedstock and should never be used. The plastics recycling industry is developing protocols to screen out residual contaminants. Of greatest concern: Most polyethylene goes unrecycled in the United States due to problems in supply chain controls and the low price of virgin resins. This report examines ways to optimize the use of post-consumer polyethylene in building materials.

Not all recycled content materials are created equal – especially when it comes to recycled plastics.

In a report released by StopWaste and the Healthy Building Network, we take an in-depth look at the health implications, supply chain considerations, and potential to scale up recycling of the world’s most common plastic: polyethylene (aka PE). [1] This report, Post-Consumer Polyethylene in Building Products, is the latest installment in our Optimizing Recycling series.

Polyethylene is a material widely used in product packaging, beverage containers, and myriad consumer products. High Density Polyethylene (HDPE), Low Density Polyethylene (LDPE), and Linear Low Density Polyethylene (LLDPE) are all readily recyclable in California. Polyethylene plastic scrap bottles and plastic bags usually have minimal contents of concern and are easily processed into feedstock for new products, including building materials. Despite the great potential for recovery of PE, sizeable barriers stand in the way of a lot more recycling.

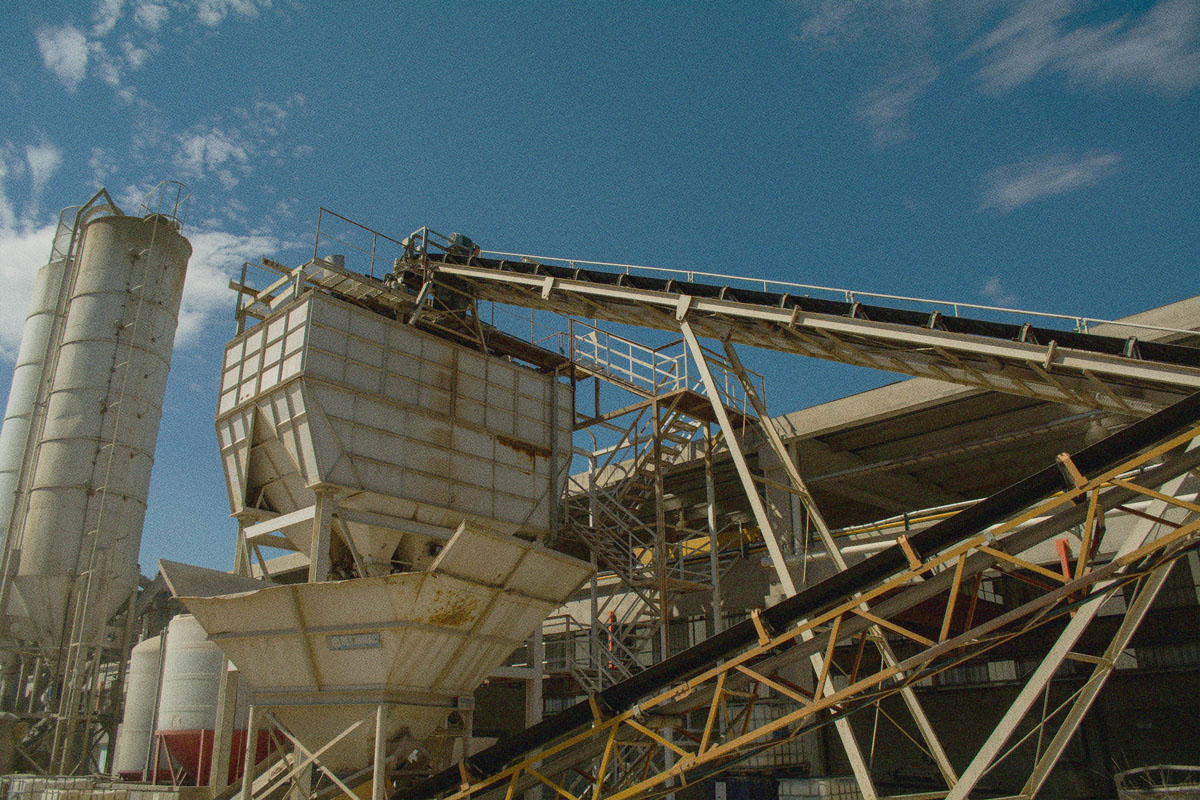

The explosive growth in virgin ethylene production on the U.S. Gulf Coast, driven by cheap energy, has meant that most post-consumer scrap PE is either landfilled, incinerated, or sent overseas for processing. [2]

Industry trends in recycling collection technology are also undermining the value of post-consumer polyethylene feedstocks. Pipe and plastic lumber manufacturers in the U.S. require supplies that have minimal amounts of contaminants such as volatile residual substances in packaging and other types of plastics. Yet proportionally less “good material” is coming out of the plastic waste recycling stream due to the rising use of municipal single stream recycling over the past decade. Mixed and low quality scrap materials that come from single-stream recycling centers are more likely to be exported than sorted and screened for high-quality polyethylene scrap. As a result, more recovered plastic bags are exported than processed domestically. [3]

Additives used for plastics can turn into contaminants when recycled. As seen with other recycled content materials, feedstocks with less contamination have an increased potential for recyclability as well as increased value to purchasers. [4] For PE, contaminants come in the form of residual materials from packaging (residue from bottles that contained pesticides, for example), or from additives used in manufacturing to achieve certain product characteristics. Perhaps the most problematic additive to PE products are so-called biodegradation additives used in plastic packaging. These additives (but not the rest of the plastic) degrade when exposed to sunlight or other environmental conditions. When these products are collected and used as post-consumer recycled feedstocks in products like pipes and decking, however, these additives can lower the reliability and value of a manufacturer’s product. This is why, in our report, we recommend that plastic manufacturers stop using degradability additives in all new polyethylene.

