READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORT

READ HABITABLE’S NEW REPORTWatch Habitable’s webinar featuring findings from our report Designing Out Plastics: A Blueprint for Healthier Building Materials and hear why leaders like sidexside and CannonDesign are choosing to design out plastics and design in health.

Featuring

Also Featuring

Habitable, Principal Researcher

Habitable, VP Market Transformation

Download the Report

This special report from Habitable and Plastic Pollution Coalition reveals how the built environment is full of toxic plastic, making wildfires worse—and how there is opportunity to build back better, with sustainable materials.

The report presents key findings about the links between plastics and wildfires, focusing on the case study of the January 2025 wildfires that burned through Los Angeles, California—an example of our increasingly plastic cities. It seeks to inform leaders in architecture, building, design, engineering, and policy spaces about how communities at risk of and/or affected by wildfires can build and rebuild better with safer, plastic-free materials.

A growing number of building professionals, policymakers, real estate developers, and philanthropic funders have awoken to the shocking volume of plastic building materials in use today and the devastating harm they cause to human and environmental health. Find out why these leaders now see healthier alternatives to plastic building materials as the next frontier in the building and construction sector.

Key Takeaway #1

Plastics harm human and environmental health at every stage of their life cycle, from extraction through production and disposal.

Almost all plastics are made from fossil fuels, while the chemicals used to produce them are linked to cancer, reproductive harm, developmental issues, and other health harms. They also release microplastics which contaminate our environment and our bodies, and at the end of their life, plastics create massive amounts of waste. Tragically, these impacts fall hardest on children and on low-wealth, Indigenous, and communities of color.

Key Takeaway #2

The building sector is a leading driver of plastics use and continues to grow.

From flooring and siding to insulation and even paint, the building and construction sector accounts for 17% of global plastic production – second only to packaging. Plastic use in construction is on track to nearly double by 2050, intensifying its environmental and health harms. In fact, driven in large part by building materials, the plastics industry is expected to produce more plastic in the next 25 years than in all of history to date.

Key Takeaway #3

The building sector’s heavy reliance on plastics creates a unique and severe danger to human and environmental health.

The sector uses 70% of all PVC (vinyl) produced globally and 30% of all polystyrene—two of the most hazardous plastics. Plastic building materials make buildings less fire resistant, burning faster and hotter while generating more toxic chemicals than natural materials—posing an escalating threat as climate change fuels more severe wildfires.

Key Takeaway #4

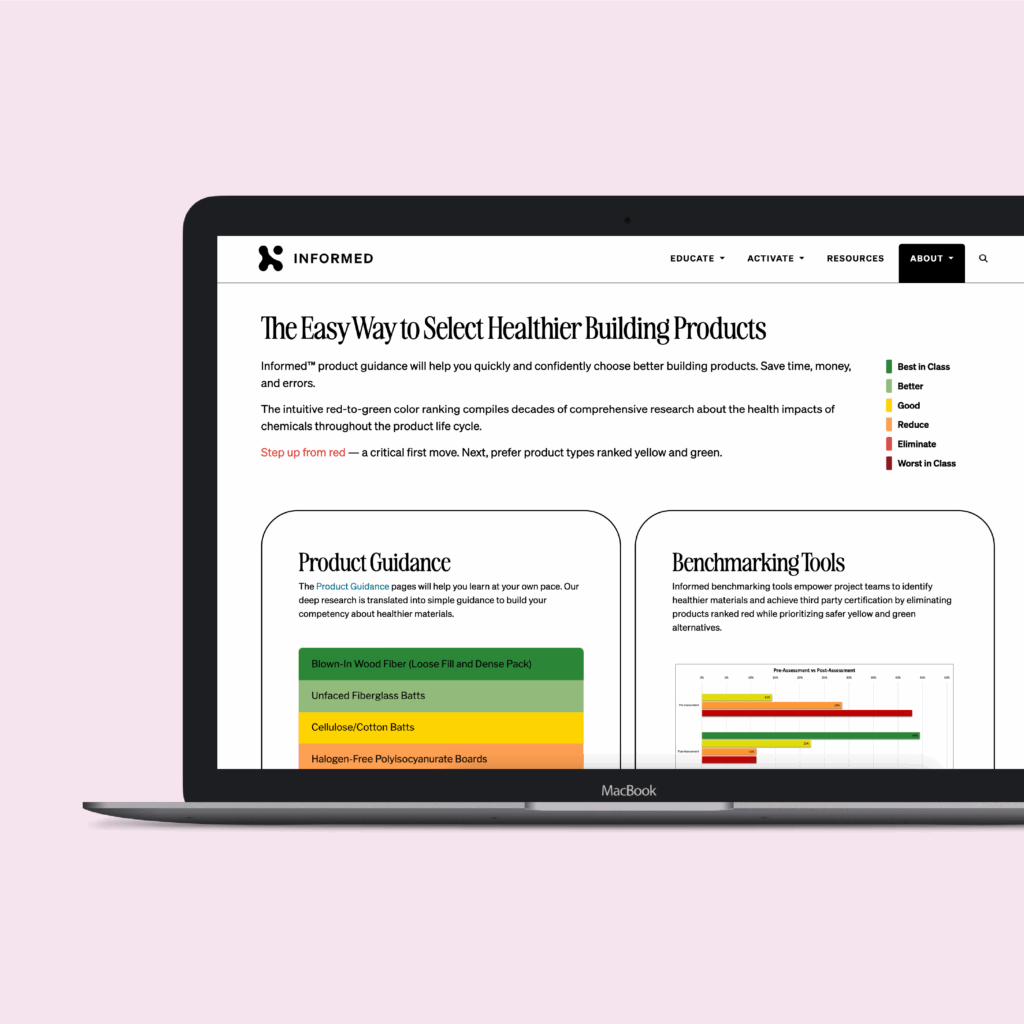

Healthier alternatives are already available and can significantly reduce our reliance on plastic building materials.

Habitable has identified healthier, no/low-plastic alternatives for many plastic building products. Informed™ product guidance can help developers, designers, builders, homeowners, and policymakers find healthier alternatives to plastics.

Recommendations

Download the Report

Download the full report for more information including examples of solutions from leaders like CannonDesign and Sera Architects.

Take a moment and look around. Try to find something—anything—that isn’t made with plastic. Your coffee cup lid, the synthetic fabric of your shirt, the carpet under your feet, the paint on the walls, the foam in your chair, even the “rubber” gaskets in your windows—they’re all plastic. Terms like polyester, nylon, vinyl, latex, acrylic, and spandex are just different names for the synthetic polymers we know as plastic.

