Policy Brief + Recommendations

Policy Brief + Recommendations

Habitable’s policy brief, “Buildings’ Hidden Plastic Problem,” reveals stunning statistics about current and projected plastic use in buildings and includes recommendations to reduce plastic pollution—greenhouse gases (GHGs), microplastics, and toxic chemicals—throughout product life cycles.

This policy brief presents highlights from the significant body of science indicating that plastic building materials are contributing to serious health and environmental harms over their life cycle, from fossil fuel extraction to production, use, and disposal. These impacts fall disproportionately on susceptible and marginalized people, including women, children, Indigenous people, low-income communities, and people of color. The brief includes examples of solutions and offers recommendations to strengthen policies that will reduce plastic use in the built environment and associated life cycle harms.

Endorsing organizations:

- Alliance of Nurses for Healthy Environments

- Alaska Community Action on Toxics

- American Sustainable Business Network

- Between the Waters

- Beyond Plastics

- Cannon Design

- Changing Materials/Changing Streams

- Children’s Environmental Health Network

- Cooper Carry

- Defend Our Health

- Earthjustice

- Ecology Center

- Green Science Policy Inst

- Healthy Babies Bright Futures

- Just Zero

- Little Things Matter

- Moms Clean Air Force

- MSR Design

- Planetary Health Alliance

- Plastic Free Future

- Plastic Pollution Coalition

- Safer States

- Science and Environmental Health Network

- Toxic Free Future

Interested in endorsing these policy recommendations? Contact us.

French—lire en français

Spanish—leer en español

English—read in english

This fact sheet highlights the building and construction sector’s significant contributions to global plastic pollution.

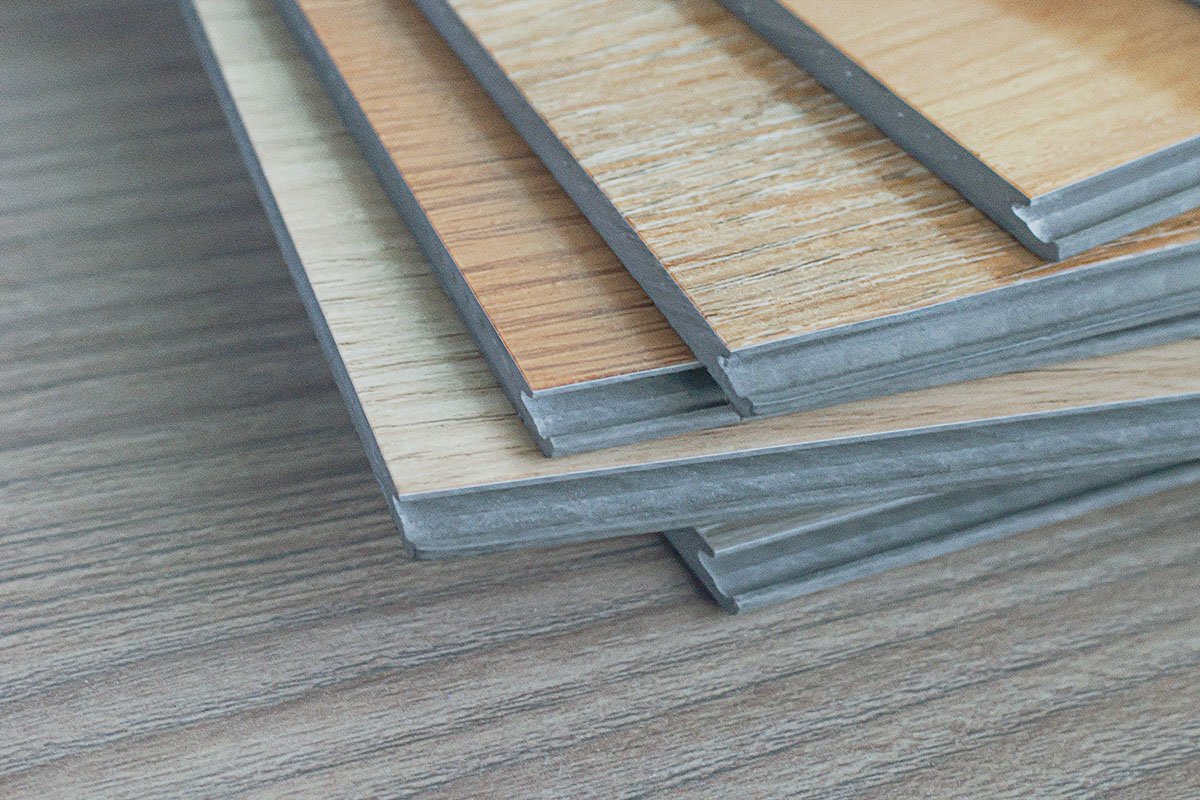

Using case studies of flooring products specified in the K-12, healthcare, and affordable housing sectors, the fact sheet introduces opportunities for building practitioners to reduce the plastic footprint of their buildings and emphasizes the impact that one building can make by specifying low/no-plastic products.