SOURCES

- Polyethylene sales accounted for 35% of all USA plastic resin sales in 2014. The next most common resins, polypropylene and polyvinyl chloride, accounted for 15 percent and 14 percent, respectively. (American Chemistry Council. “2015 Resin Review,” April 2015.)

- In 2005, the Healthy Building Network and the Institute for Local Self-Reliance examined the market for lumber made from recycled plastic. The report rated fourteen plastic lumber products as “most environmentally preferable” because they contained only polyethylene plastics and, according to the manufacturer at the time, at least 50% of the polyethylene was from post-consumer sources. (Platt, Brenda, Tom Lent, and Bill Walsh. “The Healthy Building Network’s Guide to Plastic Lumber.” Institute for Local Self-Reliance, June 2005. https://www.greenbiz.com/sites/default/files/document/CustomO16C45F64528.pdf.) At least eight of these fourteen products remain on the market, but current literature reveals that most if not all have decreased post-consumer content in favor of pre-consumer (factory-generated) scrap or even virgin polyethylene. Plastic lumber products listed in the report that are still on the market include: SelectForce; PlasTEAK; TRIMAX; American Plastic Lumber’s HPDE decking; Perma-Deck Advantage+; Eco-Tech; Enviro-Curb; and MAXiTUF. Resco Plastics, manufacturer of MAXiTUF plastic lumber, explains, “Due to the current price increases for our raw material, Resco Plastics, Inc. is no longer able to guarantee its post consumer content.” (Resco Plastics Incorporated. “Plastic Lumber Warranty,” 2016. http://rescoplastics.com/warranty/.)

- Plastic scrap exports to Asia have soared since 2000. This trend continued through 2013, the most recent year for which data are available from the Society of the Plastics Industry. Of the plastic film collected for recycling in the US, only 42 percent was processed in the U.S. or Canada. Shippers exported the remaining 58 percent. (Taylor, Michael D. “The State of Plastics Recycling in the U.S.” presented at the 11th China International Forum on Development of the Plastics Industry & China Plastics Recycling/ Reutilization Forum, Yuyao, China, October 2015. http://www.slideshare.net/mdairtaylor/the-state-of-plastics-recycling-in-the-us.)

- See our report Optimizing Recycling: Criteria for Comparing and Improving Recycled Feedstocks in Building Products for more on how additives and contaminants can affect common post-consumer recycled feedstock materials markets.

The recycling industry has made significant strides toward a closed loop material system in which the materials that make up new products today will become the raw material used to manufacture products in the future. However, contamination in some sources of recycled content raw material (“feedstock”) contain potentially toxic substances that can devalue feedstocks, impede growth of recycling markets, and harm human and environmental health.

Since May 2014, the Healthy Building Network, in collaboration with StopWaste and the San Francisco Department of Environment, has been evaluating 11 common post-consumer recycled-content feedstocks used in the manufacturing of building products. This paper is a distillation of that larger effort, and provides analysis on two major feedstocks found in building products: recycled PVC and glass cullet. This research partnership seeks to provide manufacturers, purchasers, government agencies, and the recycling industry with recommendations for optimizing the use of recycled content feedstocks in building products in order to increase their value, marketability and safety. This report was prepared in support of a research session at the 2015 Greenbuild conference in Washington, DC.

New HBN research reveals that legacy toxic hazards are being reintroduced into our homes, schools and offices in recycled vinyl content that is routinely added to floors and other building products. Legacy substances used in PVC products, like lead, cadmium, and phthalates, are turning up in new products through the use of cheap recycled content.

Funding for research on post-consumer PVC feedstock was provided by StopWaste and donors to the Healthy Building Network (HBN). It was conducted using an evaluative framework to optimize recycling developed by StopWaste, the San Francisco Department of the Environment, and HBN. This briefing paper on post-consumer recycled PVC is a prequel to a forthcoming white paper by this new collaboration.

Source separation of waste streams and toxic content restrictions are crucial actions toward optimizing the value of recycled feedstocks in building products. HBN’s research on glass waste – known as cullet – reveals the multitude of economic and environmental benefits of these practices.

The ability of fiber glass insulation manufacturers to incorporate cullet increases; the wasteful landfilling of discarded glass (nationally, only 28% is recycled) decreases. Manufacturers need less energy to produce insulation, leading to lower greenhouse gas emissions. Workers, surrounding neighborhoods, and the environment at large are exposed to fewer toxic contaminants. Post-Consumer Cullet in California is the second in a series of Healthy Building Network reports for the Optimizing Recycling collaboration.

Equity

Equity Health

Health Climate Change

Climate Change Pollution

Pollution