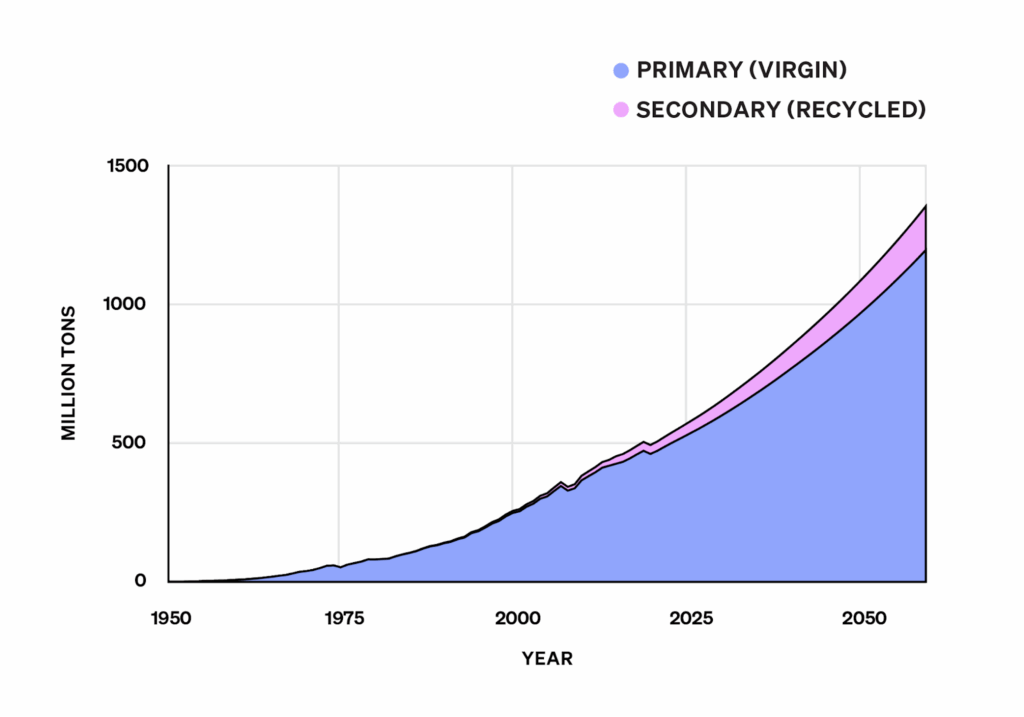

Over the past 75 years, plastics have infiltrated daily life largely without question. Production skyrocketed from an estimated 2 million tons in 1950 to more than 470 million tons in 2019.1 And without intervention, plastic use is projected to surge in the decades to come.

Plastic’s ubiquity isn’t accidental. It has revolutionized modern life through life-saving medical devices, lightweight materials that improve fuel efficiency, and countless innovations. Despite their benefits, plastics are also one of our most pressing environmental and health challenges. They are made from fossil fuels and contribute to climate change. The chemicals used to make plastics have been linked to cancer, reproductive dysfunction, and other health harms. They pollute the air, water, soil, and our bodies, and create massive amounts of waste at the end of their—often too short—useful lives.

The good news? Change is happening. Across sectors and industries, sustainability professionals are reducing plastic use, municipalities are implementing plastic reduction policies, and innovative alternatives are reaching the market. We have unprecedented opportunities to drive meaningful change in reducing plastics’ impacts. Here we’ll provide facts you need to understand plastics’ impact and pathways forward.

- What are plastics?

- How are plastic products made?

- How do plastics drive fossil fuel demand?

- How much plastic is made and thrown away?

- Why aren’t plastics as cheap as they seem?

- What is plastic pollution?

- How does plastic pollution harm everyone?

- Who is disproportionately harmed by plastics?

- What can you do to fight against plastic pollution?

How are plastic products made?

Plastic production begins with fossil fuel extraction; these fossil fuels are then refined and processed into petrochemicals. Petrochemicals are used to create different types of plastics with specific properties. Manufacturers shape these plastics into everyday products, often adding other chemicals to make them stronger, more flexible, or colorful.

How do plastics drive fossil fuel demand?

As the energy sector shifts to renewables, the fossil fuel industry has turned toward plastics as a way of maintaining demand for their planet-harming products.4,5 The International Energy Agency has predicted that petrochemicals, which are used to make plastics, will soon become the largest driver of global oil demand.6

How much plastic is made and thrown away?

Global plastic production was over 470 million tons in 2019.1 This is more than the weight of all the humans alive today.8 And annual production is projected to double by 2050.1 Industry is on track to create more plastics in the next 25 years than have been produced in the history of the world so far.1,a

When they think of plastics, people often think of packaging—and, indeed, packaging makes up a significant 31% of all plastics’ use. But the building and construction sector is the second-biggest contributor, responsible for 17% of global plastics production. From PVC pipes to nylon carpet and vinyl siding, tens of millions of tons of plastics are used in construction each year.10 Other major uses include transportation, textiles, consumer and institutional products, and electrical/electronic equipment and devices.

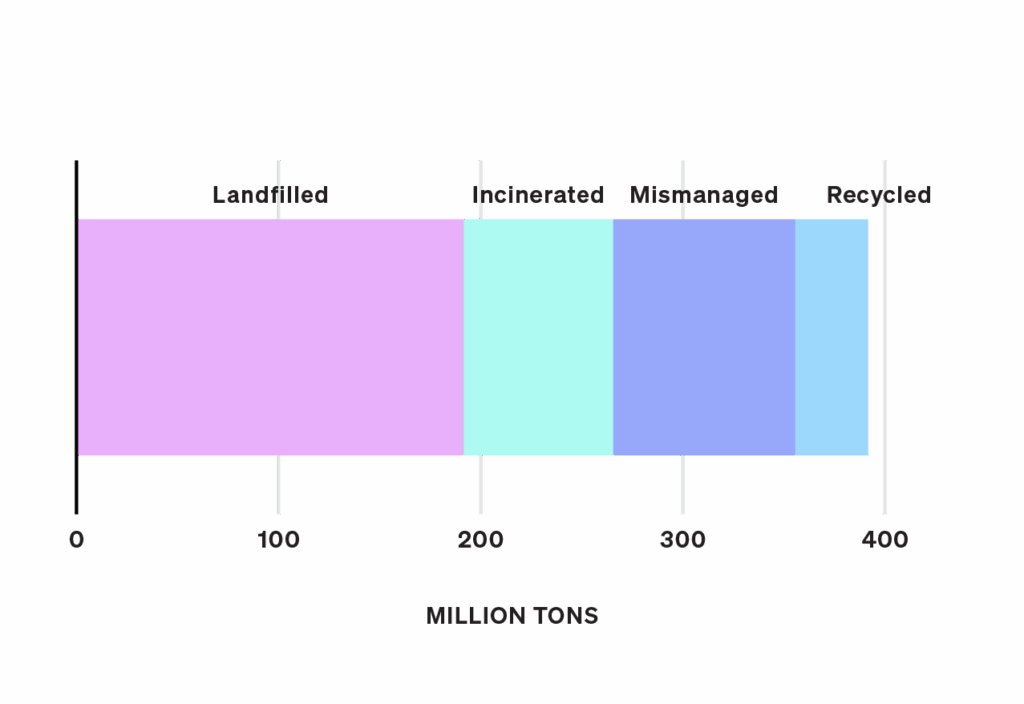

Plastics last a long time and do not biodegrade, which translates to a lot of plastic waste.11 Humankind generated about 390 million tons of plastic waste in 2019,1 and this amount is projected to almost triple by 2060, reaching over 1.1 billion tons per year.9 The vast majority of plastic waste is landfilled, incinerated, or mismanaged (disposed of in uncontrolled dump sites, burned in open uncontrolled fires, or leaked to the environment where it builds up in ecosystems on land and in waterways).1,12 For example, international estimates project that by 2060, there could be a staggering 543 million tons of plastic accumulated in aquatic environments, including 160 million tons in the ocean.9

Why aren’t plastics as cheap as they seem?