Explore the critical role of value engineering (VE) in plumbing systems with this comprehensive report, “Value Engineering in Plumbing Systems.” Discover how effective VE can optimize costs without compromising essential functions, while understanding the potential pitfalls through real-world examples like the costly Baltimore hotel case.

Learn from the insights of industry professionals who emphasize the importance of balancing cost with durability, safety, and sustainability. This report provides essential guidance for architects, engineers, and contractors on making informed decisions to maintain plumbing system integrity and avoid costly mistakes. Download the report today to enhance your approach to VE in plumbing projects.

NBC’s Cynthia McFadden interviews an expert from Toxic Free Future about their recent report revealing that over 36 million pounds of vinyl chloride are transported daily on more than 200 rail cars, highlighting the risks similar to those seen in the East Palestine train derailment.

This report discusses concerns about replacing lead service lines with PVC plastic pipes, highlighting the potential health and environmental risks associated with leaching chemicals, urging for thorough consideration and evaluation of alternative piping materials.

We have been picking on plastics a lot recently (see articles: Addressing the Plastic Crisis: Why Vinyl Has to Go and The Illusion of Plastic Recycling: Neither Just Nor Circular). This is because we believe that typically the best way to avoid hazardous chemicals is to avoid plastic altogether. With this said, we recognize plastics in buildings are currently ubiquitous (see article: Our Plastic Buildings: A New Driver of Fossil Fuel Demand).

So, let’s consider what would need to happen for plastic building products to be considered truly sustainable. Can the plastics industry do better? What are the key opportunities today to do so, and what global policy tools could promote these opportunities? These are among the key questions HBN explored in the development of a pair of case studies for the international Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as part of the Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC).

Before we jump into the case study findings, first, let’s define plastics. For the purposes of this article, we define plastics to be any polymeric material, fossil fuel based or bio-based. The case studies focused on durable plastic goods, using building materials as an example.

The case studies explored both plastic flooring and plastic insulation with the goal of increasing awareness of environmental and human health impacts of plastic product production at each stage of the lifecycle and proposing policy interventions that can help move the industry toward more sustainable plastics products in general.

What would be defined as a sustainable plastic?

In the report, we created a framework for evaluating what a truly sustainable plastic product would look like. These goals are lofty, and currently no existing plastic building materials meet these goals. However, they provide a pathway towards truly sustainable products.

To be considered a sustainable plastic, a product would have to enhance human and environmental health and safety across the entire product life cycle. It would have to be managed within a sustainable materials management system, and would have to meet the following goals:

- Must be inherently low hazard.

- Hazardous substances are eliminated.

- Transparency in terms of content and emissions exists at every step of the supply chain.

- Full hazard assessments are available on all chemicals.

- Must have a confirmed commercial afterlife.

- Products designed for durability, reclamation, reuse, and recycling.

- Infrastructure exists to support reclamation, reuse, and recycling.

- Materials can undergo multiple cycles of recycling.

- Must generate no waste.

- Manufacturing scrap is eliminated at every step of the production process.

- Scrap from installation is eliminated.

- Must use rapidly renewable resources or waste-derived materials.

Trade-offs examples

The case study explores trade-offs that exist between different material choices.

For a flooring example, a product that is designed to use adhesive to install is typically thinner than one that uses a click tile system to install. These thinner products use less material per square foot and therefore have less chemical impacts associated with manufacturing and less waste at the end of life. However, adhesives may add hazardous substances to the product installation stage. By moving from a click tile product to a glue down product, chemical exposure burdens shift from manufacturing and end of life to the installation stage and use phase.

For an insulation example, a product that is designed to chemically react at the build site, such as spray polyurethane foam (SPF), can allow the insulation to form an air-sealed custom fit. However, SPF is not recyclable, and adherence of that insulation to surrounding materials may also make those materials more difficult to reclaim or recycle. Moving from XPS, EPS or polyiso to SPF may reduce the ability of other surrounding materials to “have a commercial afterlife” in the pursuit of an added performance feature.

Building awareness around these trade-offs enables stakeholders to make informed choices.

Back to reality

Now, back to reality after crafting the characteristics of a theoretical sustainable plastic. The bottom line is that there are no sustainable plastics that exist today, and we are a long way off from that day. Today, project teams need to prioritize which sustainability goals are most important and how to deal with real and significant gaps in understanding and/or data.