While many plastic materials appear inexpensive, the price tag excludes substantial societal costs of harm to human health and the environment.13

Annually, production of plastics causes an estimated $592 billion in health harms globally.14,b A small subset of plastic-related chemicals generates an estimated $249 billion in medical and associated social costs every year in the U.S. alone.15 Plastic pollution is estimated to result in $100 billion of environmental damage every year.13 And these are conservative estimates.c Reducing plastics use can lead to major health and economic benefits.

The costs of climate change, too, are immense. Global warming increases the frequency of extreme weather events, each causing billions in damage. The U.S. faced 27 separate billion-dollar weather and climate disasters in 2024 alone—nearly matching the record-setting 28 events in 2023. These disasters resulted in over $182 billion in damages that year.16 Plastic production contributes to these mounting costs.

Government subsidies hide the real cost of plastics, with annual global subsidies totaling $7 trillion for fossil fuels and on the order of $30 billion for plastic production in the top 15 producing countries.17,18 A similar pattern exists at the local level. The Environmental Integrity Project reviewed 50 plastic plants built or expanded in the U.S. since 2012 and found that 32 of these plants received almost $9 billion in state and local tax breaks and taxpayer subsidies. Two-thirds of the more than 591,000 people living within three miles of the 50 new or expanded plants are people of color, revealing how environmental burdens often fall disproportionately on communities of color.19

These costs are paid by individuals and governments, not fossil fuel or plastic companies.14

What is plastic pollution?

The United Nations defines plastic pollution as “the negative effects and emissions resulting from the production and consumption of plastic materials and products across their entire life cycle.”13 Plastics generate pollution at every stage of their life, from fossil fuel extraction, through manufacturing, use, and disposal. This pollution—including greenhouse gases, microplastics, and toxic chemicals—harms everyone.

How does plastic pollution harm everyone?

Widespread pollution generated across the plastic life cycle is harming people and Earth’s ecosystems.12,20 Sometimes this pollution is readily apparent: smoke plumes or smells from a factory or plastic bottles in the gutter. Whether we can see or smell it or not, plastic pollution affects all of us—through greenhouse gas emissions; through the microplastic particles and toxic chemicals that make their way into our bodies from air, water, and food; and through impacts on the health of people and our planet. For example:

Climate change

Plastics contribute to climate change at every stage of their life cycle. Greenhouse gases are released during fossil fuel extraction, refining, and transportation. Plastic manufacturing processes emit additional climate pollutants. Even after use, plastic products continue damaging the climate as they degrade or burn in incinerators.21 Plastic production alone is responsible for over 5% of global greenhouse gas emissions and continues to grow.22

Microplastics

While plastics don’t biodegrade, they do break down into small and tiny particles known as micro- and nanoplastics. These particles range from about the size of an orange seed to the width of a strand of DNA, and they are everywhere.23 We are exposed to them through the food we eat, the water we drink, and the air we breathe. Microplastics have been found throughout human bodies, including our blood, kidneys, hearts, brains, and more, and there is evidence they build up over time.24–27 Project TENDR, an alliance of experts on toxic chemicals and brain development, notes that, “[b]abies today are born with their brains and bodies already contaminated with plastics. Micro- and nano-plastic particles have been found in the placenta and newborns’ first stool, with exposures continuing through breastmilk and infant formula.”28 Scientists are only just starting to learn how microplastics harm the health of children and adults, but research suggests they contribute to a range of adverse outcomes, such as cancer and infertility.29

Microplastics from paint?!

Did you know most paint is made with plastic? Researchers estimate that paint—including architectural, marine, road marking, general industrial, automotive, and industrial wood paint—is the largest source of microplastic leakage into oceans and waterways, accounting for 58% of known sources. A third of paint used in the architectural sector each year will eventually end up in the environment (oceans, waterways, and land), including an estimated 4 million tons of plastic.30

Toxic Chemicals

In addition to plastics themselves being a health concern as described above, plastics also use and release toxic chemicals throughout their life cycle. These chemicals are used throughout plastics production—extraction and refining of fossil fuels and production of chemicals, plastics, and products. In addition to “regular” releases of toxic chemicals that occur during production, each life cycle step and transportation of chemicals for each process also creates risk of fires, explosions, spills, and leaks.31 More than 16,000 different chemicals may be used to make, or are present in, plastics. Over 25% of these are known to be hazardous to human health or the environment, and most others lack information on their safety. This includes thousands of chemicals that are intentionally added to plastics to impart particular properties, such as making them more flexible, durable, or colorful.32 Chemicals used to create plastics pollute our air, water, soil, and bodies and have been linked to cancer, reproductive issues, children’s developmental harm, asthma, obesity, and many more health impacts.14,33–36

Human Health Impacts

Workers, communities, and users of plastic products face direct exposure to these harmful substances. Additionally, chemical wastes from plastic production and most plastic products themselves are landfilled or incinerated, burdening communities with additional pollution.1,14,34,37 Even recycling can release microplastics and toxic chemicals that affect human health.38,39

Environmental Impacts

Beyond local contamination, many plastic chemicals as well as microplastics spread globally through air and water, disrupting ecosystems and contaminating environments worldwide.1,32,36 Landfilling and incineration of plastic waste further burdens the environment with persistent pollution, while recycling processes can also release environmental contaminants.14,32,38,39

Who is disproportionately harmed by plastics?

While we are all harmed by plastic pollution, some of us are harmed more than others.

Children are especially vulnerable to chemical exposures. Beginning in the womb and continuing into adolescence, their cells and bodies are in a dynamic state of growth.40 Chemical exposures have many damaging effects. They can interrupt hormone systems and inhibit healthy brain development. Scientists suspect chemical exposures have contributed to the increased rates of childhood cancers like leukemia and neurodevelopmental disorders like ADHD present today.28,40,41 Exposure to toxic chemicals early in life can continue to harm health years later through effects such as reduced fertility and increased risk of obesity, asthma, and cancer.41

Communities near polluting facilities (chemical plants, landfills, incinerators, etc.) are directly affected by noise, odors, chemical emissions, and heavy duty diesel emissions.42–44 Such “fenceline” communities are disproportionately communities of color, Indigenous communities, and low-wealth communities.14,42,45 Often, industrial facilities are concentrated in “sacrifice zones” such as Louisiana’s Cancer Alley. This 85-mile stretch of communities along the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge is home to about 200 fossil fuel and petrochemical facilities. Residents of the area suffer from elevated rates and risks of reproductive, maternal, and newborn health harms; cancer; and respiratory ailments such as asthma.46 Hear directly from Cancer Alley residents in this video from Human Rights Watch.

Plastic chemicals and microplastics travel through air and ocean currents, concentrating in the Arctic and disproportionately affecting the land, water, and traditional foods of Arctic Indigenous communities.36,47 Climate change is also greater in Arctic regions which are warming almost four times faster than the planet as a whole. The health of these communities is threatened by the toxic impacts of the fossil fuel and plastics industry in addition to climate-induced threats to food security and community displacement.36

What can you do to fight against plastic pollution?

From the vinyl flooring under our feet to the polyester in our clothing, plastics surround us in ways we’re only beginning to fully understand. The evidence is clear: these ubiquitous materials are driving climate change, contaminating our bodies with chemicals and microplastics, and releasing toxic chemicals that disproportionately harm children, communities of color, Indigenous communities, and low-wealth communities. The hidden costs reveal the true price of our plastic dependency.

Here are four concrete steps you can take right now to meaningfully reduce plastic use while protecting people and the environment:

- Minimize new material use and reuse existing products when possible

- Choose healthier materials when new products are necessary

- Choose long-lived, timeless materials that remain in place for their full service life

- Evaluate recycling claims critically, as recycling often perpetuates rather than reduces plastics’ harmful life cycle impacts

The same innovation that created this challenge can solve it. As sustainability professionals, we have the knowledge, networks, and influence to accelerate the transition already underway.

Endnotes

- OECD Global Plastics Outlook projects total plastic production 2025-2049 to be 16,285 million tonnes. Plastic production from 1950-2024 is estimated to total 12,193 million tonnes. Limited data is available for plastic production prior to 1950, but even assuming 1950 levels of production in each of the prior 15 years only marginally increases the total plastic production to date.

- All costs are in US dollars.

- Scarcity of data means that these estimates do not include a full accounting of cost, but they provide a general idea of the monumental and costly scale of impact.

Bibliography

- OECD. Global Plastics Outlook: Economic Drivers, Environmental Impacts and Policy Options; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, 2022. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/environment/global-plastics-outlook_de747aef-en (accessed 2024-09-09).

- Plastics Europe. History of plastics. https://plasticseurope.org/plastics-explained/history-of-plastics/ (accessed 2025-01-23).

- Reckoning with the U.S. Role in Global Ocean Plastic Waste; National Academies Press: Washington, D.C., 2022. https://doi.org/10.17226/26132.

- Center for International Environmental Law. Fueling Plastics: Untested Assumptions and Unanswered Questions in the Plastics Boom, 2018. https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Fueling-Plastics-Untested-Assumptions-and-Unanswered-Questions-in-the-Plastics-Boom.pdf.

- Salzman, A. Plastic is Everywhere. Now Big Oil Companies Are Producing Even More of It. Barrons. https://www.barrons.com/articles/shell-chevron-oil-chemicals-plastics-d75f8fee (accessed 2025-01-29).

- International Energy Agency. The Future of Petrochemicals: Towards More Sustainable Plastics and Fertilisers; 2018. https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-petrochemicals (accessed 2023-05-17).

- Guterres, A. X (formerly Twitter). https://twitter.com/antonioguterres/status/1598667368296751109?lang=en.

- Greenspoon, L.; Krieger, E.; Sender, R.; Rosenberg, Y.; Bar-On, Y. M.; Moran, U.; Antman, T.; Meiri, S.; Roll, U.; Noor, E.; Milo, R. The Global Biomass of Wild Mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120 (10), e2204892120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2204892120.

- OECD. Global Plastics Outlook: Policy Scenarios to 2060; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, 2022. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/environment/global-plastics-outlook_aa1edf33-en (accessed 2024-07-26).

- OECD. Global Plastics Outlook: Plastics Use by Application, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1787/234a9f22-en.

- Babaremu, K. O.; Okoya, S. A.; Hughes, E.; Tijani, B.; Teidi, D.; Akpan, A.; Igwe, J.; Karera, S.; Oyinlola, M.; Akinlabi, E. T. Sustainable Plastic Waste Management in a Circular Economy. Heliyon 2022, 8 (7), e09984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09984.

- Villarrubia-Gómez, P.; Almroth, B. C.; Eriksen, M.; Ryberg, M.; Cornell, S. E. Plastics Pollution Exacerbates the Impacts of All Planetary Boundaries. One Earth 2024, 7 (12), 2119–2138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2024.10.017.

- United Nations Environment Programme. Turning off the Tap: How the World Can End Plastic Pollution and Create a Circular Economy; Nairobi, 2023. https://www.unep.org/resources/turning-off-tap-end-plastic-pollution-create-circular-economy (accessed 2024-10-31).

- Landrigan, P. J.; Raps, H.; Cropper, M.; Bald, C.; Brunner, M.; Canonizado, E. M.; Charles, D.; Chiles, T. C.; Donohue, M. J.; Enck, J.; Fenichel, P.; Fleming, L. E.; Ferrier-Pages, C.; Fordham, R.; Gozt, A.; Griffin, C.; Hahn, M. E.; Haryanto, B.; Hixson, R.; Ianelli, H.; James, B. D.; Kumar, P.; Laborde, A.; Law, K. L.; Martin, K.; Mu, J.; Mulders, Y.; Mustapha, A.; Niu, J.; Pahl, S.; Park, Y.; Pedrotti, M.-L.; Pitt, J. A.; Ruchirawat, M.; Seewoo, B. J.; Spring, M.; Stegeman, J. J.; Suk, W.; Symeonides, C.; Takada, H.; Thompson, R. C.; Vicini, A.; Wang, Z.; Whitman, E.; Wirth, D.; Wolff, M.; Yousuf, A. K.; Dunlop, S. The Minderoo-Monaco Commission on Plastics and Human Health. Ann. Glob. Health 2023, 89 (1), 23. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.4056.

- Trasande, L.; Krithivasan, R.; Park, K.; Obsekov, V.; Belliveau, M. Chemicals Used in Plastic Materials: An Estimate of the Attributable Disease Burden and Costs in the United States. J. Endocr. Soc. 2024, 8 (2). https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvad163.

- Smith, A. 2024: An active year of U.S. billion-dollar weather and climate disasters | NOAA Climate.gov. Beyond the Data. http://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2024-active-year-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters (accessed 2025-01-29).

- International Monetary Fund. Climate Change: Fossil Fuel Subsidies. https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/climate-change/energy-subsidies (accessed 2024-11-04).