The case studies compared only product types made of plastic, but in reality, project teams have a wider variety of materials to choose from in any given product category. HBN’s Product Guidance considers the most commonly used product types within a product category and ranks those product types relative to one another from a chemical hazard perspective. Product types made of plant-based materials or minerals tend to rank higher than plastic products. You can apply the same sustainability goals proposed in this article to non-plastic products.

In project design, the biggest leaps towards more sustainable products from a chemicals perspective often requires consideration of vastly different materials versus making incremental improvements in chemistry for a particular product type. For example, this could mean moving from vinyl to linoleum flooring versus attempting to select the least bad vinyl option.

Check out the full flooring and insulation case studies for examples of how to use these goals to consider and choose the variety of plastic product types you will inevitably be specifying for your next project. Alternatively, challenge yourself to skip the plastics whenever possible. Even selecting one non-plastic product is cause for celebration. Make the swap!

What do building materials have to do with social justice? Learn more in this article by Diana Alley, Avideh Haghighi, and Lona Rerickat at ZGF Architects.

Health Care Without Harm Europe advocates for the complete elimination of PVC due to its environmental impact, urging policymakers to develop a strategy for its phase-out in Europe.

If we are to have any chance of addressing the global plastics crisis, Polyvinyl Chloride plastic (PVC) also known as vinyl, has got to go.

It cannot be produced sustainably or equitably. It cannot be “optimized.” It cannot be recycled. It will never find a place in a circular economy, and it makes it harder to achieve circularity with other materials, including other plastics.

There are three reasons for this: technical, economic, and behavioral. The inherent qualities of PVC and its cousin, CPVC, make it among the most technologically challenging plastics to recycle. Like most plastics, PVC is made with fossil fuel feedstocks. Unlike other plastics, PVC/vinyl also contains substantial amounts of chlorine, upwards of 40%. This is the C in PVC, and this chlorine content adds an additional layer of negative impacts to the earth and its people, social inequity, and an impediment to recycling that cannot be overcome. Recyclers consider it a contaminant to other plastic feedstock streams.1 It mucks up the machines and the already perilous economics of plastics recycling.

There is an emerging global consensus on this point, albeit euphemistically stated. The Ellen MacArthur New Plastics Economy Project consists of representatives from the world’s largest plastic makers and users, along with governments, academics, and NGOs. In 2017 it reached the conclusion that PVC was an “uncommon” plastic that was unlikely to be recycled and should be avoided in favor of other more recyclable packaging materials.2 “Uncommon” in the diplomatic parlance of international multistakeholder initiatives means unrecyclable. The project also took note of the many toxic emissions associated with PVC production.

That’s not surprising since after 30 years of hollow promises and pilot projects doomed to fail, virtually no post-consumer PVC is recycled.3 Conversely, leading brands with forward-looking materials policies such such as Nike, Apple, and Google have prioritized PVC phase outs.4

But in the building industry, PVC rages on. Virgin vinyl LVT flooring is the fastest growing product in the flooring sector. So much so that in 2017 sustainability leader Interface introduced a new product line of virgin vinyl LVT, despite forecasting just one year before that by 2020 the company would “source 95 percent of its materials from recycled or biobased resources.”5

The current flooring market demands the impossible – aesthetic qualities and durability at a price unmatchable by non-vinyl floor coverings. A price that is unmatchable because at every stage of vinyl production, the societal costs of its poisonous environmental health consequences are externalized, subsidized, paid for by the people who live in communities that have become virtual poster children for environmental injustice and oppression. Places like Mossville, LA; Freeport, TX; and the Xinjiang Province in China, home to the oppressed Uighur population. As we detail in our exhaustive Chlorine and Building Materials report, the unique chlorine component of PVC plastic contributes to a range of toxic pollution problems starting with the fact that chlorine production relies upon either mercury-, asbestos-, or PFAS-based processes. This is in addition to the onerous environmental health burdens of petrochemical processing that burden all plastics.

It is true that all plastics contribute to environmental injustices. Virtually all plastics are made from fossil fuel feedstocks, and all plastics share abysmally low recovery and cycling rates. Still, independent experts agree that some plastics are worse than others, and PVC is among the worst.6 Additionally, most uses of PVC have readily available alternatives or solutions that are within reach. Certainly there are non-PVC alternatives for flooring. What can’t be beat is the cost – that is, the low purchase price at the point of sale, subsidized by the sacrifices we ignore in the communities where the plastics are manufactured and the waste is dealt with. And BIPOC communities bear the disproportionate burden of it all. Acknowledging and addressing this tradeoff is at the root of the behavioral change that stands between us and a just and healthy circular economy.