- Eunomia; QUNO. Plastic Money: Turning Off the Subsidies Tap; Phase 1 Report; Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. https://quno.org/timeline/2024/8/new-report-plastic-money-turning-subsidies-tap-phase-1 (accessed 2024-08-26).

- Environmental Integrity Project. Feeding the Plastics Industrial Complex; 2024. https://environmentalintegrity.org/reports/feeding-the-plastics-industrial-complex/ (accessed 2024-07-02).

- Teresa McGrath; Rebecca Stamm; Veena Singla; Bethanie Carney Almroth. Buildings’ Hidden Plastic Problem: Policy Brief and Recommendations; Habitable, 2024. https://habitablefuture.org/resources/constructions-hidden-plastic-problem-policy-brief-and-recommendations/ (accessed 2024-11-25).

- Hamilton, L. A.; Felt, S.; Muffett, C.; Kelso, M.; Malone Rubright, S.; Bernhardt, C.; Schaeffer, E.; Moon, D.; Morris, J.; Labbe-Bellas, R. Plastic & Climate: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet, 2019. https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Plastic-and-Climate-FINAL-2019.pdf.

- Karali, N.; Khanna, N.; Shah, N. Climate Impact of Primary Plastic Production; LBNL-2001585; Sustainable Energy and Environmental Systems Energy Analysis and Environment Impacts Division Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 2024. https://eta-publications.lbl.gov/sites/default/files/climate_and_plastic_report_final.pdf.

- Breathing Plastic: The Health Impacts of Invisible Plastics in the Air. Center for International Environmental Law. https://www.ciel.org/breathing-plastic-the-health-impacts-of-invisible-plastics-in-the-air/ (accessed 2024-12-20).

- Balch, B. Microplastics are inside us all. What does that mean for our health?. AAMC. https://www.aamc.org/news/microplastics-are-inside-us-all-what-does-mean-our-health (accessed 2024-12-11).

- Dutchen, S. Microplastics Everywhere. Harvard Medicine Magazine. Spring 2023. https://magazine.hms.harvard.edu/articles/microplastics-everywhere (accessed 2024-12-11).

- Nihart, A. J.; Garcia, M. A.; El Hayek, E.; Liu, R.; Olewine, M.; Kingston, J. D.; Castillo, E. F.; Gullapalli, R. R.; Howard, T.; Bleske, B.; Scott, J.; Gonzalez-Estrella, J.; Gross, J. M.; Spilde, M.; Adolphi, N. L.; Gallego, D. F.; Jarrell, H. S.; Dvorscak, G.; Zuluaga-Ruiz, M. E.; West, A. B.; Campen, M. J. Bioaccumulation of Microplastics in Decedent Human Brains. Nat. Med. 2025, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03453-1.

- Chartres, N.; Cooper, C. B.; Bland, G.; Pelch, K. E.; Gandhi, S. A.; BakenRa, A.; Woodruff, T. J. Effects of Microplastic Exposure on Human Digestive, Reproductive, and Respiratory Health: A Rapid Systematic Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c09524.

- Project TENDR. Project TENDR Briefing Paper: Protecting the Developing Brains of Children from Plastics and Toxic Chemicals in Plastics; 2024. https://www.akaction.org/publications/project-tendr-plastics-briefing-paper/ (accessed 2024-07-19).

- Colliver, V. Microplastics in the Air May Be Leading to Lung and Colon Cancers. University of California San Francisco. December 18, 2024. https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2024/12/429161/microplastics-air-may-be-leading-lung-and-colon-cancers (accessed 2024-12-20).

- Paruta, P.; Pucino, M.; Boucher, J. Plastic Paints the Environment; EA – Environmental Action, 2022. https://www.e-a.earth/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/plastic-paint-the-environment.pdf (accessed 2024-01-03).

- Azoulay, D.; Villa, P.; Arellano, Y.; Gordon, M.; Moon, D.; Miller, K.; Thompson, K. Plastic & Health: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet; 2019. https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Plastic-and-Health-The-Hidden-Costs-of-a-Plastic-Planet-February-2019.pdf (accessed 2023-12-08).

- Wagner, M.; Monclús, L.; Arp, H. P. H.; Groh, K. J.; Løseth, M. E.; Muncke, J.; Wang, Z.; Wolf, R.; Zimmermann, L. State of the Science on Plastic Chemicals – Identifying and Addressing Chemicals and Polymers of Concern; 2024. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10701706.

- Habitable. Pharos Common Products, 2025. https://pharos.habitablefuture.org/common-products.

- HBN/EEFA/NRDC. Chemical and Environmental Justice Impacts in the Life Cycle of Building Insulation: Case Study on Isocyanates in Spray Polyurethane Foam; Energy Efficiency for All, 2022. https://informed.habitablefuture.org/resources/research/18-case-study-on-isocyanates-in-spray-polyurethane-foam.

- Seewoo, B. J.; Wong, E. V. S.; Mulders, Y. R.; Goodes, L. M.; Eroglu, E.; Brunner, M.; Gozt, A.; Toshniwal, P.; Symeonides, C.; Dunlop, S. A. Impacts Associated with the Plastic Polymers Polycarbonate, Polystyrene, Polyvinyl Chloride, and Polybutadiene across Their Life Cycle: A Review. Heliyon 2024, 10 (12), e32912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e32912.

- Miller, P.; Karlsson, T.; Medina, S. S.; Waghiyi, V. The Arctic’s Plastic Crisis: Toxic Threats to Health, Human Rights, and Indigenous Lands from the Petrochemical Industry, 2024. https://www.akaction.org/wp-content/uploads/ipen-alaska_report-2024-final-compressed.pdf.

- Toxic-Free Future; Material Research L3C. PVC Poison Plastic: An Investigation Following the Ohio Train Derailment of Widespread Vinyl Chloride Pollution Caused by PVC Production; 2023. https://toxicfreefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Report-PDF-PVC-Poison-Plastic-Investigation-4.pdf.

- Hahladakis, J. N.; Velis, C. A.; Weber, R.; Iacovidou, E.; Purnell, P. An Overview of Chemical Additives Present in Plastics: Migration, Release, Fate and Environmental Impact during Their Use, Disposal and Recycling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 179–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.10.014.

- Stapleton, M. J.; Ansari, A. J.; Ahmed, A.; Hai, F. I. Evaluating the Generation of Microplastics from an Unlikely Source: The Unintentional Consequence of the Current Plastic Recycling Process. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 166090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166090.

- US EPA. NIEHS/EPA Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research Centers Impact Report: Protecting Children’s Health Where They Live, Learn, and Play; EPA Publication No. EPA/600/R-17/407; 2017. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2017-10/documents/niehs_epa_childrens_centers_impact_report_2017_0.pdf.

- The Consortium for Children’s Environmental Health. Manufactured Chemicals and Children’s Health — The Need for New Law. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392 (3), 299–305. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMms2409092.

- Environmental Justice Health Alliance and Coming Clean. Life at the Fenceline: Understanding Cumulative Health Hazards in Environmental Justice Communities; 2018. https://ej4all.org/life-at-the-fenceline (accessed 2022-06-24).

- CleanAirNow. CleanAirNow Environmental Justice Recommendations:Comments on the Armourdale General Plan, 2021. https://ucs-documents.s3.amazonaws.com/misc/armourdale-general-plan.pdf.

- The Climate Reality Project. Let’s Talk about Sacrifice Zones. https://www.climaterealityproject.org/blog/lets-talk-about-sacrifice-zones (accessed 2022-06-24).

- Johnston, J.; Cushing, L. Chemical Exposures, Health and Environmental Justice in Communities Living on the Fenceline of Industry. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2020, 7 (1), 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-020-00263-8.

- Human Rights Watch. “We’re Dying Here” The Fight for Life in Louisiana Fossil Fuel Sacrifice Zone; 2024. https://www.hrw.org/report/2024/01/25/were-dying-here/fight-life-louisiana-fossil-fuel-sacrifice-zone (accessed 2025-01-24).

- Bergmann, M.; Collard, F.; Fabres, J.; Gabrielsen, G. W.; Provencher, J. F.; Rochman, C. M.; van Sebille, E.; Tekman, M. B. Plastic Pollution in the Arctic. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3 (5), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-022-00279-8.

As sustainability professionals, we face a sobering reality: every day, materials are extracted, manufactured, used, and discarded at a rate that outpaces the Earth’s ability to regenerate.1

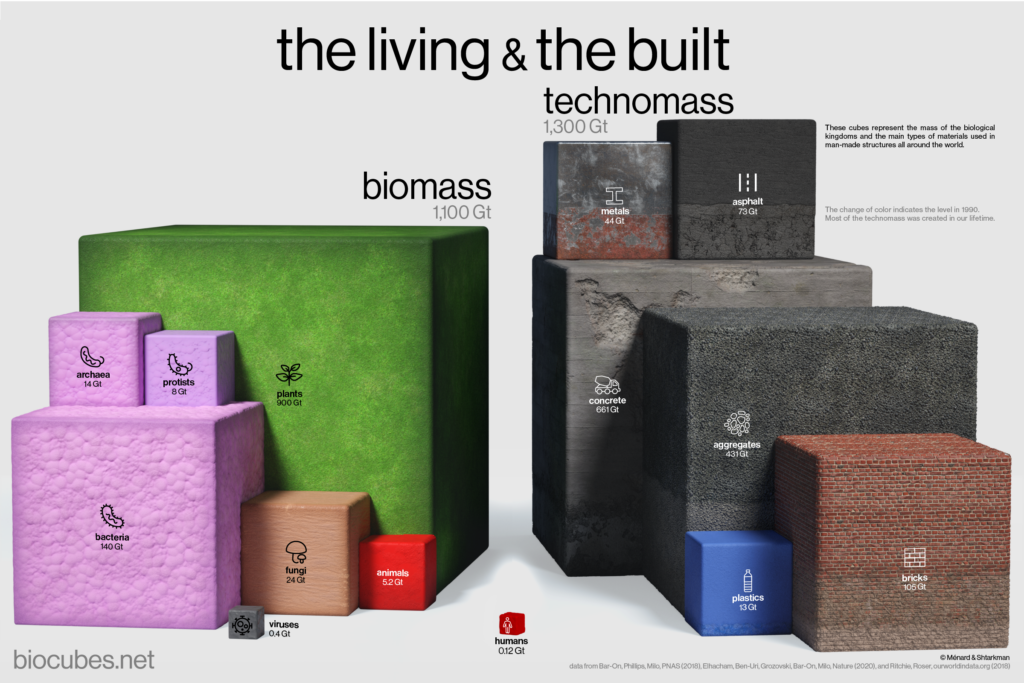

Our global ecological footprint has reached unprecedented levels.2 Humanity’s total material demand–our buildings, roads, machines, and products–now outweighs all living things on Earth.3 These aren’t just statistics, they are a wake-up call for everyone working in sustainability and materials management.

I’ve spent the last two decades working on climate impact and waste assessment for companies and governments across the United States, and have watched as local sustainability efforts have flourished while the global environmental picture becomes more and more grim. One of the biggest challenges I’ve seen is that the traditional metrics of sustainability–carbon footprints, waste reduction targets, efficiency gains–are designed to drive localized, regional progress. These measures of ‘success’ overlook a crucial reality: when we cut costs and resource use in one place, consumption often increases somewhere else in the world. As sustainability professionals leading the charge for a more just and regenerative future, our biggest challenge today is not merely advancing existing measures of ‘success.’ Instead, we must fundamentally reimagine our relationship with an economic system that prioritizes growth above all else and shift toward one that values health through balance and harmony with nature. When the planet is healthy, we are healthy.

This reality is pushing sustainability leaders to ask harder questions: How can we create genuine prosperity while respecting Earth’s ecological limits? What would it look like to build a materials economy that serves both people and planet? The answers require us to examine not just how we manage materials, but how we think about growth itself.

The Limits We Face

There is already a great body of knowledge on “the ability to thrive as a society, while respecting biophysical limits.”4 This wisdom, however, stems from ways of living and being that do not center economic size as a marker of societal well-being. In contrast, the goal of most economies around the world today is to simply grow.

The Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy recently showed that the world’s seven largest economies have enshrined “economic growth” as a goal in and of itself, detached from any kind of social or well-being metrics.5 But economic growth doesn’t happen in a vacuum: our environment, people, and communities are all impacted by macroeconomic decisions. Considering this, three key issues emerge that challenge our perception of growth’s ‘success’:

- First, there are ecological constraints. The global economy must operate within Earth’s ecological limits – thresholds for resource extraction, land use, and pollution that we are currently exceeding. We simply cannot sustain current levels of ecological demand.

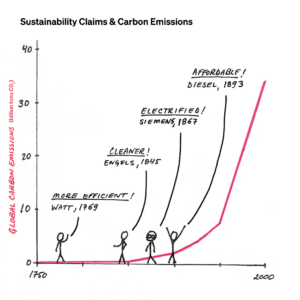

- Second, there are efficiency limitations. Our current materials economy is deeply interconnected: when one company reduces its material use, the saved resources are typically invested into other parts of the economy, driving further growth and consumption. Time and experience have proven that efficiency gains do not actually reduce resource use, unless they are paired with a commitment to limit demand.6

- Finally, there are equity concerns. The benefits and burdens of our materials economy are not shared equally. While ~10% of global society controls 90% of the wealth,7 billions still lack access to basic resources for a dignified life.,8,9 Shifting our economy towards alternative and more efficient technologies alone will not address this fundamental imbalance.

Let’s dive a little deeper into how these issues affect people and our planet:

Earth’s Limited Resources

We must acknowledge and work within Earth’s limits to economic growth. Our collective ecological demands have been outpacing the regenerative capacity of our planet since the 1970s.10 Globally, we’ll need to shrink the total size of that demand in order to bring our footprint back in balance with nature.