In his influential book How To Be An Antiracist, Dr. Ibram X. Kendi argues that if we recognize we live in a society with many racial inequities – and acknowledge that since no racial group is inferior or superior to another, the cause of these inequities are policies and practices – then to be anti-racist is to challenge those policies and practices where we can and create new ones that create equity and justice for all.

Imagine if as part of our commitment to equity in our sustainability efforts, we recognized, acknowledged, and did what we could to address the racial inequities associated with PVC production, and committed right now to stop using PVC unless it was absolutely essential. The plastics industry would howl and point out inconsistencies, question priorities, highlight unintended consequences. We would all feel a tinge of whataboutism – what about carbon, or this other injustice, or that shortcoming of the alternatives. But it is clear that widespread incrementalism is failing us on so many fronts, none more than the environmental injustices that are hardwired into our supply chains.

In fact, there are many examples of companies and building projects that have prioritized PVC-free alternatives based upon principles of equity and justice. We need more leaders in the field to join those who are abandoning vinyl in product types that have superior options. Our CEO Gina Ciganik used a non-PVC flooring in 2015 at The Rose, her last development project prior to joining HBN.

First Community Housing, another affordable housing leader, has been using linoleum for many years for similar reasons. In their Leigh Avenue Apartments project. Forbo’s Marmoleum Click tiles were the flooring of choice.

Vinyl is not an essential material for any of the largest surface areas of our building projects – flooring, wall coverings, or roofing. It may often be the conventional choice in conventional buildings, but it should not be the conventional choice in buildings that promise to be green, healthy, and equitable. LVT may be the fastest growing flooring product in the world, but it is a throwback to the inequitable, unsustainable world we say is unacceptable, not the world we are trying to create.

Habitable can help you start by using our Informed™ product guidance, which helps identify worst and best in class products that are healthier for people and the planet. So why not start here and now, with a principled stand of refusing to profit from unjust, frequently racist, externalized costs?

SOURCES

- https://plasticsrecycling.org/pvc-design-guidance

- See pp. 27-29: www.newplasticseconomy.org/assets/doc/New-Plastics-Economy_Catalysing-Action_13-1-17.pdf

- See e.g. Figure 1: https://css.umich.edu/publication/plastics-us-toward-material-flow-characterization-production-markets-and-end-life

- See e.g.: www.apple.com/environment/answers (Apple); www.greenpeace.org/usa/reports/greener-electronics-2017 (Google); www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-aug-26-fi-16540-story.html (Nike)

- www.greenbiz.com/article/inside-interfaces-bold-new-mission-achieve-climate-take-back: “Going Beyond Zero” The march towards Mission Zero continued unabated, however, with consistent year-over-year improvement in most metrics. Today, the company forecasts that by 2020 it will halve its energy use, power 87 percent of its operations with renewable energy, cut water intake by 90 percent, reduce greenhouse gas emissions 95 percent (and its overall carbon footprint by 80 percent), send nothing to landfills, and source 95 percent of its materials from recycled or biobased resources.

- www.cleanproduction.org/resources/entry/plastics-scorecard-press-release

Phase 2 of this report is the first of its kind plant-by-plant accounting of the production, use, and releases of chlorine and related pollution around the world. It is intended to inform the efforts of building product manufacturers to reduce pollution in their supply chains.

Chlorine is a key feedstock for a wide range of chemicals and consumer products, and the major ingredient of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic. The report includes details aboutthe production technologies used and markets served by 146 chlor-alkali plants (60 in Asia) and which of these plants supply chlorine to 113 PVC plants (52 in Asia). The report answers fundamental questions like:

- Who is producing chlorine?

- Who is producing PVC?

- Where? How much? And with what technologies?

- What products use the chlorine made in each plant?

Key findings include:

- Over half of the world’s chlorine is consumed in the production of PVC. In China, we estimate that 74 percent of chlorine is used to make PVC.

- 94 percent of plants in Asia covered in this report use PFAS-coated membrane technology to generate chlorine.

- In Asia the PVC industry has traded one form of mercury use for another. While use of mercury cell in chlorine production is declining, the use of mercury catalysts in PVC production via the acetylene route is on the rise. 63 percent of PVC plants in Asia use the acetylene route.

- 100 percent of the PVC supply chain depends upon at least one form of toxic technology. These include mercury cells, diaphragms coated with asbestos, or membranes coated with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), used in chlorine production. In PVC production, especially in China, toxic technologies include the use of mercury catalysts.

Supplemental Documents:

Pollution

Pollution Health

Health Equity

Equity