Humans’ fossil-fueled economy has pushed the global climate past its natural limits: recent highly visible weather events related to our changing climate are symptomatic of pushing past ecological constraints. This isn’t unique to climate–all natural systems have boundaries and it is now time for us to work within the boundaries of a healthy, thriving planet.

Beyond the Efficiency Trap

Efficiency gains must be coupled with limits on total ecological demand. To date, the most common approach for reducing ecological demand has been introducing more efficient technologies: new power plants, more fuel-efficient engines, and ever-smaller computing devices deliver their services with less material input per unit of output. But when we reduce resource use through efficiency, a growth-focused economy uses those saved resources to consume more elsewhere. It’s like squeezing a balloon – the air just moves to a different spot.

The factors that drive ecological change on planet earth are connected to commodity flows that operate across political boundaries, meaning reduced demand in one part of the economy is easily offset by increased consumption in another. For example, the U.S. has reduced its fossil fuel demand over the past two decades, but the global economy has easily reallocated those savings in the planetary push for economic growth. In practice, efficiency gains are often redirected into making more products, feeding a cycle of continuous growth that ultimately leads to more extraction, more waste, and more strain on our planet’s systems.

Illustration by John Mulrow, PhD

Centering Equity

Sustainability strategies must prioritize equity alongside environmental goals. Our traditional, Western understanding of economic growth prioritizes gain for a small subset of the global population. Even if economic growth were intended to benefit all humanity, it has failed in practice.

In his book Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World, Jason Hickel presents data showing that while global GDP per capita increased fivefold between 1980-2016, this growth was highly unequal, with only the wealthiest 10% of people seeing their incomes grow at or above this rate. The richest 1% gained disproportionately more, while the vast majority of people experienced minimal economic benefits despite overall growth.11 This pattern repeats even within high-income countries, as Matt Orsagh, a post-growth finance advocate, has pointed out. In the US, it is also the wealthiest 10% of people that have accumulated the majority of economic growth for themselves in recent decades.12 Clearly, there is a need to rebalance and redefine economic flows so that when and where growth happens it benefits those truly in need.

New Metrics for a Healthy, Thriving Planet

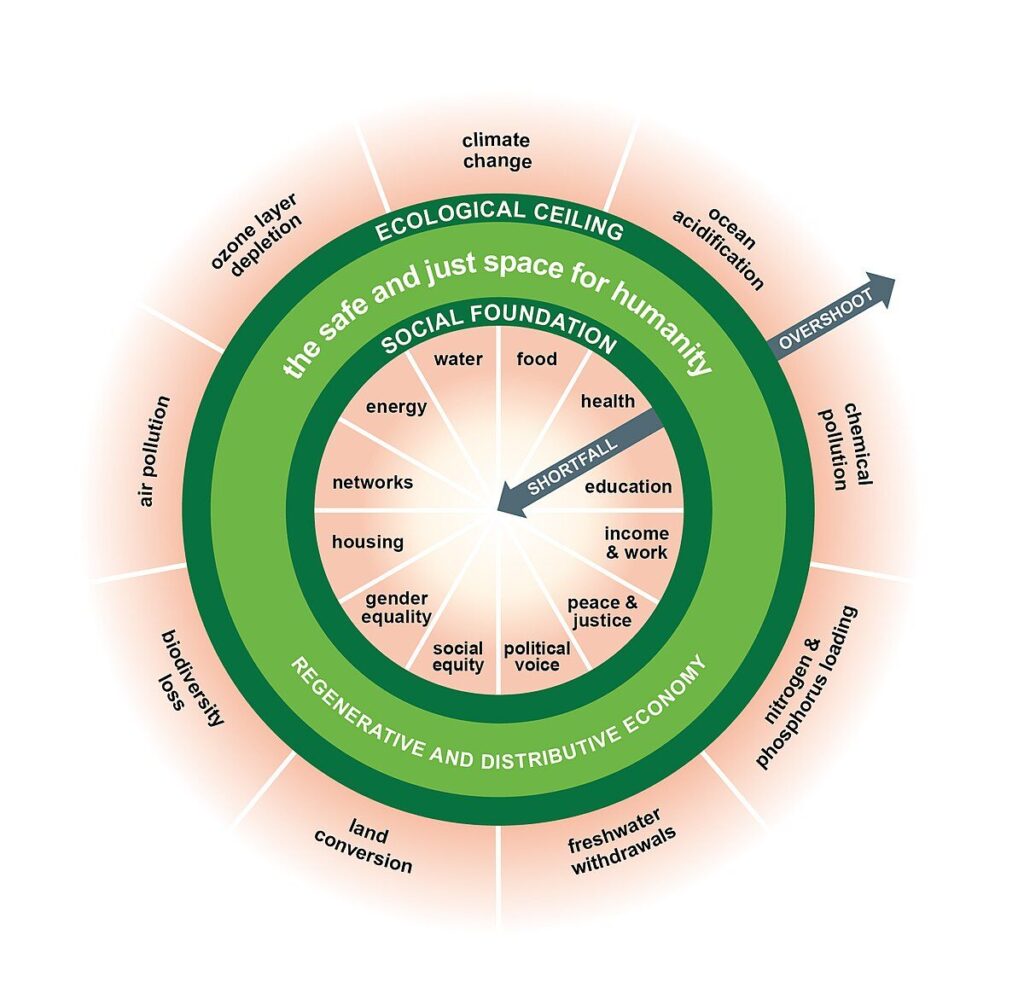

Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics concept has provided a framework for seeking social and environmental sustainability without prioritizing growth for growth’s sake. The doughnut diagram represents a safe and just operating space for humanity, with the inner boundary representing minimum requirements for human well-being (the social foundation), and the outer boundary representing planetary systems impacted by economic activity (ecological ceiling).

The reality is that social foundation metrics are not being met for many across the world and yet we are exceeding planetary boundaries, atmospheric CO2 levels being just one of several ecological emergencies. Raworth’s work has been effective at helping sustainability professionals break from efficiency as a marker of environmental impact reduction, instead pairing planetary-scale impact metrics with socioeconomic ones like equity and access.

Well-Being

New ways of thinking about growth bring fresh focus to the fundamental question of what truly constitutes ‘wealth’ versus ‘well-being.’ While social and ecological metrics provide important global context, numbers alone won’t be enough to persuade a critical mass of environmental advocates and professionals to break from the commitment to growth embedded in most sustainability plans.

To orient away from growth, we’ll need enticing ways to live the good life with less economic throughput. That’s why this reimagining of economics prompts psychological inquiries into the question “how much is enough?”, explorations of indigenous ways of knowing and being, and long-standing critiques of economic development goals aimed at increasing Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as the sole marker of societal well-being.

A Future Beyond Growth

As a sustainability professional on this journey, I constantly remind myself that the path beyond growth is still being trodden. It extends from many places in humanity’s past, and the justifications for redefining growth are not solely technical; ongoing ecological degradation is not in need of ever-more refined climate, energy, and economic forecasting techniques. Economic growth is a social and political commitment embedded in daily life. Challenging it necessitates action in both personal and professional spheres.

Here are some steps to begin:

- Foster Dialogue: Sometimes asking questions like “How much is enough?” or “How can we use less?” are enough to spark a conversation that questions the growth paradigm in a constructive way. You can share and build on writings that critique growth–influential works like Doughnut Economics by Kate Raworth, Less is More by Jason Hickel, and Braiding Sweetgrass and The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer provide valuable perspectives. The Degrowth Institute’s discussion toolkit also offers practical resources for sparking conversations.

- Integrate Global Contexts: Add a global economic perspective to your projects. For example, consider what happens to financial and resource savings enabled by efficiency measures. Can these savings be reinvested in ways that increase equity or protect the environment, instead of prompting more consumption? What are the risks that resource demand resurfaces elsewhere in the economy? Asking such questions can shift the focus toward systemic change.

- Stay Motivated: Breaking from growth-centric paradigms is crucial for self-regulating our economy within planetary boundaries. Although unprecedented in modern times, this shift promises significant social and environmental benefits and recent summaries in Ecological Economics offer concrete policy proposals.

For those based in the U.S., various organizations—including the Post Growth Institute, CASSE, Arketa Institute, and DegrowNYC—are advancing the movement through discussion, debate, and action.

Sustainability’s next great challenge is to build a smaller, fairer economy that ensures a thriving future for all within the limits of our one shared planet.

Remember, the goal isn’t perfection—it’s progress toward a materials economy that works for both people and planet. Each step we take builds momentum for broader change. The transition to balance our ecological footprint won’t be easy, but it’s essential for a shared future. As sustainability professionals, we have the opportunity–and responsibility–to lead this transformation. By taking these concrete steps within our organizations, we can help create a future where innovation serves the goal of true sustainability rather than limitless growth.

About the Author

John Mulrow, PhD

John Mulrow is Executive Director of the Degrowth Institute and Adjunct Assistant Professor of Environmental and Ecological Engineering at Purdue University. His work is focused on improving environmental assessment methodology through perspectives that prioritize social equity and limits to growth. He holds a PhD in Civil Engineering from University of Illinois Chicago and a BS in Earth Systems from Stanford University.

DEFINITIONS

Ecological footprint: Economic goods and services require inputs that originate from natural systems

Ecological resources include raw materials such as water, fuels, plants, and mineral ores and natural functions such as water flow, photosynthesis, and atmospheric circulation.

Ecological demand is the ecological footprint required to meet human wants and needs.

Ecological constraints are the limits of demand, beyond which certain natural systems become destabilized. These limits can be characterized in many ways but we prefer the Stockholm Resilience Institute’s planetary boundaries framework.

FOOTNOTES

- https://footprint.info.yorku.ca/data/

- https://footprint.info.yorku.ca/data/

- biocubes.net

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/exploring-environmental-violence/degrowth-perspective-on-environmental-violence/561C3D8FA140F8EB1EFCE6EDBEE8A46E

- https://steadystate.org/the-economic-priority-of-the-seven-wealthiest-countries-more-wealth/

- See “Banking sustainable consumption’s savings” in https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388491654_Degrowth_and_Sustainable_Consumption

- https://www.credit-suisse.com/media/assets/corporate/docs/about-us/research/publications/global-wealth-databook-2022.pdf

- https://www.activesustainability.com/environment/natural-resources-deficit/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2542519624000421

- https://footprint.info.yorku.ca/data/

- Hickel, J. (2022). Less is more: How degrowth will save the world. Penguin Books.

- Orsagh, M. (2024, December 16). Degrowth is the Answer | Substack. https://degrowthistheanswer.substack.com/

Habitable’s policy brief, “Buildings’ Hidden Plastic Problem,” reveals stunning statistics about current and projected plastic use in buildings and includes recommendations to reduce plastic pollution—greenhouse gases (GHGs), microplastics, and toxic chemicals—throughout product life cycles.

This policy brief presents highlights from the significant body of science indicating that plastic building materials are contributing to serious health and environmental harms over their life cycle, from fossil fuel extraction to production, use, and disposal. These impacts fall disproportionately on susceptible and marginalized people, including women, children, Indigenous people, low-income communities, and people of color. The brief includes examples of solutions and offers recommendations to strengthen policies that will reduce plastic use in the built environment and associated life cycle harms.

Endorsing organizations:

- Alliance of Nurses for Healthy Environments

- Alaska Community Action on Toxics

- American Sustainable Business Network

- Between the Waters

- Beyond Plastics

- Cannon Design

- Changing Materials/Changing Streams

- Children’s Environmental Health Network

- Cooper Carry

- Defend Our Health

- Earthjustice

- Ecology Center

- Green Science Policy Inst

- Healthy Babies Bright Futures

- Just Zero

- Little Things Matter

- Moms Clean Air Force

- MSR Design

- Planetary Health Alliance

- Plastic Free Future

- Plastic Pollution Coalition

- Safer States

- Science and Environmental Health Network

- Toxic Free Future

Interested in endorsing these policy recommendations? Contact us.

French—lire en français

Spanish—leer en español

English—read in english

This fact sheet highlights the building and construction sector’s significant contributions to global plastic pollution.

Using case studies of flooring products specified in the K-12, healthcare, and affordable housing sectors, the fact sheet introduces opportunities for building practitioners to reduce the plastic footprint of their buildings and emphasizes the impact that one building can make by specifying low/no-plastic products.

Habitable’s report, “Advancing Health and Equity through Better Building Products,” reveals the current state of building materials used, with nearly 70% of typical products in the categories analyzed containing or relying on the most hazardous chemicals.

The results, based on data for Minnesota affordable housing, are consistent with products used in other building types and geographic regions. The report highlights examples of leaders within and beyond Minnesota’s built environment who are already taking action toward safer material choices. It also provides guidance on how the real estate industry can begin working toward a healthier future by “stepping up from red-ranked products”—the most polluting and harmful throughout their life cycle based on Habitable’s research and Informed™ product guidance.

A path towards planetary health is more urgently needed now than ever, but our current materials economy creates rampant pollution, climate change, and growing inequity. Shifting from harmful practices to healthful solutions will require cross-sector partnerships, holistic thinking, and exciting new approaches that reduce the burden of industry on people and our planet.

Watch Habitable’s special Earth Month webinar featuring leading global voices, including:

- Dr. Bethanie Carney-Almroth

- Dr. Veena Singla

- Martha Lewis

Moderated by Gina Ciganik, CEO of Habitable

HBN tested 94 commercially available paint products for the presence of harmful per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), called “forever chemicals”. Approximately 50% of paints tested positive for fluorine, a marker of PFAS. Review the details of our findings and the recommended actions you can take.

Pollution

Pollution Climate Change

Climate Change Health

Health

Equity

Equity